|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

|

|

|

|

Revised excerpt of a compilation by Dr. Ulla Johansen, „Die Ornamentik der Jakuten“, published in German in 1954

by the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology as an ethnological signpost; it is out of print today. |

|

|

Below you can see great examples - click on an icon (text) - Enjoy!

© Albi - Face Music 2012

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

|

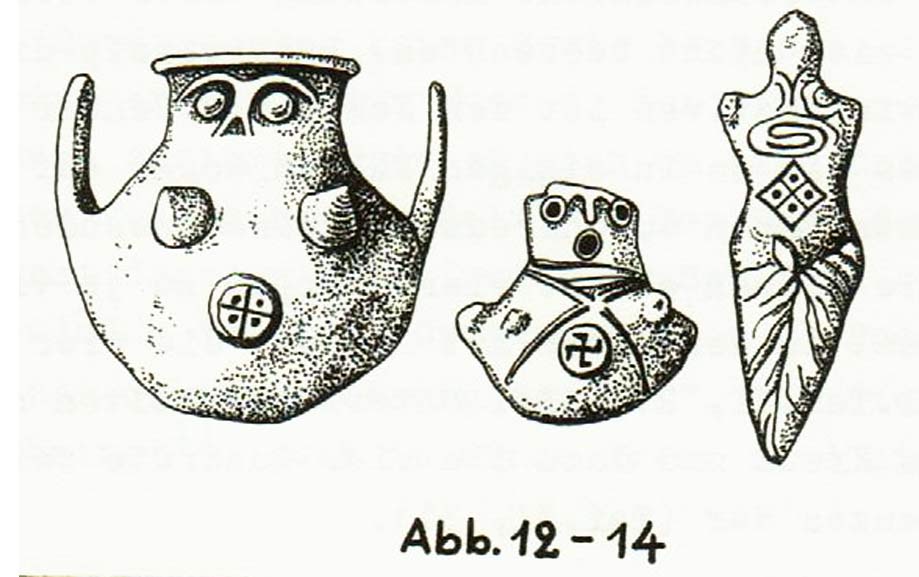

Many motives like this appear among finds from pre-Christian epochs of Siberian history (2000 to 3000 BC). Objects of the same kind were found that were manufactured using a similar technique. Thus, derivations seem possible.

Comparable pre-historic finds that came to the surface around Lake Baikal propably belonged to the Yakuts’ ancestors, the Quryqan (Ruan Ruan – Juan Juan), who settled at the same time as the Hsiung-nu in the Altai area. Remains of ceramics are particularly telling. The ornaments are applied to pots in the same way or a similar way using the same technique. These motives include the triangle, the zigzag pattern, the crest pattern and the arch ornament imprinted with fingernails. Regarding their shape and ornament, the Yakut kumis cups can be compared with so-called “Scythian kettles” from the epoch of the animal style, which are attributed to the Tagar and Pazyryk periods at the Yenisei (900 to 200 BC) and which also belong to the culture of the European Huns (the Black Huns). In the middle of the 1st millennium AD, this container was still used by the Kyrgyz, by the 5th to 9th millennium AC only in the Southern Altai.

|

- Hsiung-nu – Xiongnu – 3rd century BC to 4th century AD

- Find more information, including information about these Altai tribes, on - Hsiung-nu - Xiongnu

- Skythes (Sakas – Sarmatians – Massagetae): 8th to 3rd centuries AD

- Tagar culture from the 9th to the 6th centuries AD

- Pazyryk culture from the 6th to the 2nd centuries AD

- more information on the tribes see “History of the Equestrian Nomads“

|

The ornaments are mostly composed of geometric motives. The meaning they used to have is hard to determine today. However, there is no doubt the decorations had a connection to something, which suggests a religious origin.

|

The Yakuts

The largest portion is covered by taiga, but the tree population thins noticably towards the north and finally gives way to treeless tundra in the outermost east and north. In the southern territories, people conduct agriculture and partly animal husbandry. The animals used to be horses and cattle; and in the very north, there is some reindeer breeding as well. Resources found for processing in craftwork were wood and animal products, bog iron, fireclay, and silver brought in via coins.The Yakuts, a Turkic people, live in the contemporary independent Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in far Eastern Siberia. Its territory extends from the south via the area around the Aldan river and the Central Siberian highland in the West, beyond the river Lena, across the Verkhojansk Range and the Chersky Range to the Kolyma Lowland in the northeast and finally the polar sea. The Yakuts’ living conditions are extraordinarily hard, as the growing season in their area lasts for a very short part of the year. During no more than 60 to 100 days they enjoy a short summer with temperatures above 5 degrees Celsius, which places their land, with the exception of a very small area in the south, in the zone of eternally frozen ground (permafrost).

In one of their legends, the Yakuts say that their creator, when he had made the Earth, sent a messenger over Siberia with a bag full of riches. When the messenger flew over the territory at the northern polar circle, his fingers stiffened, and he dropped everything. Riches like gold, silver and platinum landed on Earth. Irate about his loss, the creator is said to have punished this region with eternal winter. |

|

The immigration of the Yakuts into the Lena valley was among the last migrations of Turkic tribes from Central Asia. Unlike the other Turkic peoples, the Yakuts did not follow routes to the south or west but migrated to the northeast. Their movement began in the 12th century, and it lead them from the southern region of Lake Baikal in a northern direction, at a time when the Mongolian clans were just about to extend their sphere of control beyond the Altai. Their initial settlements are believed to have been at the upper Yenisei, as their craftwork has many parallels to the tribes there. Common life with other peoples already resident here did not always come easy. The Yakuts settled mainly on humid and fertile planes of the large Lena and Aldan arch, at the river Vilyui, and at the affluents of these major rivers. In the north, they first focussed on the humid, accessible river valleys. The indigenous Tungusic people (Evenks, Evens) were forced to retreat to the mountains, where they could still survive, as they almost exclusevily fed on reindeer breeding, just like remaining Yukaghirs in this territory, who are almost entirely extinct today. They are one of the oldest and today also the smallest people in this area. They settled here in the northeast as early as the Neolithic Era. The Taiga Yukaghirs at the upper section of the Kolyma river and the Tundra Yukaghirs north of the Polar Circle lived as reindeer breeders and hunters of fur-bearing animals.

Later, during the Iron Age, the Evens, followed by the Evenks, progressed into this area. Both are Tungusic peoples, and both were initially nomads. Up north, they bred reindeer and hunted fur-bearing animals. However, note that these areas were retreats these minorities were forced into by the heavily propagative Yakuts. Legends of the Yakuts and the Tungusic people involve fights that supposedly took place. Many of these peoples have been entirely “Yakutized” by today, like the Tungusic Dolgans. All Tungusic people had to retreat into the higher mountainous areas during the past two centuries, where they live together in peace today.

|

|

|

- Uralic group – Ugric people: Khants (Khantys), Mansis, Samoyedes (Nenets, Enets, Nganasans) and Yukaghirs

- Altaic group – Turkic: Yakuts (Sakha), Tuvinians, Khakas, Altaians (Oirates, Teleutes, Telengites),

Uyghurs, Mongolic and Tungusic people (Evenks - Evens)

- Paleosiberien group: Ainu, Koryaks, Itelmens (Kamchatkan), Chukchee (Tshuktshen)

|

|

- Work with the Aboriginal peoples of Siberia following - currently under construction!

|

New-age archeological finds show parallels between the Yakuts and the Buryats and Altaians. Although their vocabulary indicates earlier ethnological research, affiliation with the Tungusic (Evenkic) group is easier to back up. During the 14th century, a large part of them was “Turkized”. Today, the Yakut language is classified as a Turkic language. Comparison between the mitochondrial DNA of Yakuts and that of other Eurasian peoples shows high accordance with the Evenks, who partly settled in the same area, and the Turkic-speaking Tuvinians who live in Southern Siberia at the upper Yenisei river. The Yakut society was traditionally composed of the nobility (leaders), free citizens, and slaves. They lived as hunters, fishermen and, to a much smaller extent, as peasants, reindeer or horse breeders.

Ever since the period prior to World War II the population has shifted very much in favor of the Russians. Digging for the vast abundance of gold in the areas at the upper section of Kolyma river and in the areas of the rivers Aldan, Vitim and Patoma lured many workers into the region. This recent development does not have to be taken into consideration when talking about ornaments, as their materials are from earlier periods. However, for a better understanding of the Yakuts’ ornaments, their world view of earlier times has to be described, where many motives and symbols originate.

|

The cosmos as a whole is divided into an upper, a lower, and a middle world, the latter being inhabited by humans. In the upper world, which they imagine to have seven celestial layers, the white lord creator “Ürüng Ajy Tojon” resides, who is also simply called “Tangara”, sky or sky god. The underworld, on the other hand, is dominated by “Arsan Duolai”. The other spirits live in the middle or lower world, which are not separated by an exact line. A moral judgement on good or evil and eternal revenge were alien to the Yakut mind. Also, the spirits of the individual planes did not have any relationship to one another but they each ruled as independent lords in their respective territory. This can be compared to the animism of other peoples. Animism means nature having a soul and also includes certain practices of shamanism and curing. In this we can find parallels with Turkic peoples in the Sayan Altai Mountains and the Mongolians, as well as in the ornaments. Ever since pre-Christian times, culture is based on a dualism of Father Sky and Mother Earth, which is hardly different from the Chinese principle of Yin and Yang. Ying equals the Earth, while Yang corresponds to the sky.

|

- Find further information on the religion of the indigenous peoples of Siberia as well as on shamanism at: Religion of the indigenous people of Siberia und Shamanism (Tengerism) in Mongolia

|

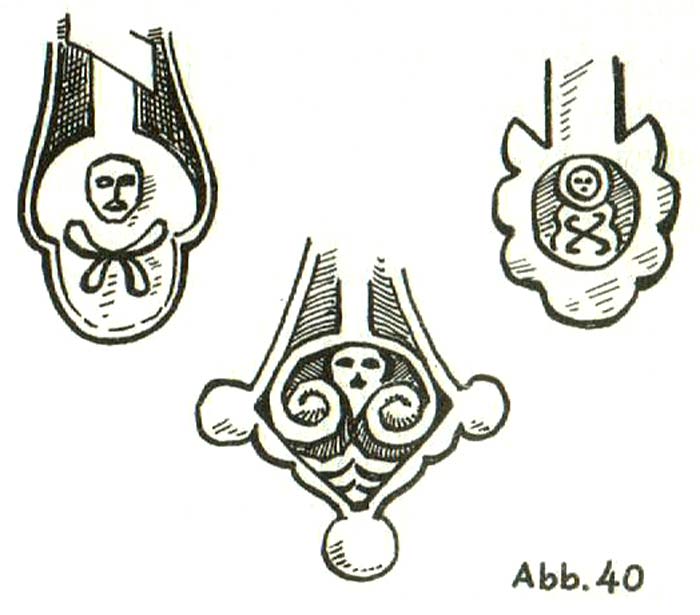

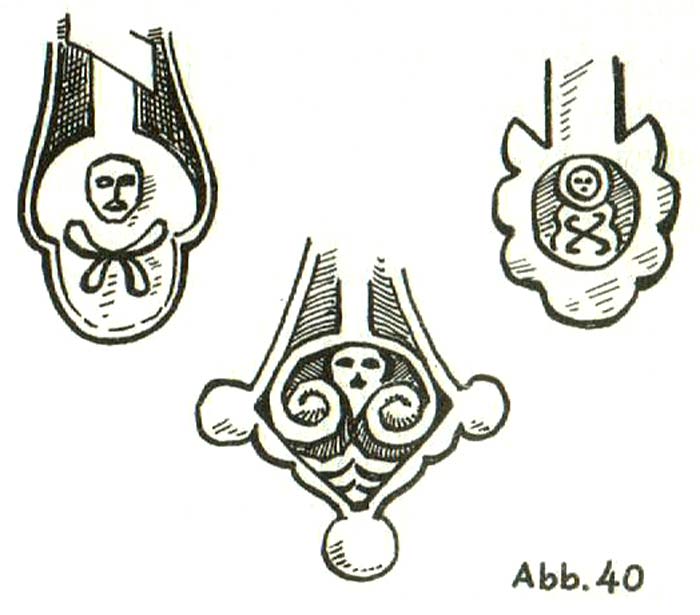

The religion of the Yakuts has retained its animist world view. The Yakuts imagine nature, and partly the objects in it, to be inhabited by a soul, an owning spirit whose rights have to be respected. To insult this spirit would have the most terrible consequences. They were called “iggi” or “ongon” = spirit’s dwelling. They may live in rivers, on mountains, or in a blacksmith’s tools, or maybe in the fermented mare’s milk called “kumis”. People offer horse’s hair to the spirit of the mountains or the spirit of fire, while a small grey man is offered some drops of butter. Two spirits (souls) live in one person, one of which causes the procedures of the body, the other those of the mind. Following death, the latter turns into the spirit of death. In order to protect oneself from his persecution, people carve human-shaped figurines out of wood, then the shaman places the soul of the dead inside them by magic, and they are packed into a little birchbark bag. This bag is suspended in a corner of the house, and offerings are made to it. Very often, the shape of a former female shaman, “Makyny-Kysa-Tynyraxtax Kagai”, who turned into a kind of fury when she died, is depicted. It is carved from wood and clad in fur. Even if a shaman has placed her spirit into this doll, it is still dangerous to touch this idol, which is usually placed on the mantle above the fireplace. The wrath of this being who shall not be named, the wrath of “Kys-Tangara” the “virgin goddess”, could break out and do evil. The Yakuts say that the spirit that resides in every object shows itself via the shadow it casts.

The shamans act as mediators between these spiritual beings and humans. They cure their diseases, negotiate on the sin offering and perform the respective ritual. They are responsible for the balance of and compliance with all the rituals within the family or society. Totemism manifested itself in the belief that the shaman retains animal spirits who help him during his visits at the spirits’ dominions, in particular birds. Shamans are also protectors of certain individual families. Also, the shaman is accompanied by other, invisible animal spirits, such as a bull, stallion, bear, elk, or eagle, and he has to die together with them. Not all shamans were equally powerful and capable of communicating with all spirits. Those with a horse totem were considered the most powerful because apart from the eagle the horse was viewed as the noblest of animals. An earlier subdivision into black shamans for chthonic spirits (dark spirits who live underneath the earth) and white shamans for the beings of the sky no longer applies.

This religiosity accounts for the fact that the Yakuts avoided any kind of biomorphic representation (live, biomorphic shapes in sculpturing) in their art, in sculptures and drawings as well as in ornaments. Any realistic human or animal shape was capable of coming to life as an evil demon that would turn against its creator or its environment. Realistically shaped animals attached to the shamans’ clothes constituted an exception, as they were considered actually alive. Even toy cows were represented schematically and non-realistically, without legs, a tail or a head, so they could not be instantly identifed as cows. The Yakuts lacked the ability of drawing by nature. Still, it is amazing how simple their drawings appear compared to their highly developed ornaments.

|

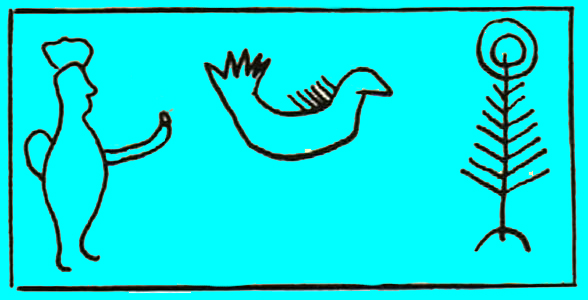

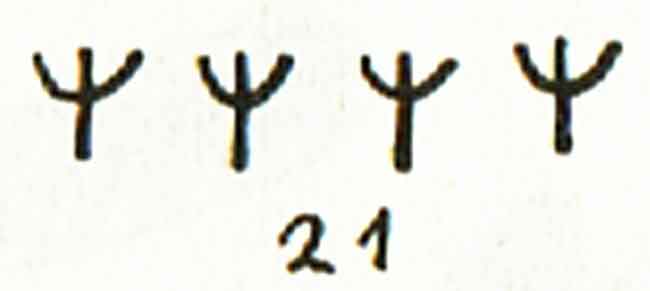

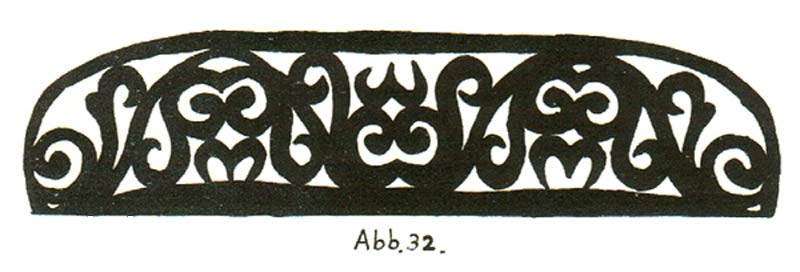

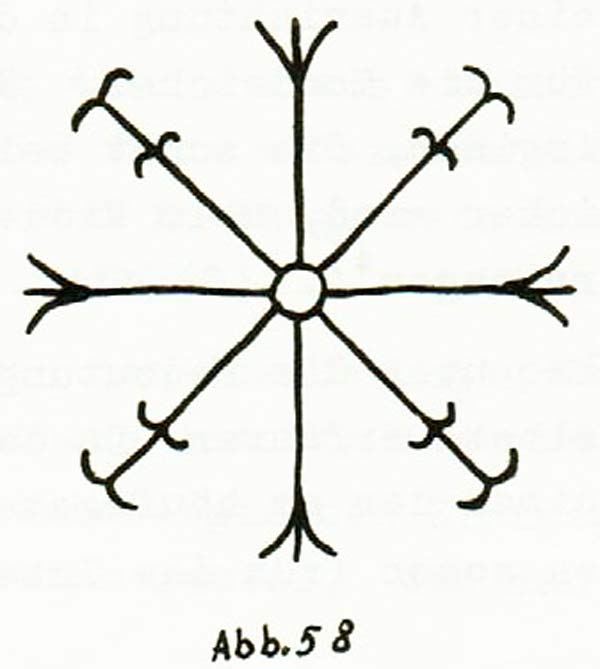

| Note this depiction of a drawing of a shaman and his bird next to a seven-branched birch, which the Yakuts considered a ladder to heaven. |

|

|

The Yakuts were alien to realistic representation, even in decorative art.

However, they were fond of harmonious, evenly shaped, entirely abstract ornaments, which appeared to them to be the highest form of art. In this field, the Yakuts achieved absolute perfection. They felt an extraordinary need for symmetry, which is also found in other Siberian peoples. Still, only Paleosiberian peoples, like the Eskimos and Kets, produced rather vivid drawings at the Yenisei, but those are not of interest here.

|

- Kets (Keto) – Self-designation “ket” (“human”) or “deng” (“people”); historical designation: Yenisei Ostyaks – they speak a Paleosiberian language.

|

Objects designed of mammoth ivory in the New Age bearing figurative representations can therefore definitely be considered non-authentic. Apart from these products there were no other figures that served profane, unhallowed purposes.

Language: The Yakuts are the northernmost Turkic speaking people. They are referred to as Turkic because the construction of their language and their vocabulary equal a very old form of Turkish while part of it has Mongolian origins and incorporates Tungusic, Samoyedic, and Yukaghir expressions or expressions of entirely unknown origin. Their subsistence strategy as horse breeders seems as unusual as their language because to breed horses was not customary among their Tungusic and Paleosiberian neighbors.

Origin: The fact that the Yakuts immigrated from the South has never been doubted. They were forced into the Lena area from the Baikal region. This was irrevocably confirmed only by excavations showing extensive matches between pottery products of the population that inhabited this area until the end of the 1st millennium and Yakut products. The Yakut ornaments are part of a Sayan-Baikal-Lena art circle, which is expressly distinct from the art of the neighboring peoples. Differences are most significant in spiral and plant ornaments. Their migration into this northern area is believed to have happened in a time prior to the Mongolian expansion because in the Buryat folklore, many memories of Genghis Khan have remained, which the Yakuts had never heard of. The first historical information of the Buryats progressing to the Baikal region is in fact from the 12th century AD, which means, it was apparently associated with Genghis Khan’s entry into power, or it happened shortly before. Accordingly, a first wave of ousting the Yakuts from the Baikal region probably began in the 9th century AD. Originally, the Yakuts settled at the upper Yenisei. Proof of this view is found in the similarity between the very early “Tataric” and the Yakut languages, and the similarity of numerous cultural elements of these Altai peoples. Their self-designation “Sacha” is supposedly the result of remains of Turkic peoples at the upper Amur and the Selenge, which call themselves “Sagay”, “Sachaz” or “Socha”. It is for the same reasons that they are also viewed as inhabitants of Dzungaria, as a “Socha” tribe already existed at that time. However, the Yakuts were always a uniform ethnic tribe who was probably ousted from the Sayan-Altai Mountains.

|

Who were the ancestors of the Yakuts? Russian researchers believe they were the Quryqan (Ruan Ruan – Juan Juan), who resided west and south of Lake Baikal, who were referred to as “Ku-li-kann” in Chinese sources, a Turkic people who lived north of the Eastern-Turkish Kingdom from the 6th to the 9th centuries AD and whose name appears in the Orkhon runes of the 8th century AD as well. Russian scientists believe that by extending their area of power in the early 9th century, the majority of the Quryqan were forced to move north. This sudden emigration is proven by burial objects. A smaller part stayed in the country, being subject to a first Mongolization by the Kitan (1), and was incorporated by the Buryats after their invasion. This theory is rather plausible because the Buryats invaded their current territory in several smaller hordes. Had they encountered the still closed mass of Yakuts settling here, being fewer in number, they would have lost to them without any doubt. This slow takeover was only possible because the country has a relatively sparse inhabitation. The Kitan on the other hand, who progressed during the 9th century AD, were a war power who had to be capable of ousting the Yakuts. Certain similarities of the Buryat and Yakut cultures are explained by the fact that parts of them must have had the same ancestors. The Quryqan invasion is placed in the Iron Age, i.e. the beginning of our common era, as proved by pre-historical finds. Nothing certain is known about their whereabouts before this period. The above findings are convincing because the Buryats did not pursue pottery. The Quryqan, however, left remains of pottery behind that bear a striking resemblance with those of the Yakuts. This cultural element connects them to the other Turkic peoples of the Altai in the 6th and 8th centuries AD as well, who also produced rather coarse pottery (2), which is contrasted by their highly-developed metal works. Politically, the Quryqan belonged to a group of Turkic peoples in the Altai who shared the name “Tu-lu” or “Tu-lis”, under which they were referred to in the Orkhon documents. The first time they are mentioned is in Chinese sources due to their fight with the Turks (t'u-chüeh) another Turkic ethnic community of this area, in 552 or 553 AD. In cultural terms, these Quryqan and the peoples of the Altai area they were associated with resembled the Yakuts of today in many respects. The wore fur and wool garments. In their totemist symbolism, the horse was held in high esteem. They produced kumis from mares’ milk. Like the Altai peoples of today, they mounted the heads of offered sheep and horses on rods, and they worshipped the sky and the Earth. Their society was divided into classes. Moreover, they possessed a rich art of smithery, they pursued horse and cattle breeding, and agriculture.

|

- (1) Kitan or Khitan: a Protomongolian people from Manchuria that existed as early as the 6th century AD.

- (2) Pottery: During excavations conducted mainly by Petri around Irkutsk and at Lake Koso-gol after World War One, for the first time, pots of the same design and with the same ornaments were found, from which it was concluded that at least part of it was the work of the Yakuts, who must have lived in the area that is today classified as Buryat territory. These finds belong to the early Iron Age. In the Neolithic Age on the other hand, the pots were thinner and unsuitable for transportation, which allows the assumption that a settled population resided in this area at the time. Also, not a single geometrical ornament of these products shows parallels with the Yakut pottery. In contrast, its similarity to the pottery of the Iron Age is striking. Not only are materials, production method and ornaments similar, but ceramic production must have been left to women at that time, which is concluded from the strikingly small fingerprints. Pottery products of this kind were also found in the currently Buryat area of settlement at the upper section of the Lena river, in the Silka valley and at the Selenge, and they were common even in Mongolia. In the West, the area of these ceramics was extended beyond the Sayan Mountains to the eastern hillsides of Minusinsk Hollow and the area around Krasnoyarsk. Further south, in the Russian Altai, ceramic products of this kind were produced until the 8th century AD. This means that the Yakuts probably formed a group of pottering tribes of these territories around them.

Tokarev believes that the Quryqan could be ancestors to the Buryats, but he does not further comment on this hypothesis. It is generally doubted today.

|

Ethnical mix: Due to the Yakuts’ relatively late immigration, a mix of the peoples originally inhabiting the Lena areas must have taken place. There are two distinct types: Mongolids with a flat face and nose, and some who appear more Turganid having longitudinal faces and a narrower, further protruding nose. This express two-way division does not generally apply to the apparently Europid Dingling (1) ethnicities, as they mainly belonged to the upper class and the leaders (chiefs). The majority of the Mongolids were nomad shepherds (and subordinates). Until the Turks invaded, the Tungusic peoples were the leading class.

|

- (1) The Dingling were a South Siberian people. They initially lived at the upper section of the Lena river, west of Lake Baikal. In the 3rd century BC they began to expand in a western direction. They were part of the realm of the Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu)..

|

- Find further information on nomads on horses at: „History of the Equestrian Nomads“

|

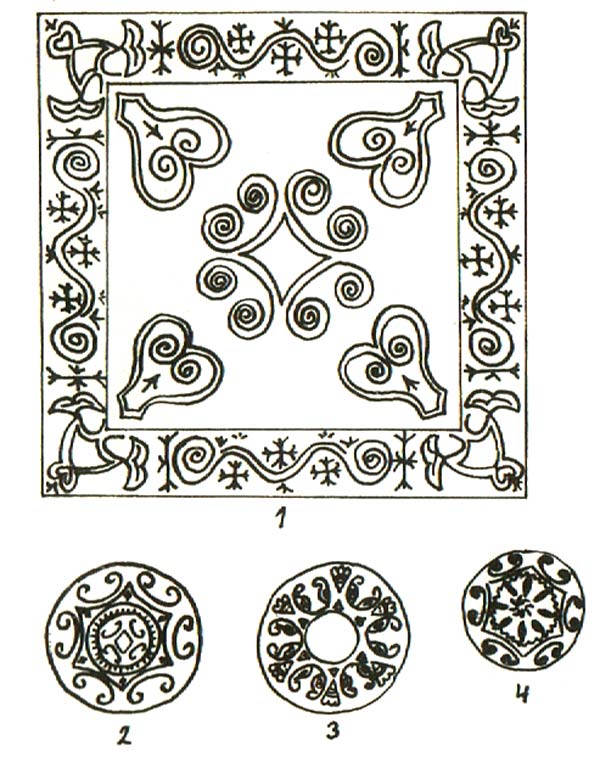

The Ornaments

|

In general, a lot remains unclear when viewing the Yakut people historically. Much about their spiritual culture is still unproven. For the moment, only a description of their ornaments can be tackled, accompanied by references and comparisons to other Siberian peoples. If we manage to read the symbolic content correctly and to track it back to earlier times by means of archaeological finds their spiritual culture and their past can be identified. If a motif is considered holy or worthy of protection, it is reproduced many times, which in turn helps it to become a decorative element. Thus, the ornaments constitute one of the most independent elements in the culture of a people that is more difficult to change than objects of a purely material culture. The ornament thus becomes an important witness wherever written sources are absent. In ornaments, one can find indications of contact between peoples and of their mixes, and these signs are often more reliable and durable than anthropological or linguistic features.

- Ornament studies for Siberian peoples were conducted by Finns: Sierlus studied the ornaments of the Ostyaks and Voguls. Laufer’s object of study were the Amur peoples far east, Ryndin observed Kyrgyz decorations, while the Buryat ornaments, which are the most important, were analyzed by Petri. The Ket ornaments were studied by Anugin, those of the Altai people by Anochin.

- Jochelson visited the Yakuts in the years between 1884 and 1894 and between 1900 and 1902, while Sieroszewski also spent 12 years among them in about the same period.

Metal processing was left to professional blacksmiths. Other works on various kinds of materials were manufactured at home, especially during the winter. Men produced wood and bone carvings with their knives. Women were left to do all needle, fur and leather works as well as braiding, glueing and pottery. |

- see more information about – Ornaments of the Turk-Mongolian tribe (cloths, ceramics, handbags, tools etc.)

|

Beadwork: This technique has only been applied in recent times, as colored glass beads were introduced by the Russians. The technique is popular with both the Paleosiberian and the Ugric peoples. Mostly the beads decorated women’s fur pants, followed by knee-high fur boots and colored little hats. Decorative plates braided with beads are found as the fringes of saddlecloths and on bags.

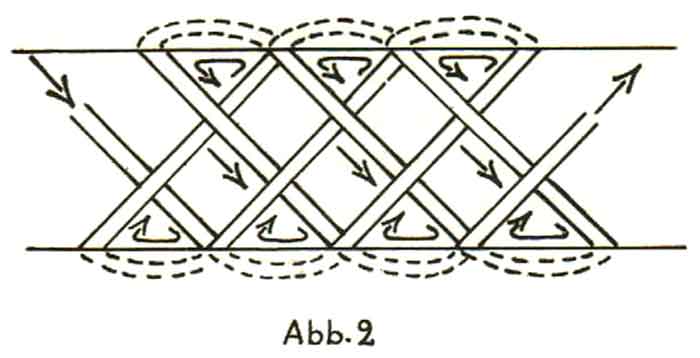

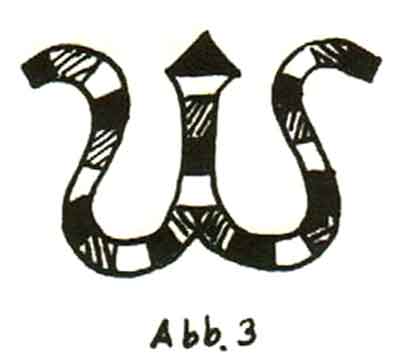

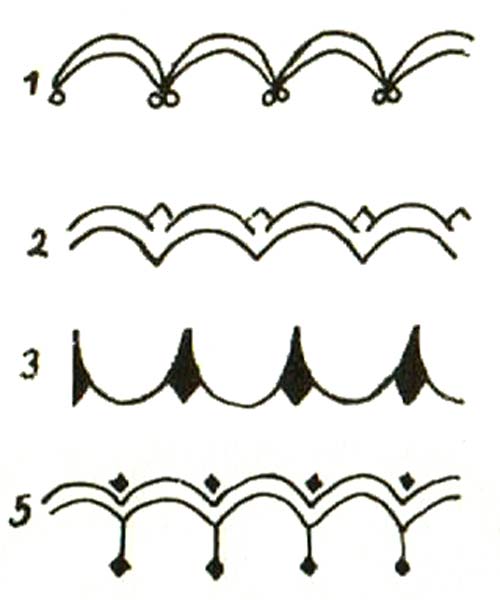

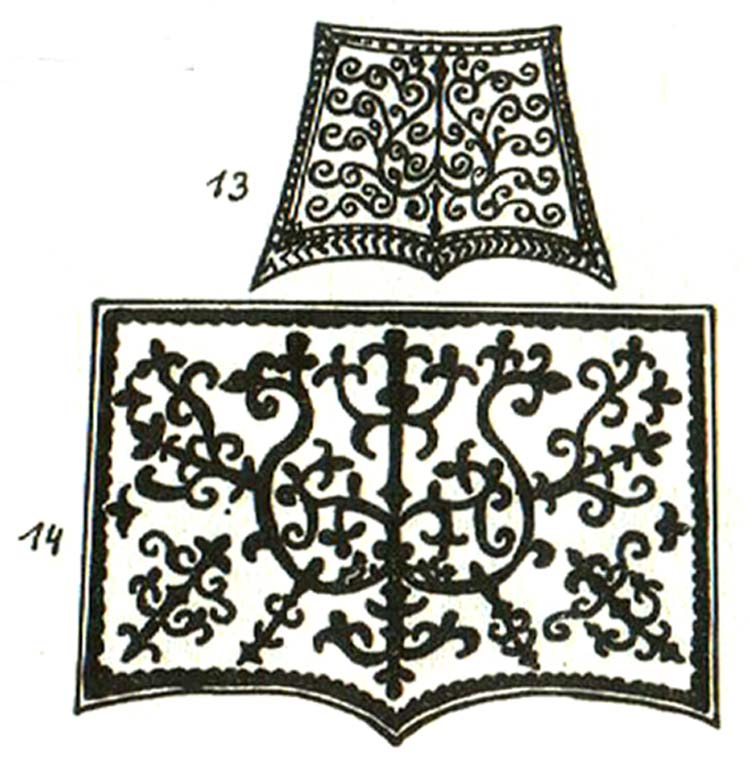

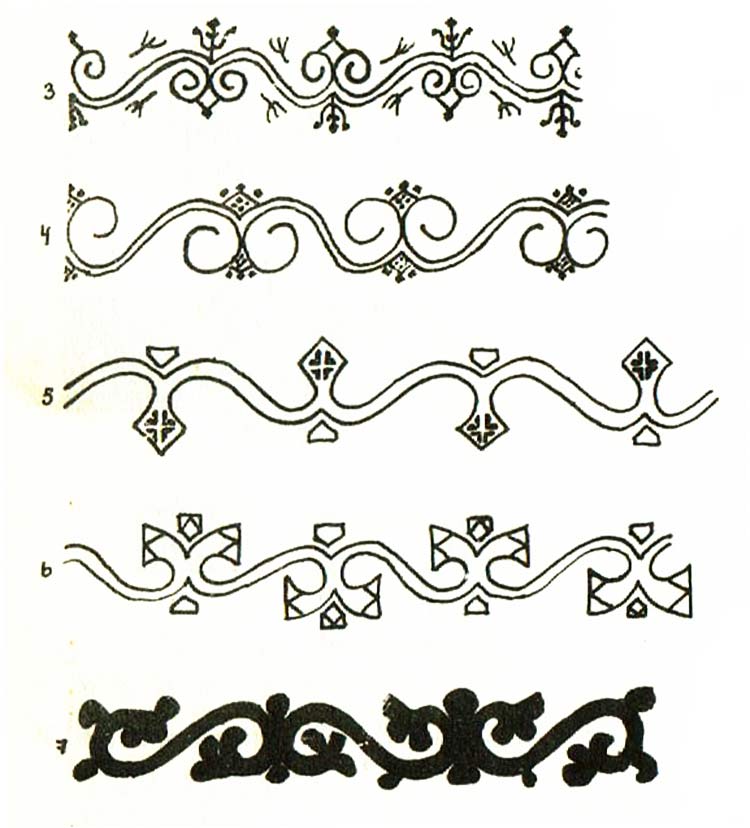

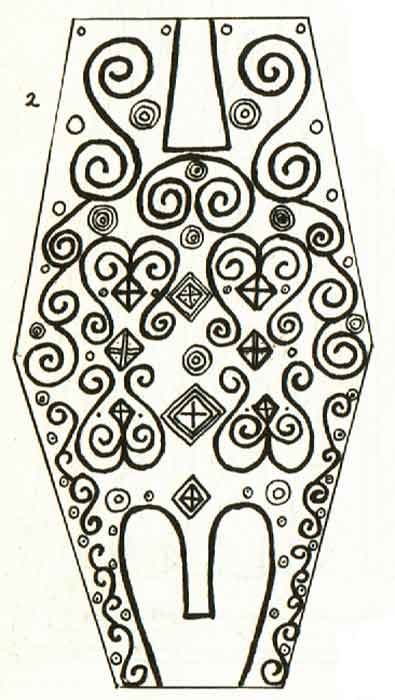

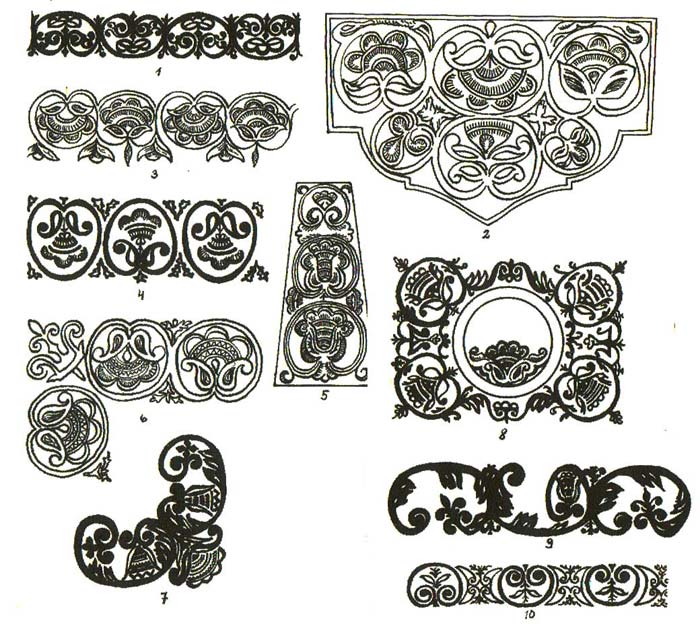

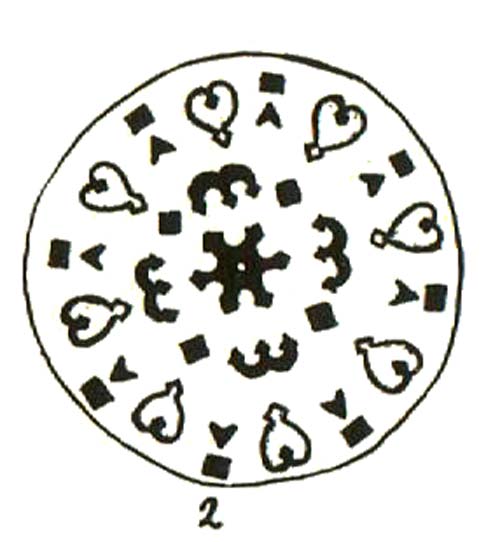

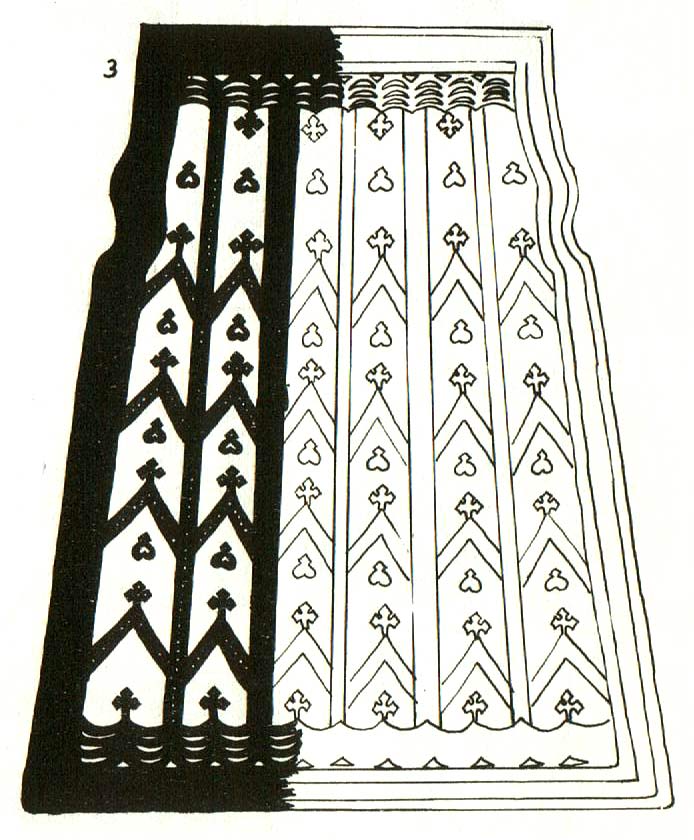

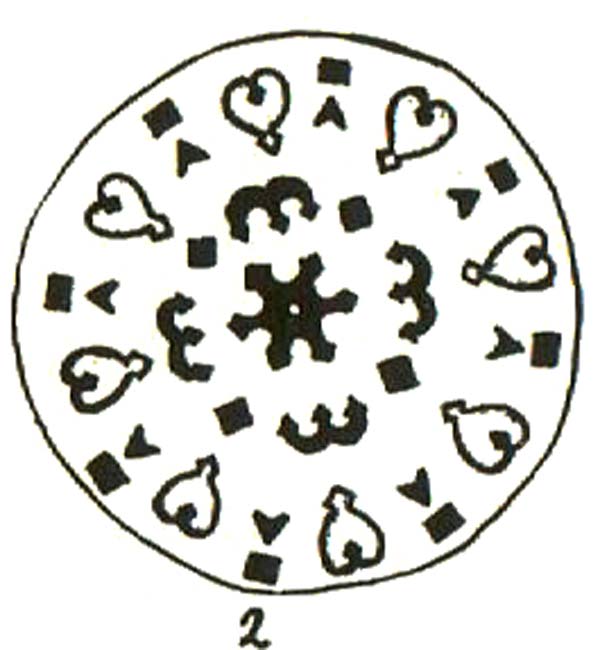

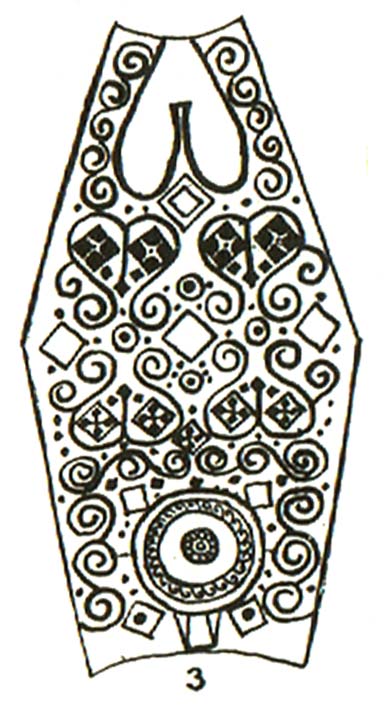

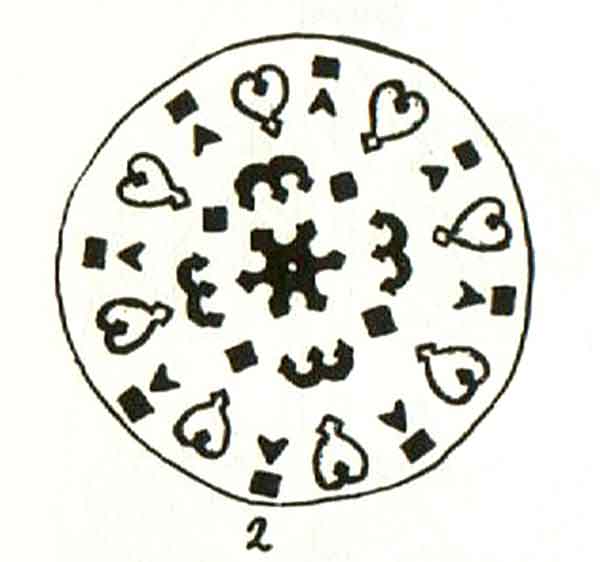

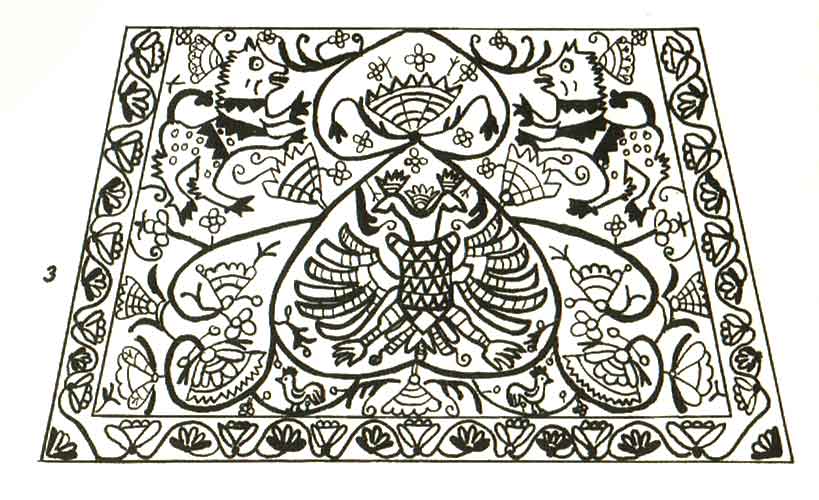

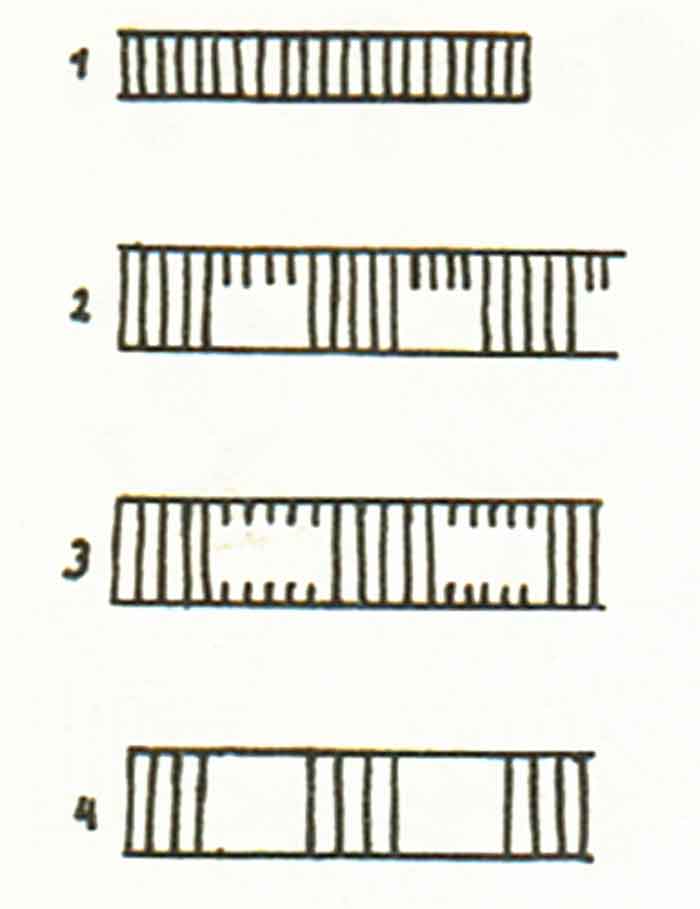

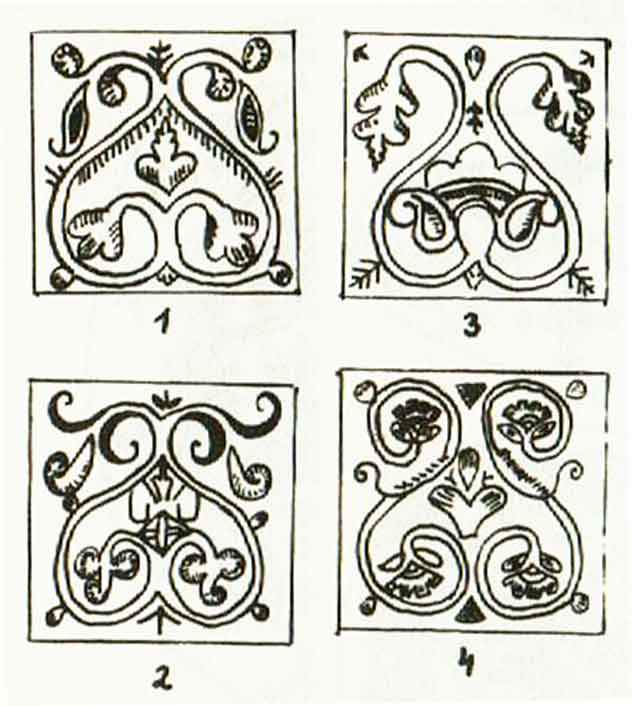

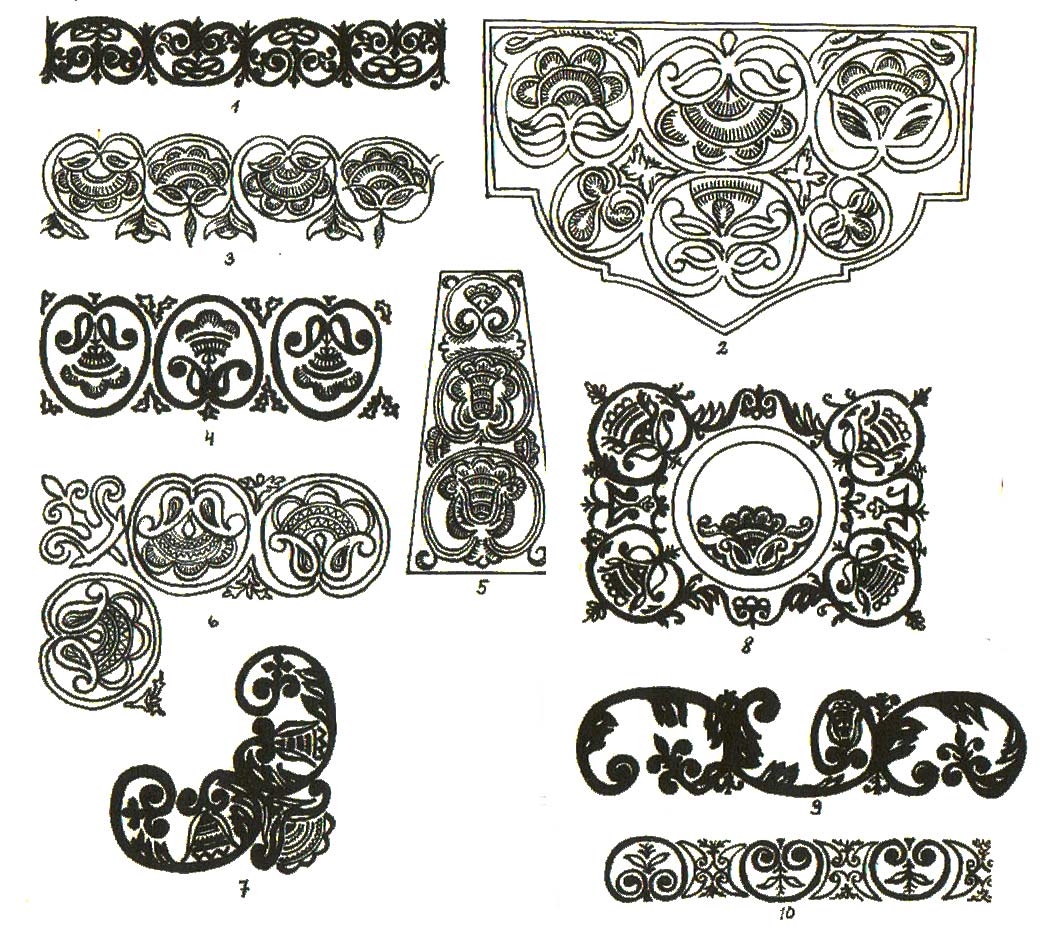

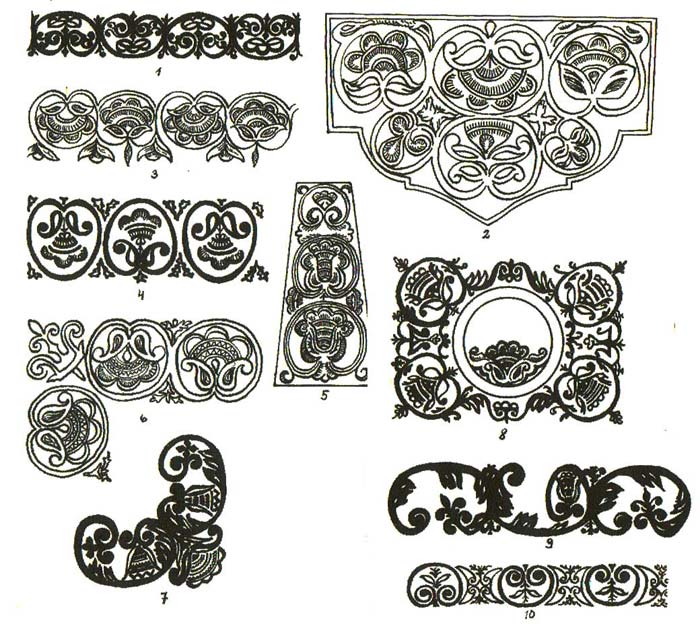

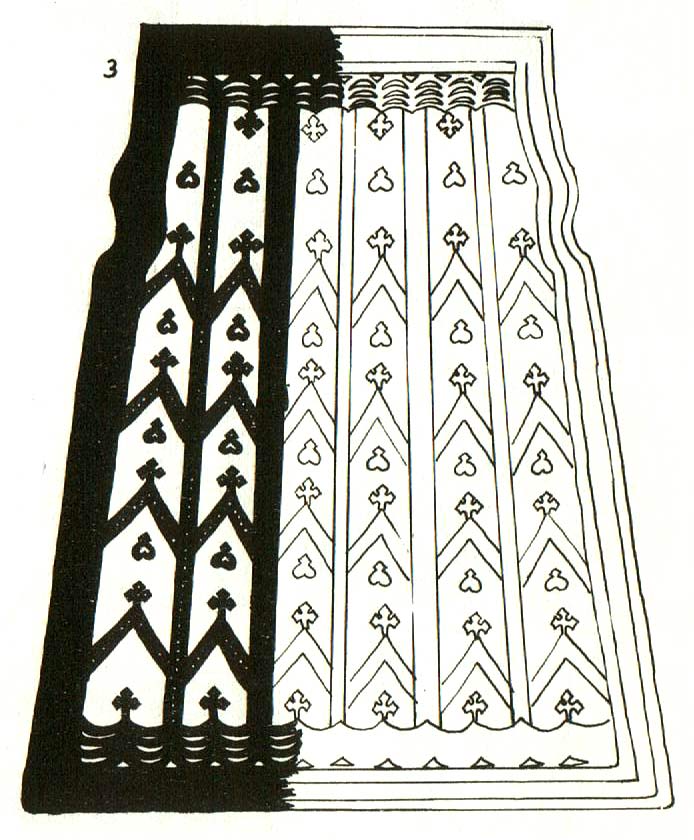

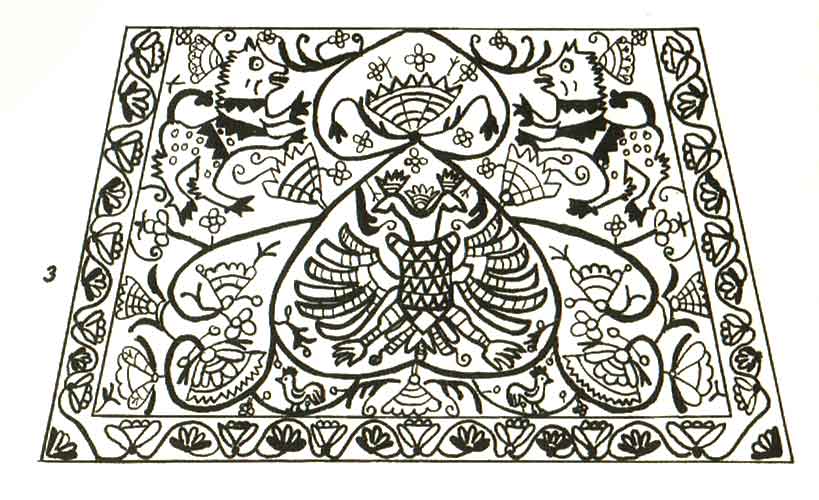

Multi-color embroidery: The material used for multi-color embroidery, mostly only loosely twisted silk threads, was obtained from Russian or Chinese merchants. Imported wool cloth or chamois leather (leather produced by tanning with tanning materials based on oxidizable fats) were used as supports. Three kinds of ornamental stitches are known: the stem stitch, which looks like a single twisted thread, the Mosul and the Yanina stitches, better known as the herringbone stitch (fig. 2) and the satin stitch, respectively. The stem stitch mainly serves the purpose of re-bordering the patterns applied with the herringbone stitch, often in a different color (fig. 3). The colors of the accomplished patterns are kept very harmonious and restrained.

|

In satin stitching the silver thread introduced by the Russians is used. The figurines of the pattern, cut out of cardboard, are overstitched with yarn. Strangely enough, the Yakuts lack tambour embroidery, which is otherwise common and characteristic for Russian, Chinese, Kyrgyz and Buryat works (the embroidery hoop that the material to be stitched is tightened to is referred to as the tambour). It was very frequently employed in pre-Christian times, as confirmed by finds in Noin Ula in Mongolia (kurgans from the 3rd century BC). The backstitch was not a decorative stitch for the Yakuts either. On thick pieces of suede or fur the material was not pierced completely. Only specific objects were ornamented, such as large panniers, saddlecloths and parts of little summer hats, fur hats and fur gloves. Unlike the Kyrgyz, the Yakut women did not have coats decorated with embroidery.

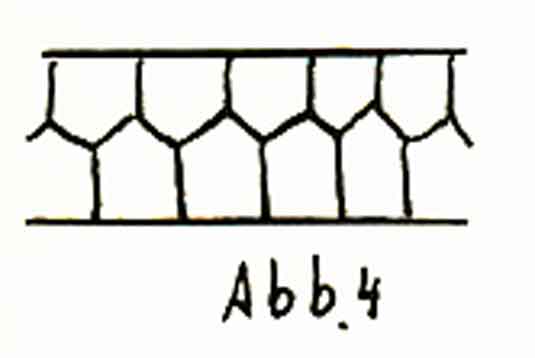

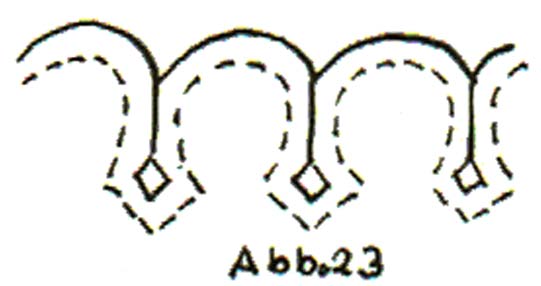

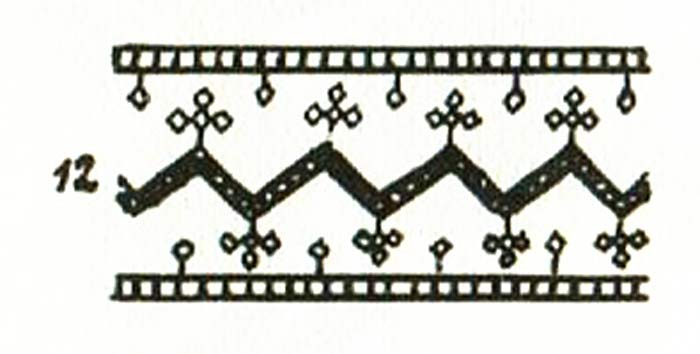

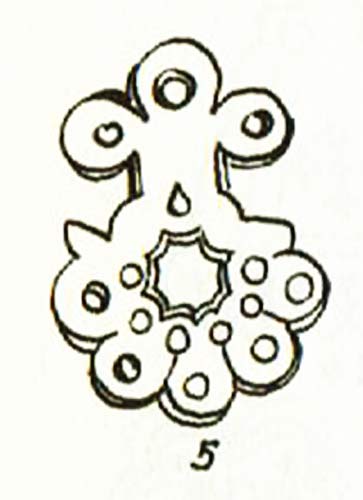

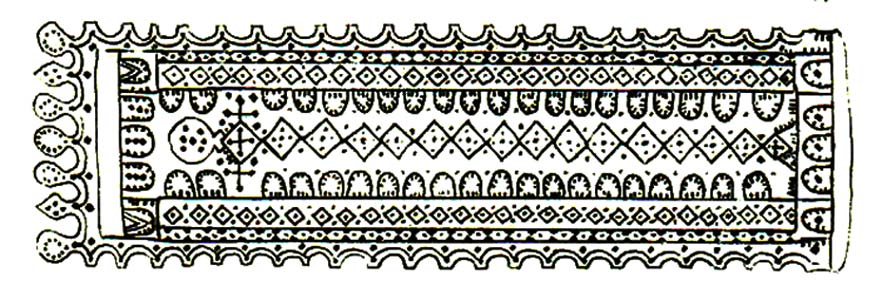

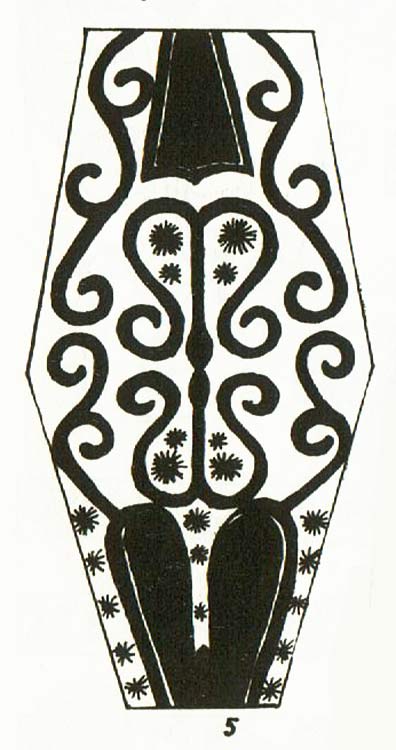

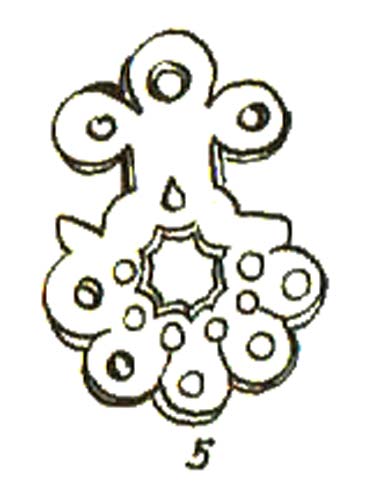

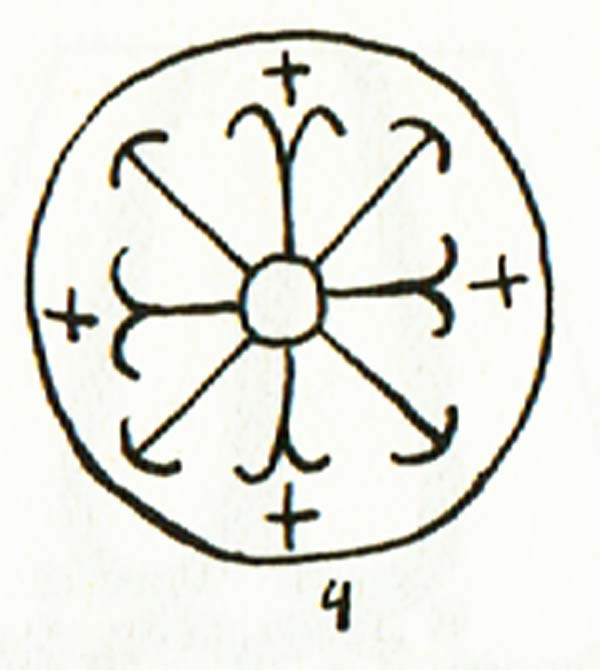

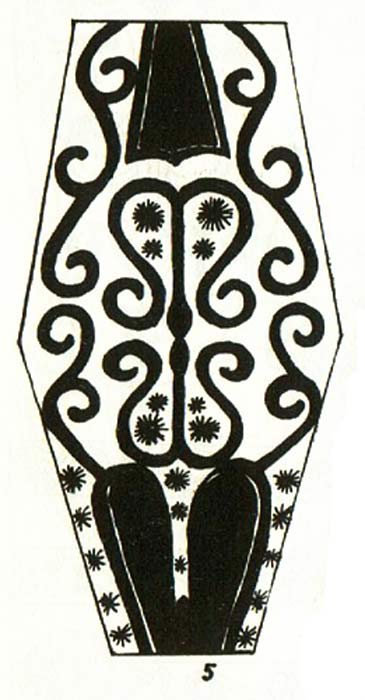

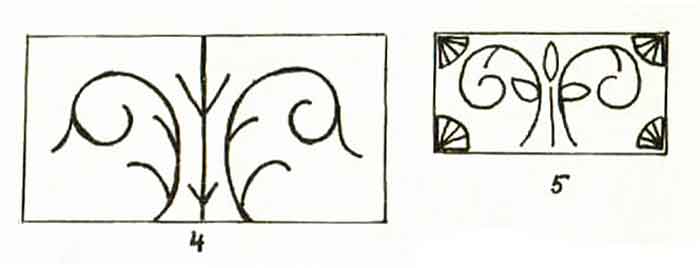

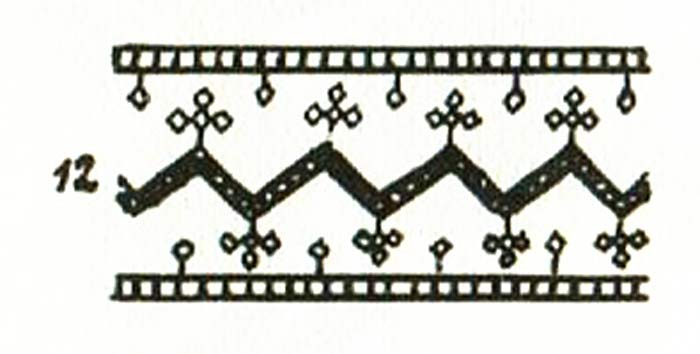

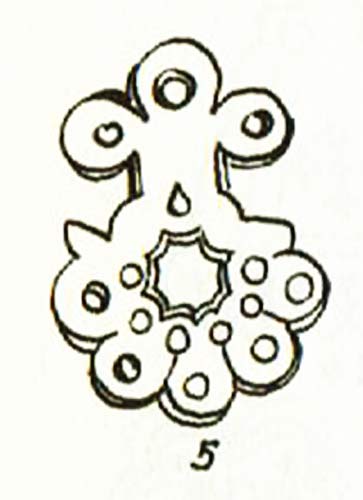

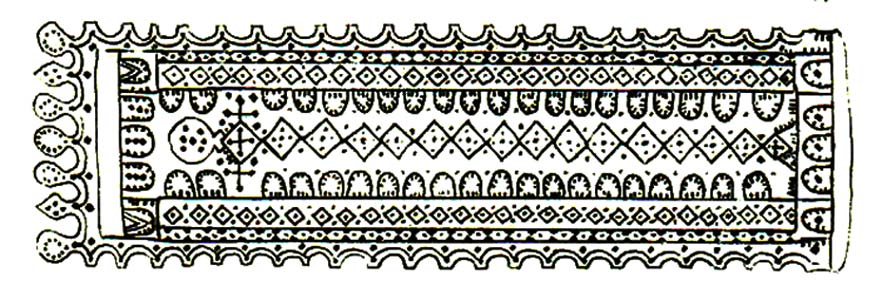

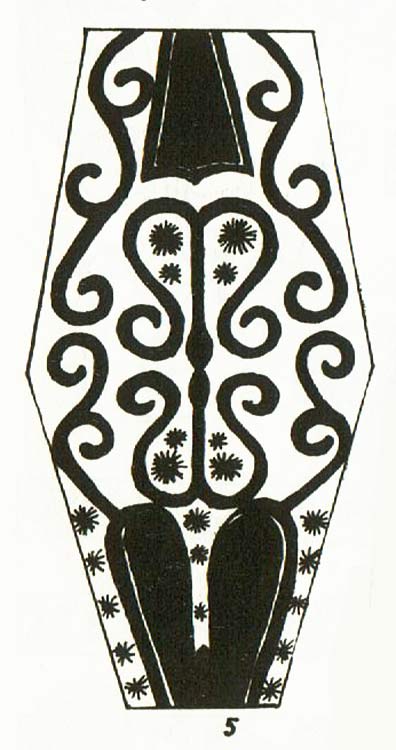

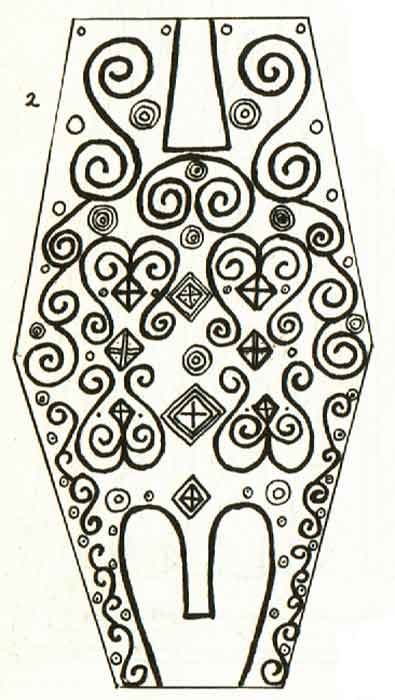

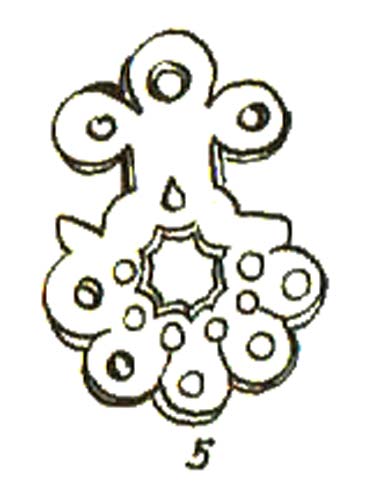

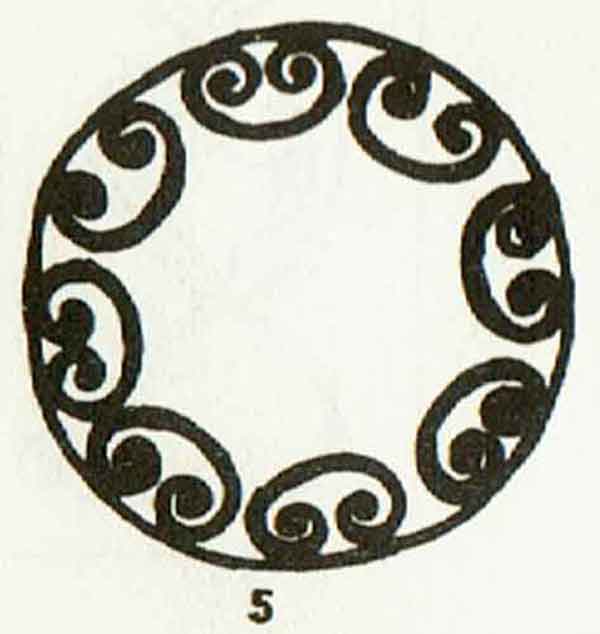

Birchbark containers were overstitched with hoops made of birchwood using simple stitches (figs. 4 and 5). This rendered the containers more durable, and the seams made of horsehair yarn served decorative purposes at the same time.

The dark, interrupted bark streaks form geometrical patterns themselves. Another type, made of stamped metal foil obtained from teabags or colored paper have a decorative effect. These techniques, however, are probably not of indigenous origin. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Appliqués, textiles and fur mosaics: Certain shapes made of leather, fur or textiles were applied on a support of a different color. They are glued on, while the edges are fixated with stitches. This shape was not common with the Yakuts but found in Noin Ula and in Pazyryk kurgans. |

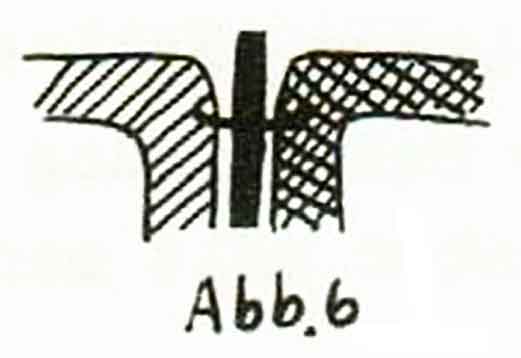

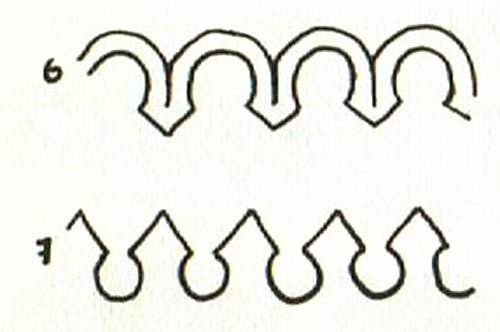

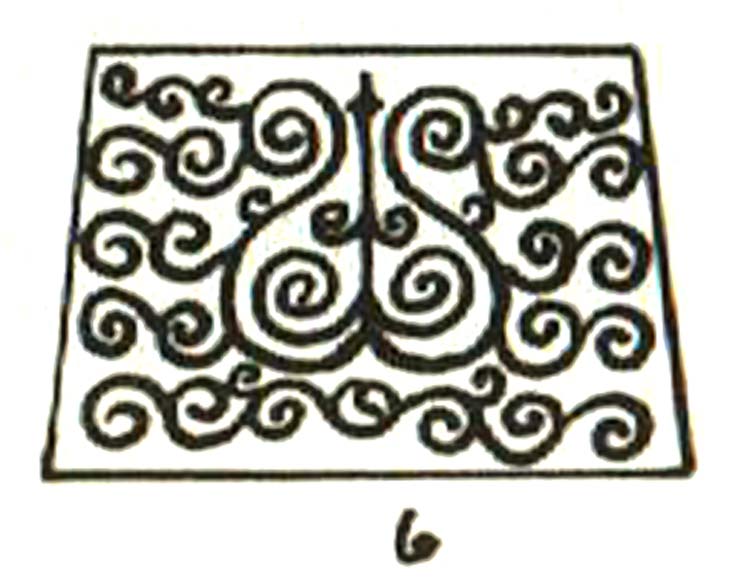

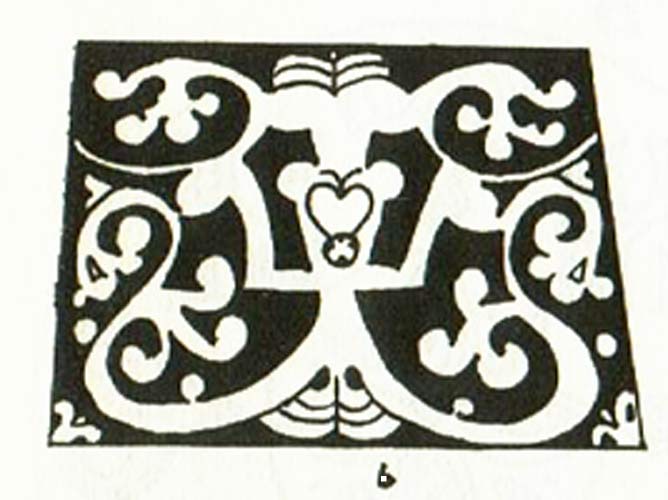

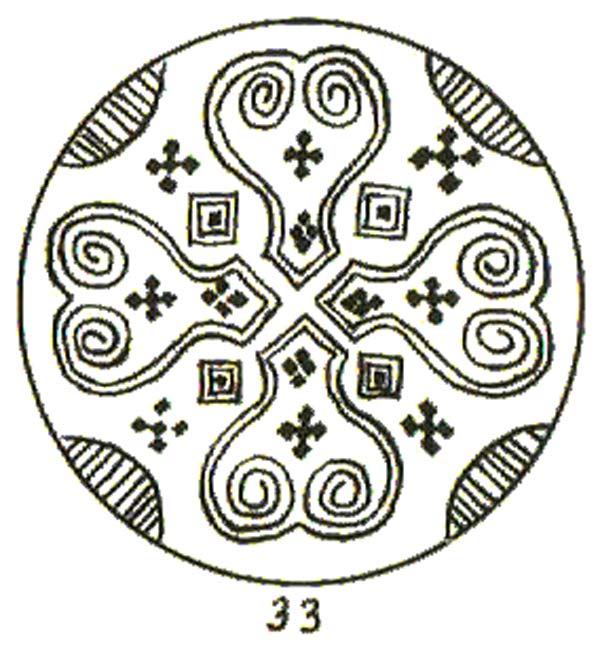

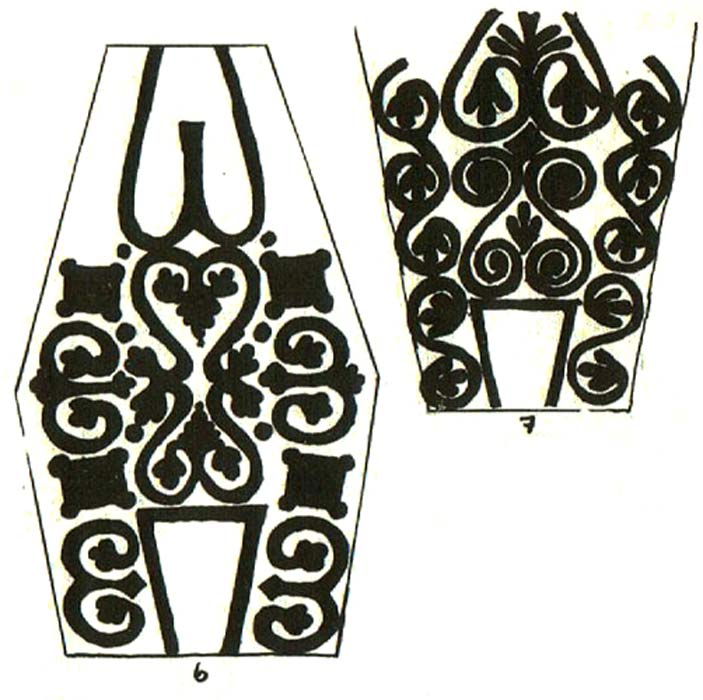

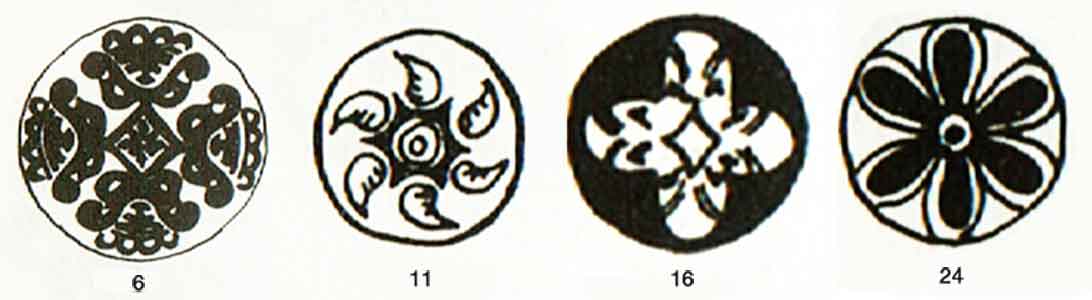

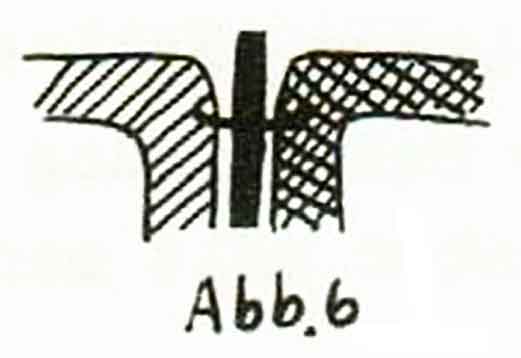

The Yakuts also used mosaic patterns. They are the result of small pieces of colored cloth being cut out with scissors and sewed onto one another. The patterns were rectangular, and in order to avoid showing the unsightly left side, the colored surfaces were sewed onto the edges on sackclotch in their entirety. Even more variety could be created by adding a narrow piece of cloth in a third color into the seam (fig. 6).

|

|

|

|

|

Fur mosaics were produced exactly the same way, except without the decorative streak in the center of the seam. Solid hemp threads served as a stitching material. Small iron broaches with a wooden grip were used for working. These works correspond to the fully known patterns of Paleosiberian fur works.

Carpets, saddlecloths and small satchels mostly used for carrying tobacco are decorated with these patterns.

|

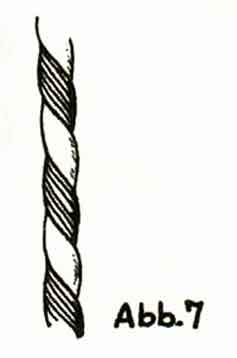

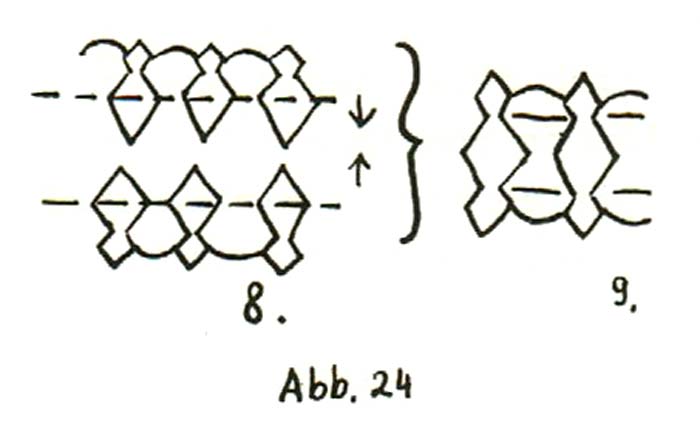

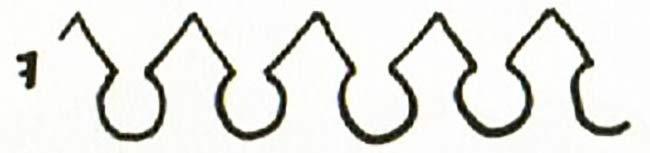

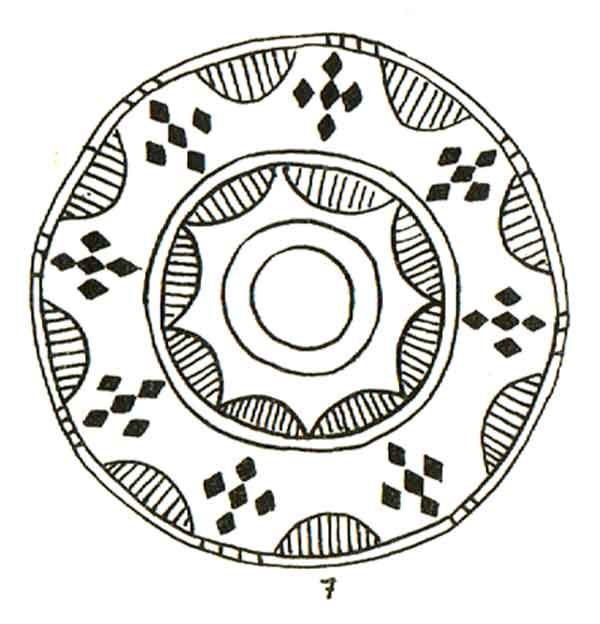

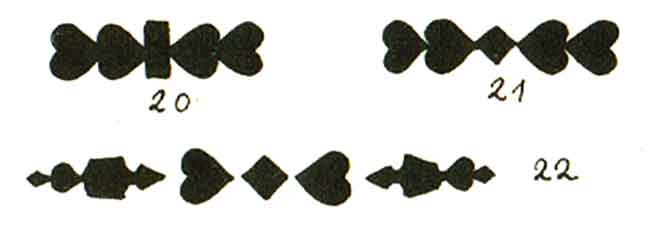

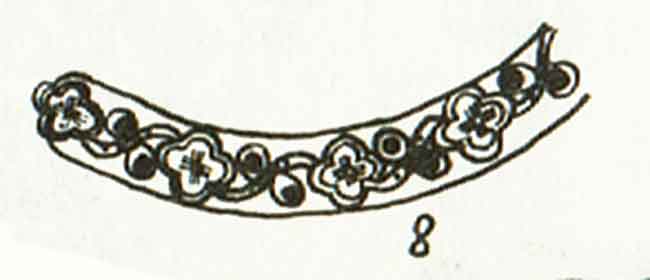

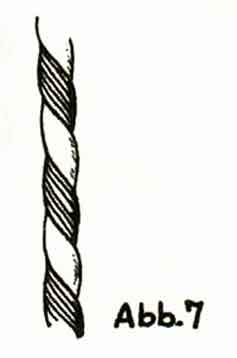

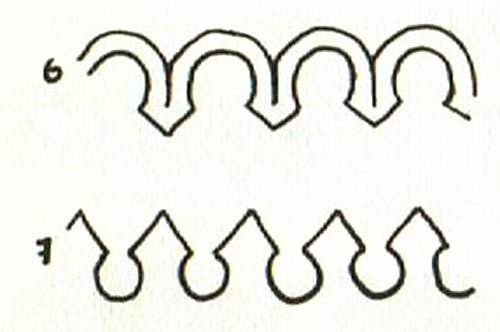

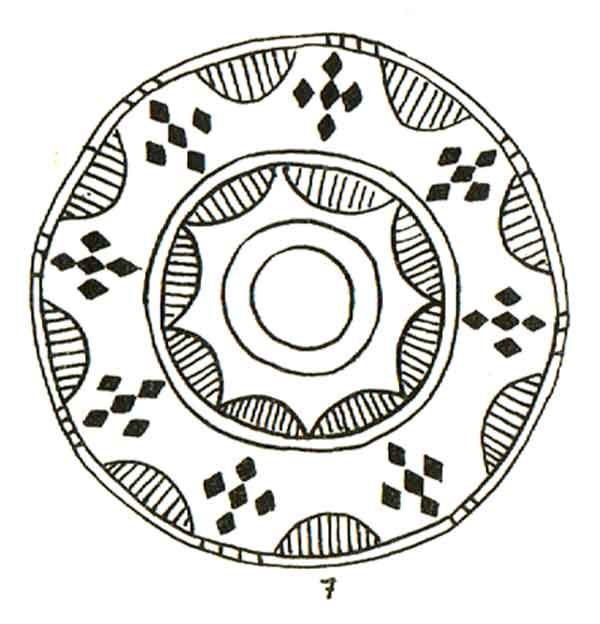

Braiding works and the production of straps: Weaving and basket weaving were unknown to the Yakuts. What they were good at is producing mats from grass and straps out of horse or reindeer hair. Straps were made of tightly twisted threads that were wound around one another. To retain patterns, dark and light cords were used (fig. 7).

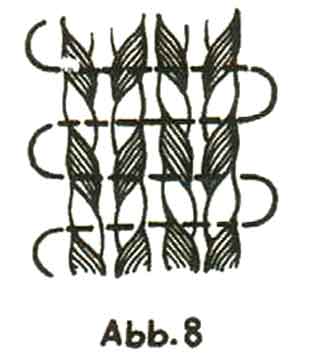

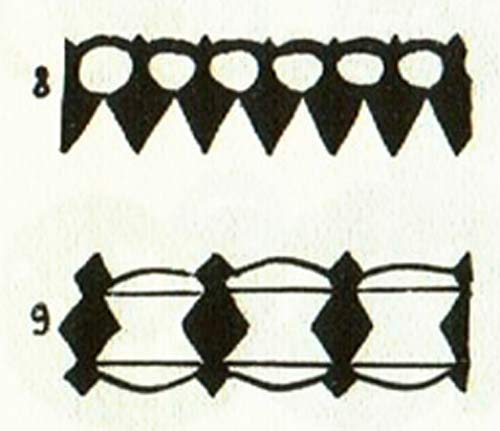

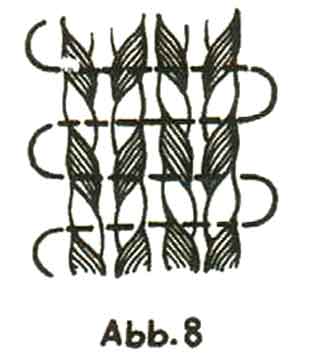

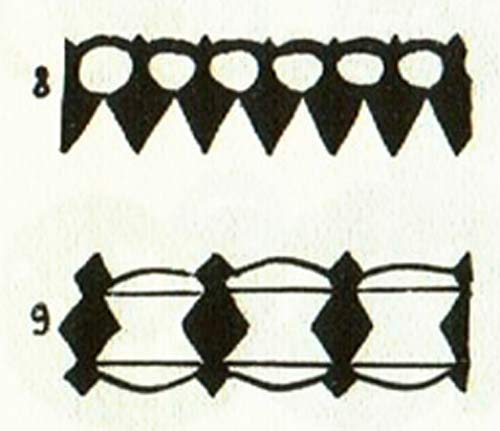

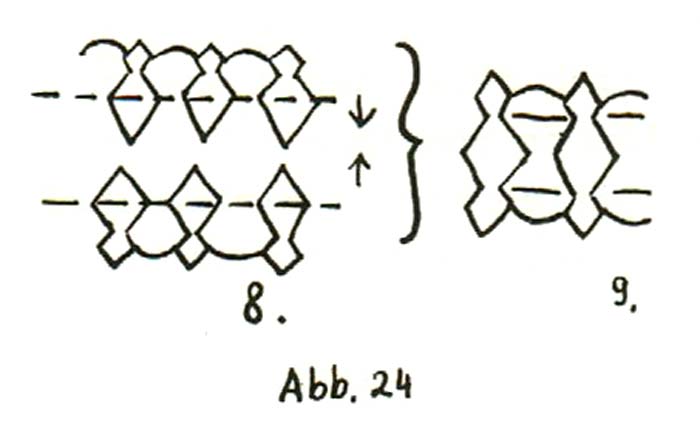

Several of these straps put next to each other, running up and down, create a zigzag pattern (fig. 8). This is also the method by which the Yakuts produced mats out of reeds. Poorer people used furs as supports for sleeping. However, the individual straps were not threaded but braided like plaits.

|

|

|

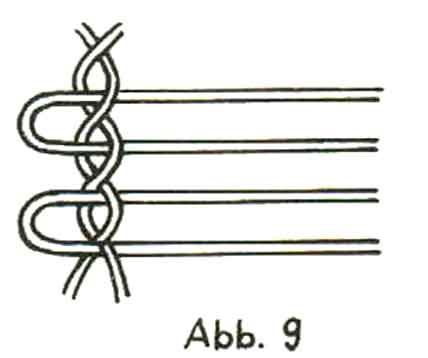

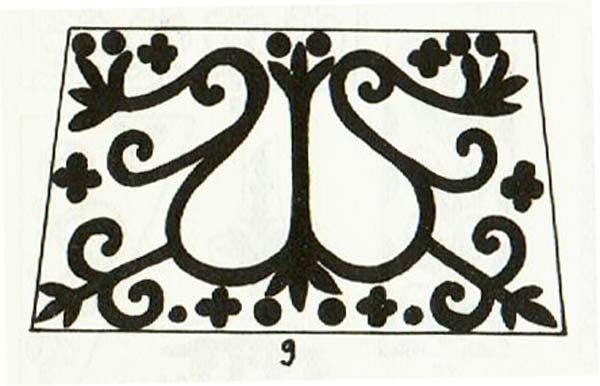

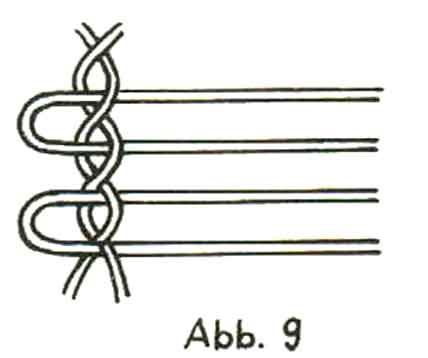

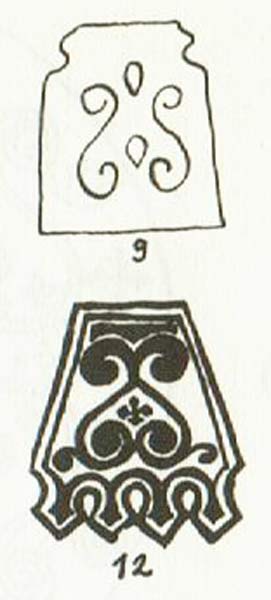

(fig. 9) The braiding technique was not applied by the Yakuts. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

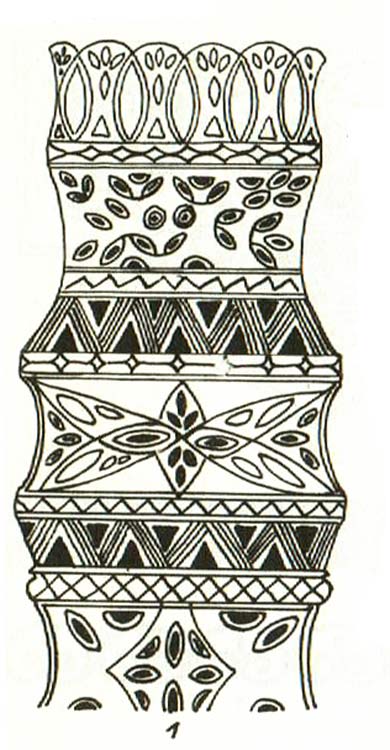

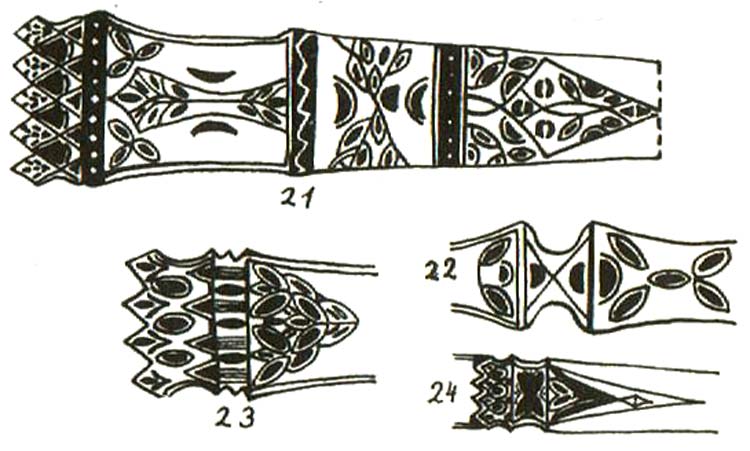

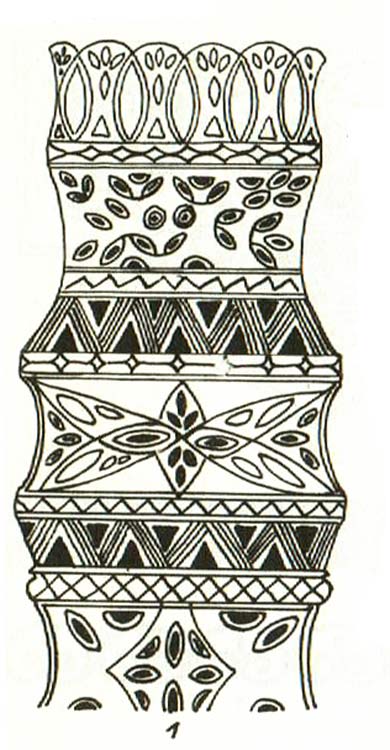

Pottery: Chamotte, which is frequently found, except in the north, is used as the raw material. Preparation includes mixing clay with finely struck shards of old containers. The potter’s wheel was unknown; for shaping the object a simple spheric or semi-spheric stone and a little modelling plate were used. To achieve a circular shape, several circles made of a type of purple willow were utilized. The pots were coated with wood and baked several times until they had a red glow. In order to cure them, hot water mixed with one or two tablespoons of milk were added when extracting them from the ashes in a heated condition. Glaze of any kind was not known. The ornaments were imprinted with wood stamps before the clay was baked. Very often they are found as additional decoration on draw beads. The clay containers were never painted; the ornaments were generated solely by stamps and fingerprints.

Mongolian and Tungusic ethnicities did not have their own pottery works.

Needless to say, there were numerous taboo regulations due to the fact that pottery was considered “impure” and that clay contained a type of earth spirits or chthonic possessors (chthonic spirits who bring life and fertility but also death). That is why, for example, it was avoided to leave the containers outside during natural events like storms, because it was not a good idea to allow them to break. The same fear arose when someone found a piece of a tree hit by lightning among the wood during the firing process. Sometimes the mere fact that the pure spirit of a domestic stove refused to unite with the impure spirit of pottery in the process of firing was reason enough for the pot to burst.

|

Ornaments on wood and bark

|

For more delicate objects, which were ornamented as well, birch wood was used almost exclusively. Birch wood was an extremely popular material, being more durable and easier to bend. Tools included axes, knives and hand drills. This small, relatively bendable knife is still used today for producing ornaments.

Ornaments were scored or carved as semi-reliefs using the so-called bevel cutting technique. The wood was not varnished. Fabricated objects, such as the kumys cup, were simply rubbed with butter or cream to prevent the wood from drying up or splitting. Painted ornaments were not found. Sometimes the wood would be painted dark brown in order to put special emphasis on the lighter cuts. Alder bark was used to obtain this dye. The black color was due to abnormal protrusions on the birch trunks, which form a deep black color in combination with ashes and cream. Protrusions of abnormal ulcers of horses beneath the fur of their armpits or at their groins were also used to obtain dyes simply by cutting them open. When the patterns were completed they were rubbed with cream in order for the bark to continue to be smooth and then glued on. This work was done by women, too, by way of exception. |

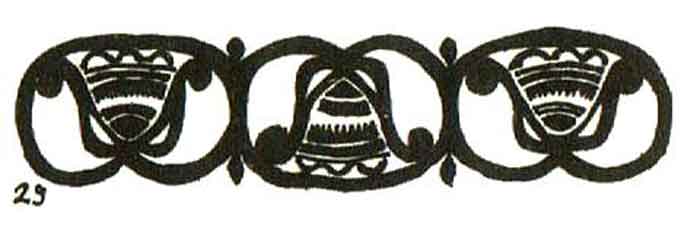

Chip carving was only used to decorate objects for storing kumys (the mares’ milk), cups used for beverages, and large scoops. The ornament consists of indented lines and broad oval immersions, which appear like leaves in the ornaments.

|

On wooden boxes, on the other hand, the ornament is generated by scored lines (scoring technique). When these are somewhat broader this technique can create the impression of a semi-relief.

|

| From birch bark as such, only the ornaments for wall hangings and doors or tents covered with birch bark and birch-bark cans were made. First they were soaked in water for a few days, then the top layer was scored off and they were painted. |

Manufacture of horn, bone and mammoth ivory: The same knife used for wood was also used for carvings of this kind. Since the Yakuts, as mentioned previously, did not create bimorphic representations because they did not want to disgruntle the spirits, it is more likely that carved figures made of mammoth ivory in semi-reliefs on little boxes and combs are from the New Age. For the Chukchi people, figurines like this one made of bone material were a much more common resource, and a tradition. This method of bone manufacturing was probably adopted from the Tungusic and Samoyedic peoples.

|

Smithery: When the Russians immigrated, the Yakuts were the only Northern Siberian people who had experience in recovering iron, brass, and copper. Silver, gold, and bronze had been used by these nomadic peoples in Southern Siberia for ages. The smiths themselves recovered ore from the resources they worked with. Other metals were imported. Manufacturing with cast iron was only introduced with the arrival of the Russians.

A large part of the silver was introduced in the form of coins that were reengineered into jewelry. Gold was less popular. Although an abundance of gold was present in the Lena area, it was not manufactured to a large extent. Instead, large amounts of ore and bog iron ore were smelted. To do so, holes in the ground that could be covered with a clay cap were used as stoves.

Ornamented iron objects hardly existed, with the exception of shamans’ jewelry, which it is more appropriate to refer to as sculptures than ornaments, as individual pieces were designed to represent certain objects. Important tools for the smiths were the bellows, hammers, pliers, anvils and rasps.

Sword-like weapons made of iron bear plain arch- or spiral-shaped ornaments on their blades. Individual objects were manufactured from brass. They include metal fittings on horse halters and shamans’ jewelry. Some products came to existence only under Russian influence, such as signets (hand marks and seals), crosses and tags. In a majority of cases the material was manufactured with ornaments made of silver. However, most pieces, even very thin coatings on wooden parts of decorative saddles were cast using the method of so-called “solid-shape adobe casting”.

|

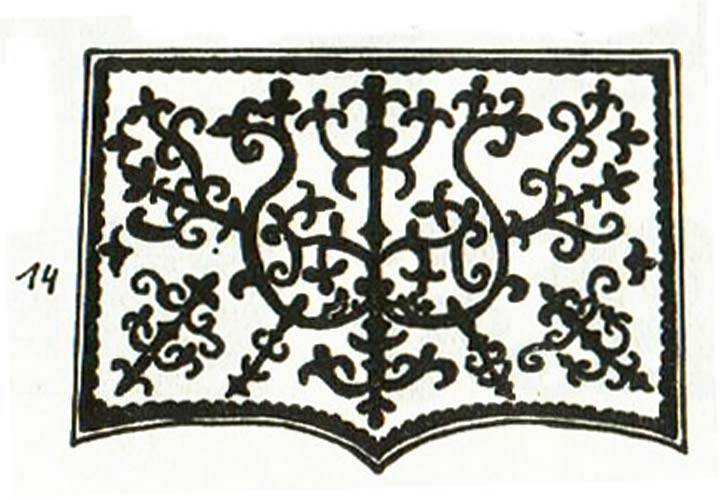

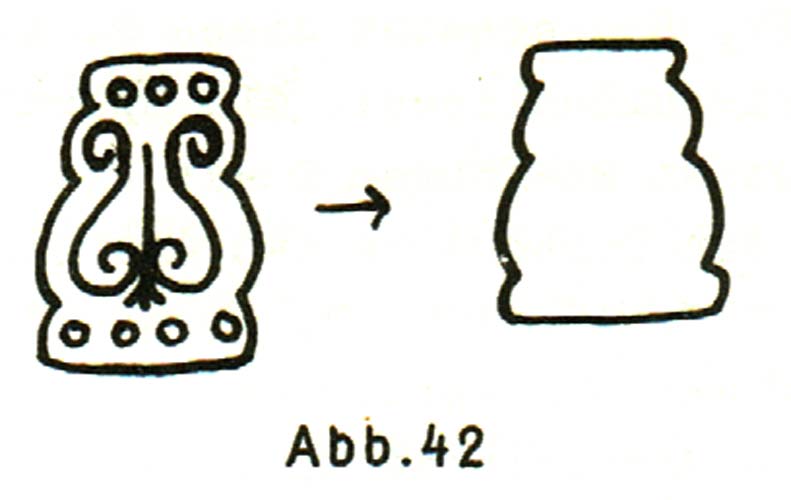

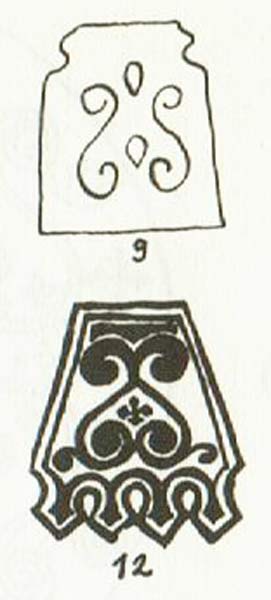

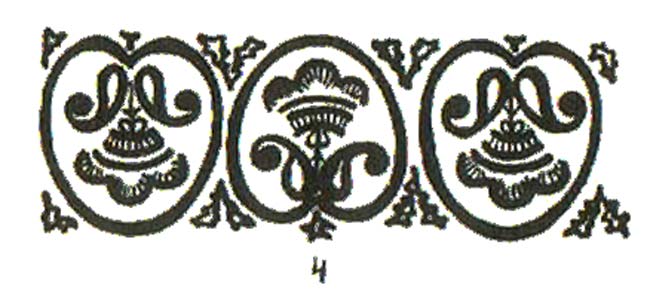

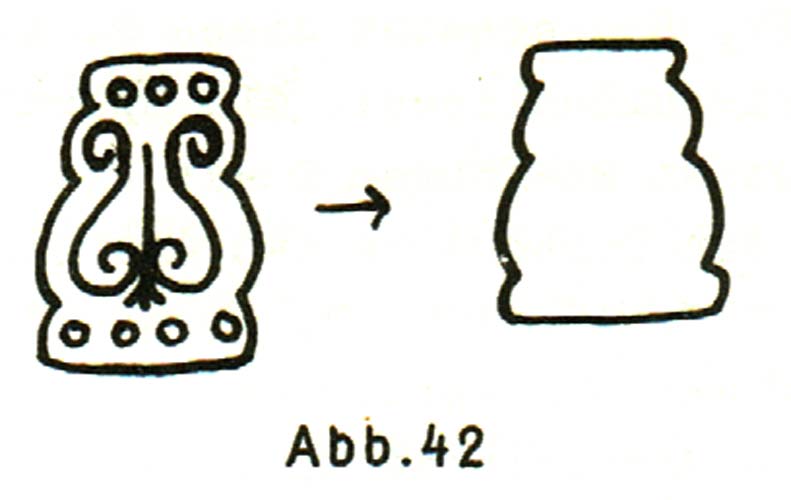

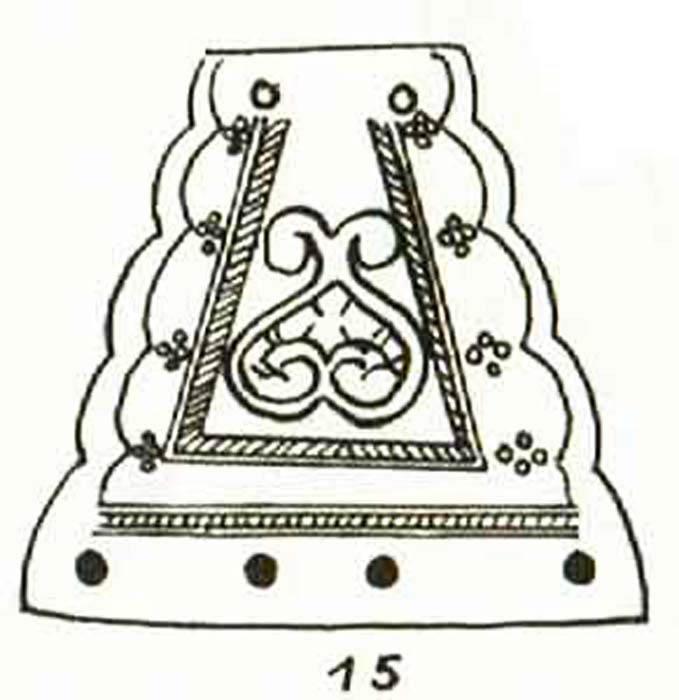

The actual ornaments were subsequently constructed using templates (Panel IV, fig. 9, template). Plain drawings were scored directly. |

|

|

|

|

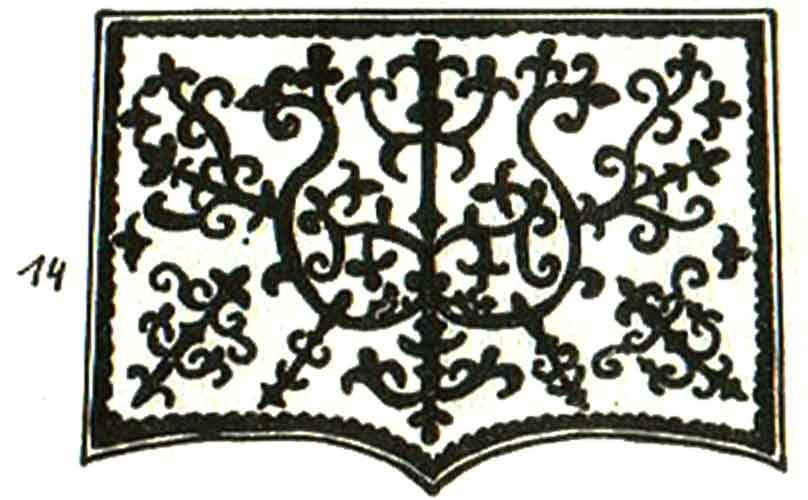

The ornament is either drawn with scored lines or by imitating a semi-relief technique by retaining the shiny surfaces as a pattern, very often bordered by a straight line, while hatching the ground with fine scored lines and filling it in with black. This creates a similar effect as chip carving, which is also the most popular technique for metal jewelry, especially in the Scythian world, where this animal style was produced. In contrast, the small decorative silver plates used like beads are really manufactured in semi-reliefs. The ornament was obviously stamped in. Smaller geometrical motifs were stamped on thinner metal plates. In addition, enamel was sometimes inserted into grooves that had previously been scored. The few enamel works that were found clearly indicate a Chinese influence. The material for enamel jewelry was tin beads and used shell casings, and it was brought in by the Russians. Wood and metal processing share very few common motifs. The complex patterns and the skill of its production culminated in stitchery, where flower motifs were made. The main motifs in processing metal were blossom, tendril and leaf motifs.

The art of smithery was handed down within families. As with the shamans, a differentiation was made between a blacksmith and a whitesmith. The smith was equally well respected in the eyes of the tribe members as the shaman because he too was equipped with magical powers over spirits. This power was based on the assumption that the spirits were afraid of metals. This explains rituals like that of removing all metal jewelry from the clothes of the dead. Fire must not be raked with an iron rod, or else its possessing spirit would be insulted. Evil spirits can be ousted by the sound of iron. Thus, the smith’s power was to restrain and release magical power. That way, his sphere encroached upon that of the shaman, which increased his position within the community. Smiths and shamans had a common patron: “Kytaj-Baxsy-Tojyn”. When he got irate about the smith, a red cow had to be offered to him. Also, the black shaman was offered a cow when he received the shaman garment at the beginning of his career. The female shaman “Makyny-Kysa-Tyny-Raxtax” received the same animal as a means of appeasement. Thus, cows were offered only to chthonic spirits (spirits of the earth). According to a Yakut saying, “shamans and smiths are from the same nest”.

Turkic smiths were already considered particularly skilled in early times, as reported by sources from the Tang period. Outstanding groups of smiths are said to have lived in the Altai of the 6th through 8th centuries AD, and the Yenisei-based Kyrgyz people of the 8th century AD are said to have been great masters of smithery. Jewelry was cast in silver before being adapted and subsequently engraved. At the Altai, this technique is very old, as demonstrated by finds of precious metal in kurgans from the Pazyryk time, probably from the 6th through 2nd centuries BC. |

The geometric ornaments

|

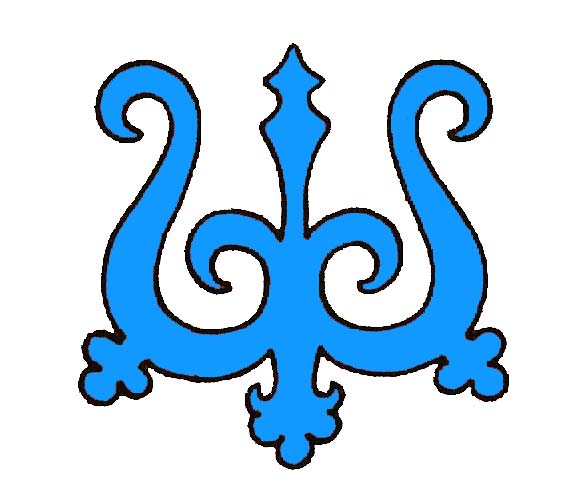

| Patterns that do not consist of spiral or plant ornaments will be referred to as geometric ornaments herein. No other ethnic group has as many motifs as the Yakuts, namely about 144, which are divided into ten different basic motifs. Figurative representation is unknown to the Yakuts, with the exeption of shaman jewelry. |

Basic motifs

|

| Lines and strokes: For the purpose of convenience we will make a distinction: Strokes are short strokes that are frequently repeated within a pattern, while lines continue for a long distance. A double line is found as a stand-alone ornament. |

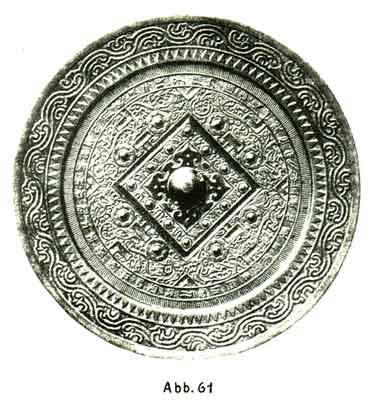

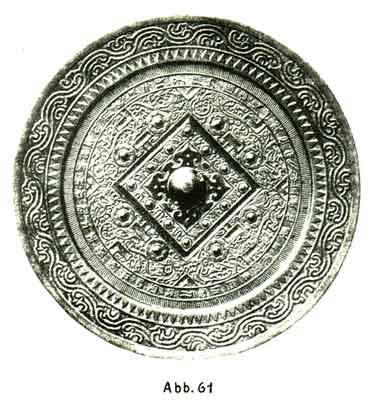

The crest ornament: These plain ornaments are widely common even outside the Yakut world, for example, with the Paleosiberian peoples, the Buryats and the Tungusic people. Even the Chinese use this pattern on their metal mirrors. In the Baikal region such motifs were found dating to the 1st millennium AD.

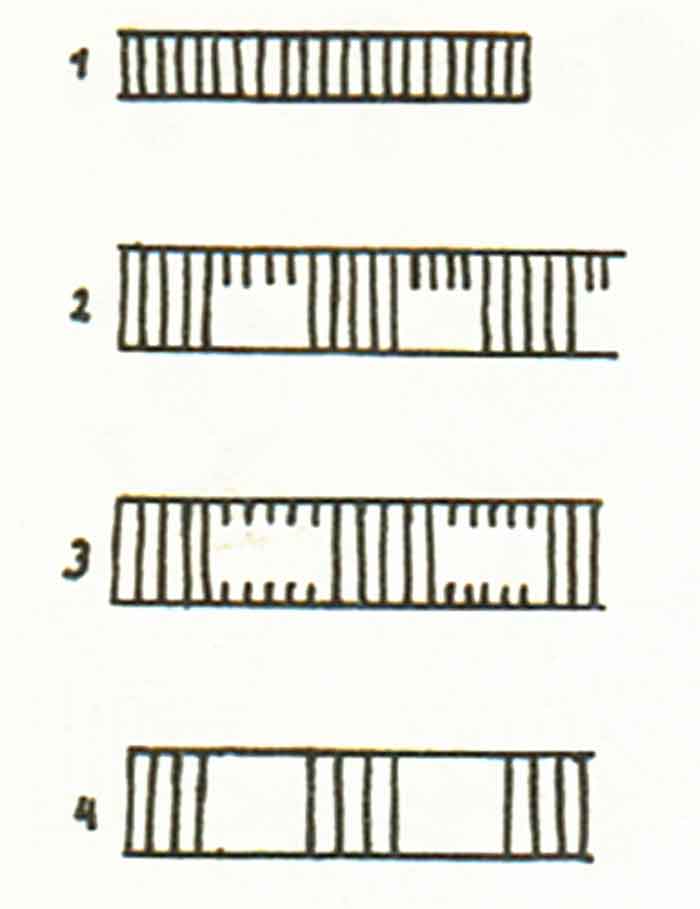

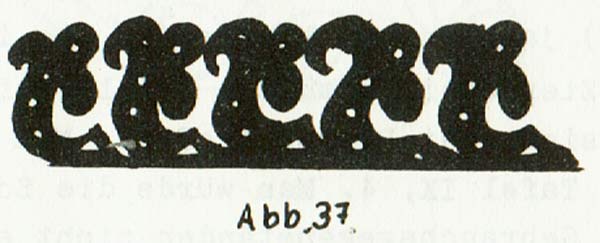

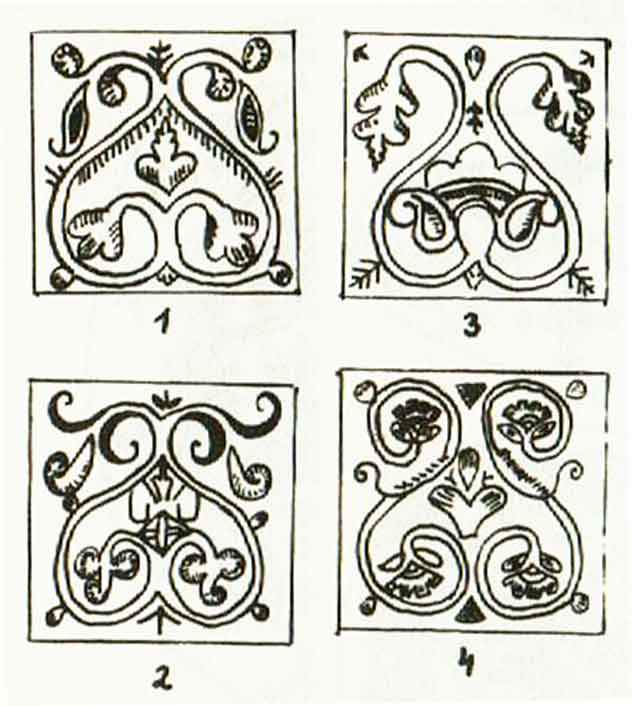

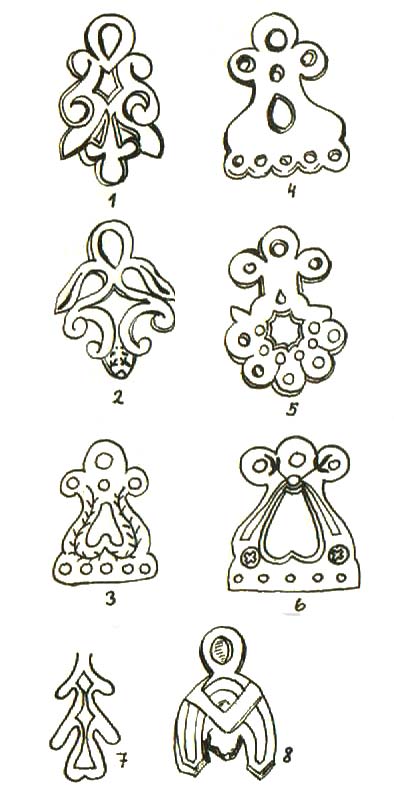

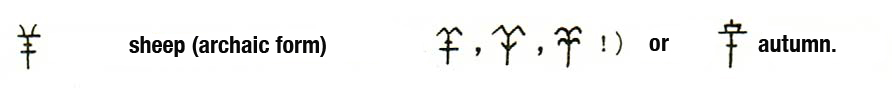

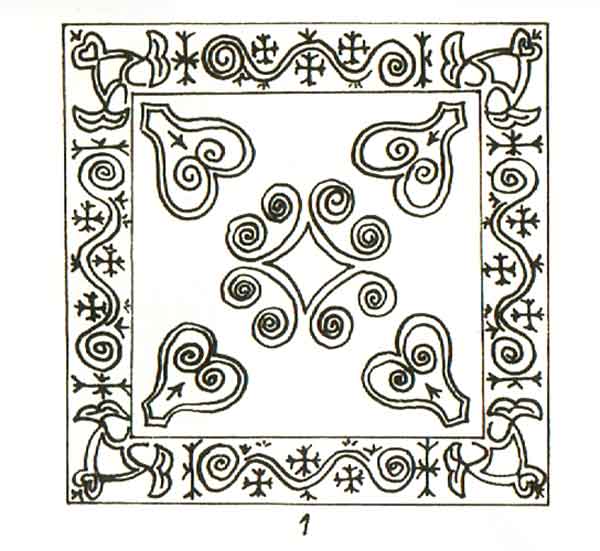

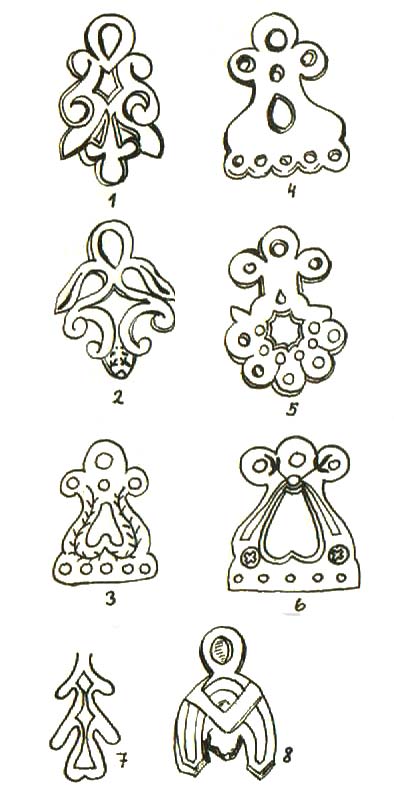

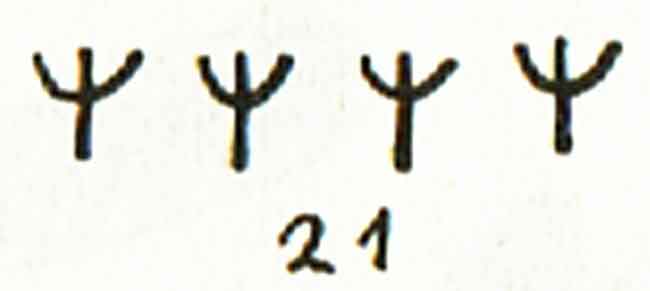

| The Yakuts are known to call these patterns “crest ornaments”, “tarax”, “oju” and “rydh”. (Panel I, fig. 1 through 4 on kumys containters, carved in wood). This crest had been used in China and Europe in association with female fertility, as is the case with the cowry and the triangle. In India, there are links to the fertility goddess called “Yoni”, who carries a crest as a symbol originating in the times of the Arian immigration. “Rydh” is also found in previous ethnic customs: “The crest is put underneath the butter cup to shield the evil eye.” Typically, symbols of fertility like this one have developed into signs of defensive charms, such as talismans or the phalluses put on children in Italy or Spain. It is striking how many rules and customs relating to pregnancy and birth found in the old world are associated with crests. There is no doubt that the crest was viewed as a symbol of fertility. |

|

|

|

|

|

The spring feast was celebrated in order to increase the fertility in the year to come. In contrast, at the autumn feast offerings were made to gain protection against the evil spirits.

| A different version of this pattern, the “spine ornament”, also known as “nail ridge”, “tynyraxtax torduja”, was found mainly on pottery but is not directly related to the crest ornament (panel I, fig. 8, kumys container, wood). |

|

|

|

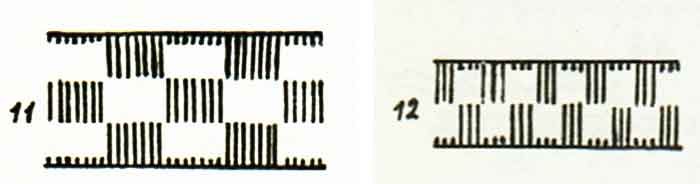

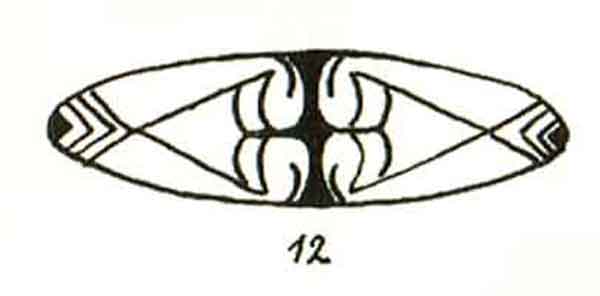

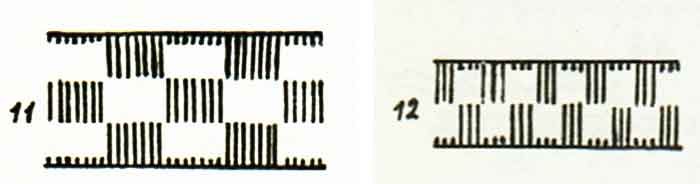

The chessboard: another ornament found mainly on kumys containers (panel I, fig. 11, carved in wood, and 12, wood, chip carving).. |

|

|

|

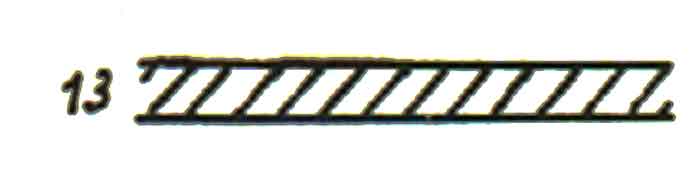

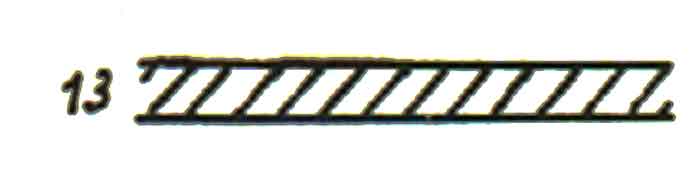

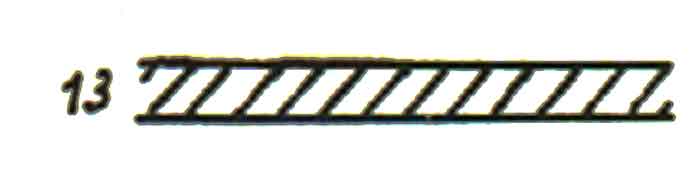

The rope sign: The strokes can run angular to the borderlines, they were used for all techniques. The sign was called “ärijä oju”, meaning: “wound ornament” (panel I, 13, on a kumys container, wood, chip carving). |

|

|

|

|

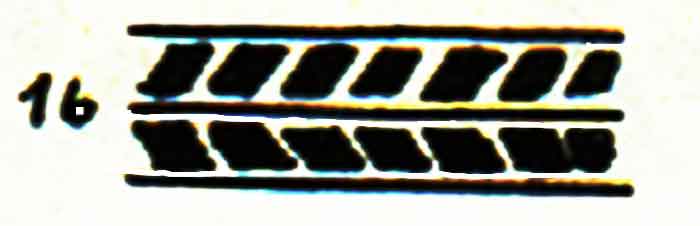

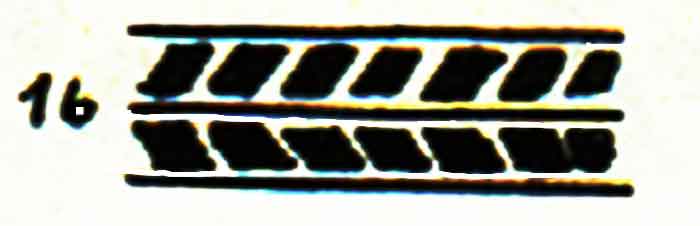

Fir-tree ornament: A very common version is the parallel run of two rope signs. It appears as early as in finds from Noin Ula and at the Yenisei, as well as in Kyrgyz finds from the 6th through 8th centuries AD (panel I, fig. 16 on a kumys container, wood, chip carving). |

|

|

|

|

| It also appeared associated with the Voguls, who called it “saune kur”, which translates as “magpie leg”. This pattern did not appear on kumys containers, only on silver manufacturing. |

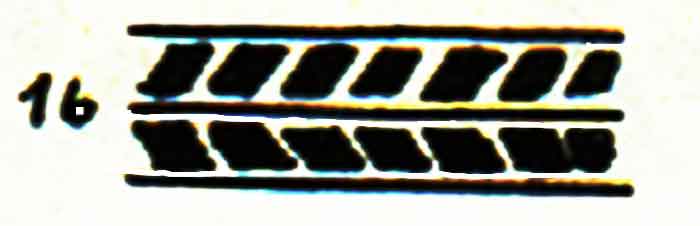

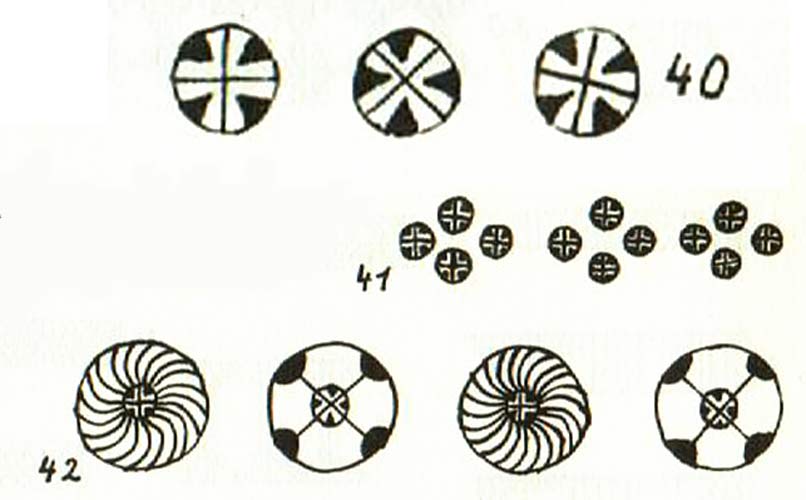

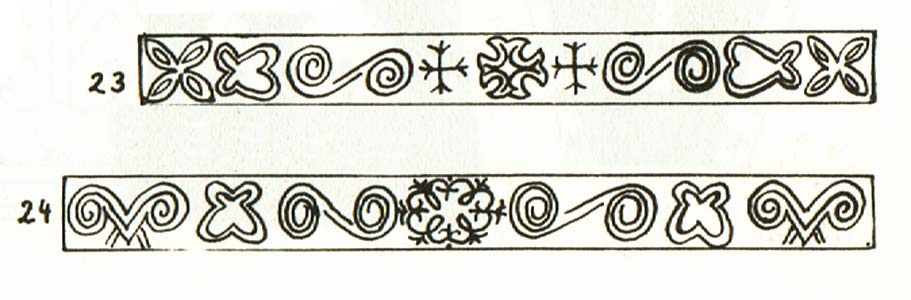

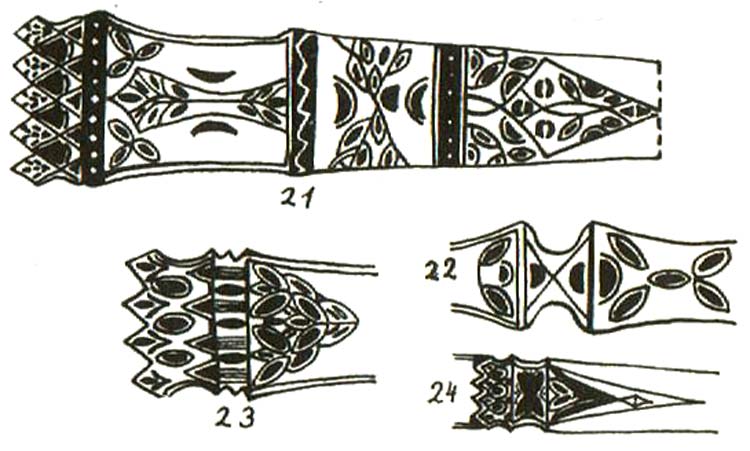

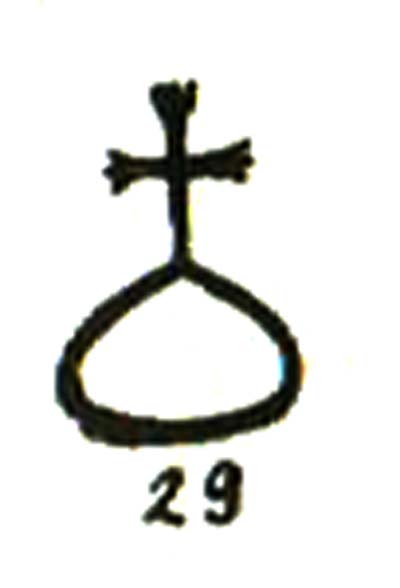

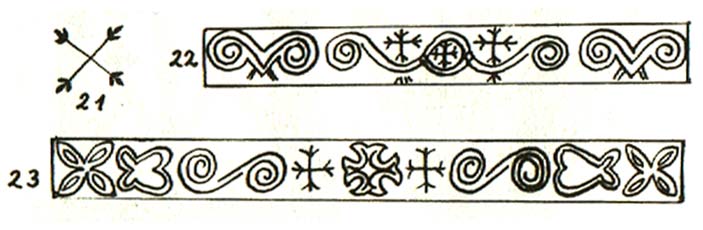

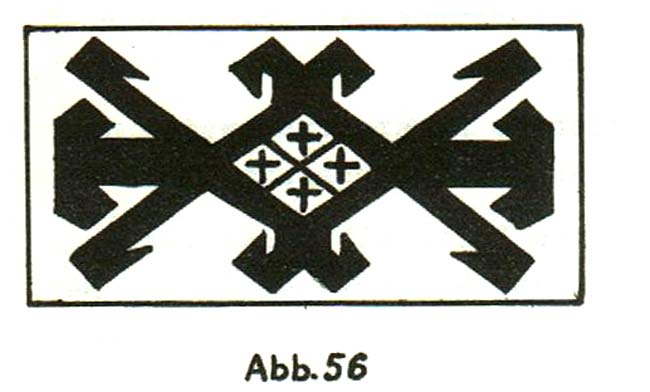

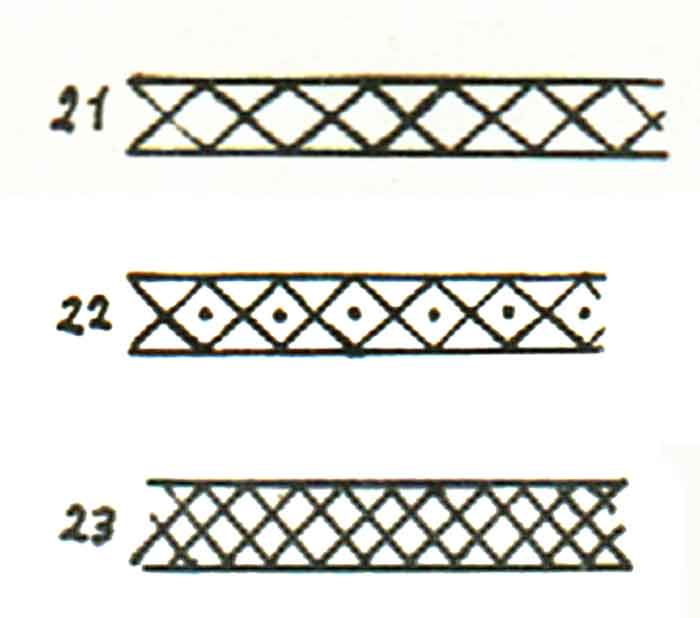

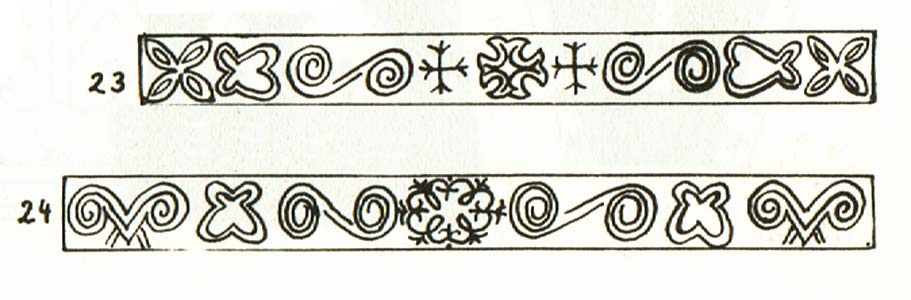

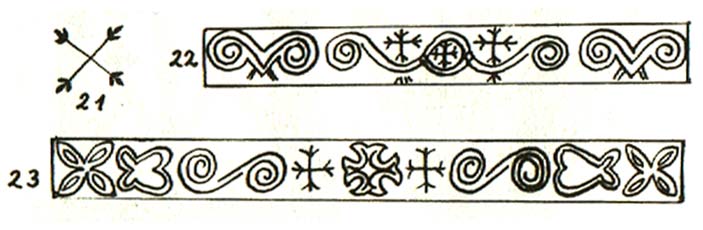

| Crosses: Though the erect cross often appears in connection with other motifs, it is hardly found as an individual motif as part of a serial ornament. In contrast, it is one of the oldest motifs of the Buryats. St. Andrew’s crosses are often found on kumys containers, compiled to one row; “ilim xaraha”, the net ornament (panel I, fig. 21, wood, chip carving). A spot at each center between two crosses was a means of depicting a fish (panel I, fig. 22, wood, chip carving). When the St. Andrew’s crosses are doubled in number and placed very close to one another, thus effectively overlapping, this pattern is obtained, just like in herringbone and satin stitchings (panel I, fig. 23, scored into wood). |

|

|

| . |

|

|

|

| The ornamental cross motifs have no connection whatsoever to the Christian cross. |

|

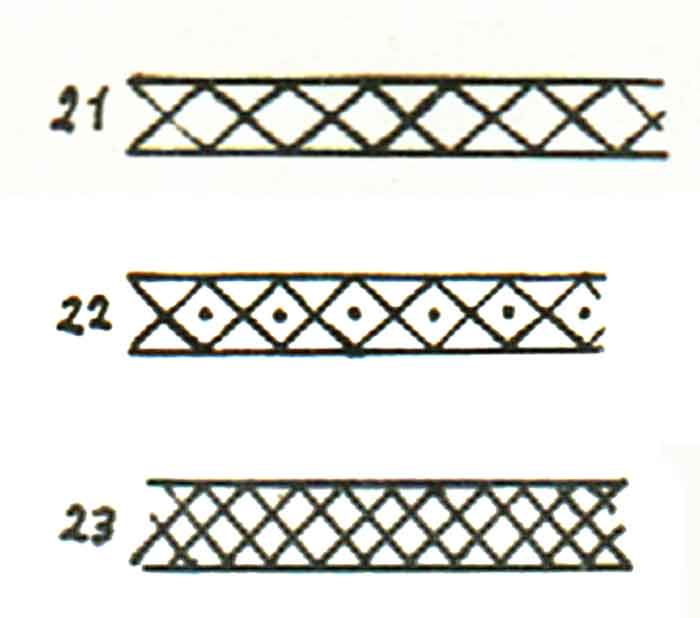

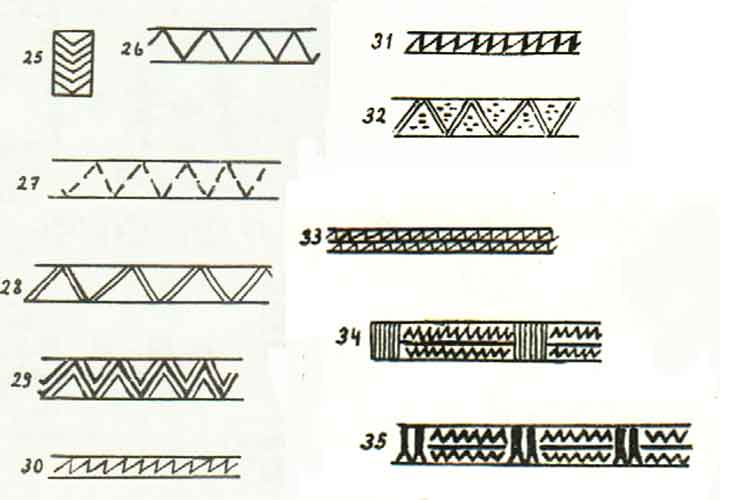

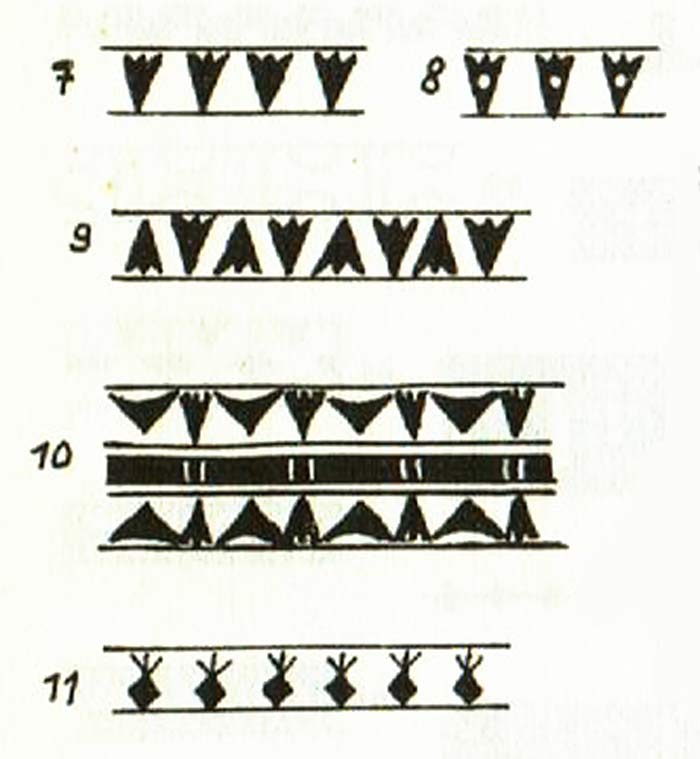

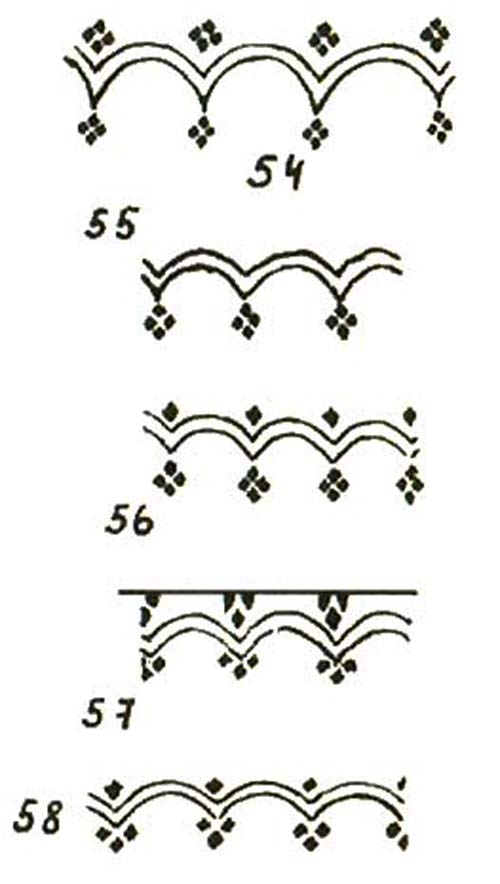

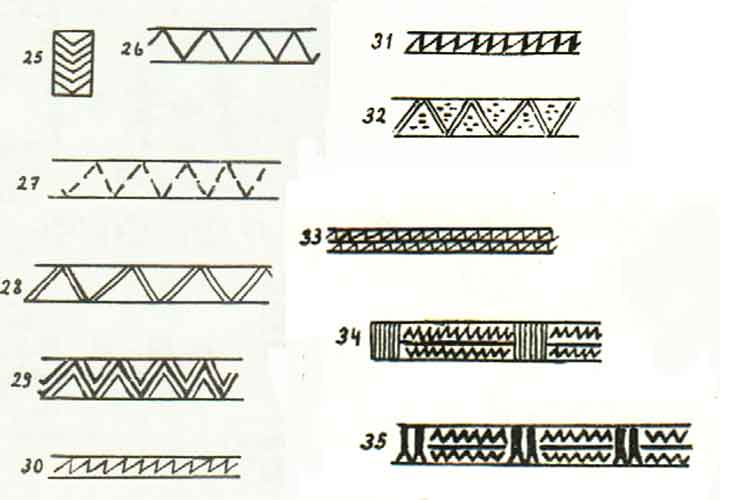

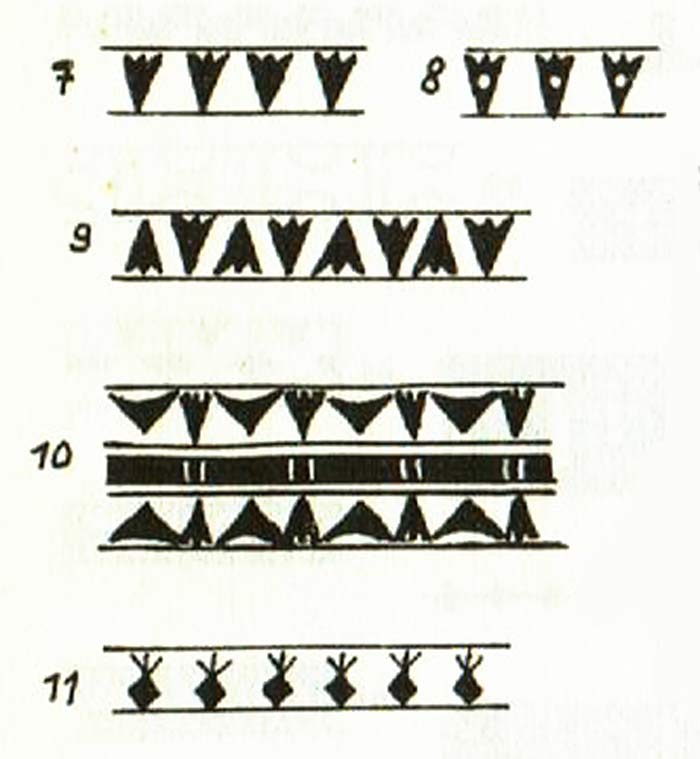

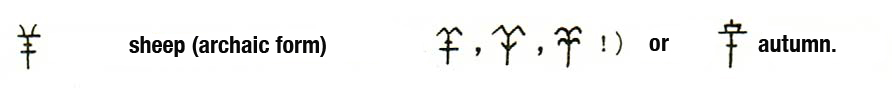

Zigzag and triangles: This is probably one of the most popular geometric serial ornaments. It is called “uasa oju” and depicts the large, conical Yakut summer tents on a kumys container. Another name they use for it is “biä miä oju”: mares’ teat pattern. Depictions of breasts are a globally common symbol of fertility and thriving. The Kets (Ostyaks) have yet a different name for this motif: “shadow of the yurt”.

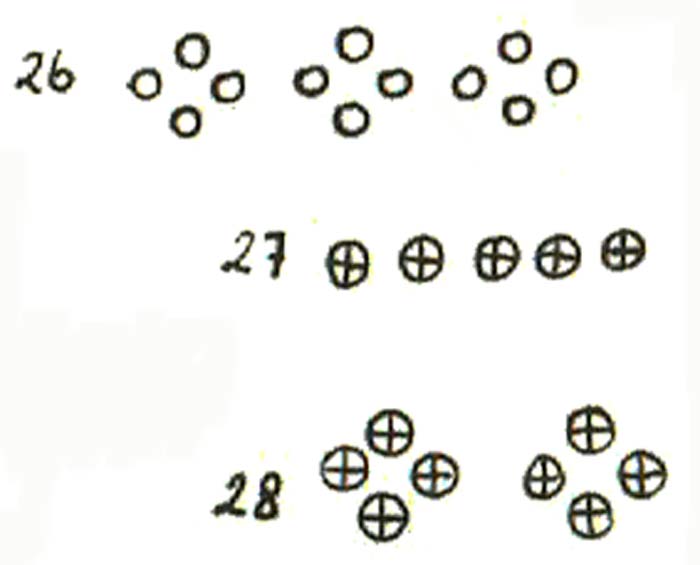

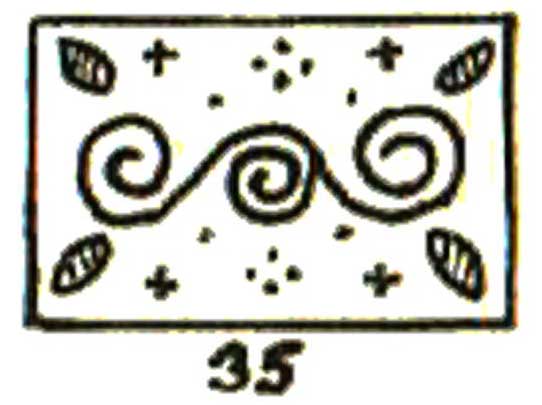

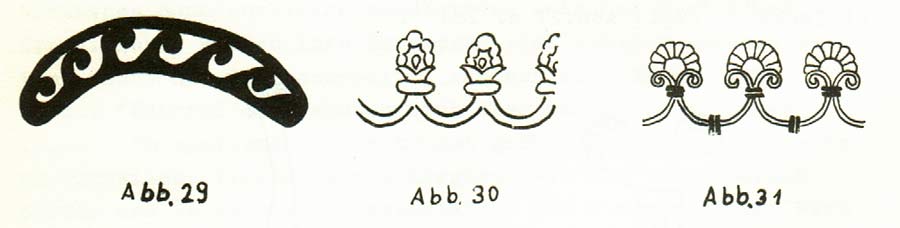

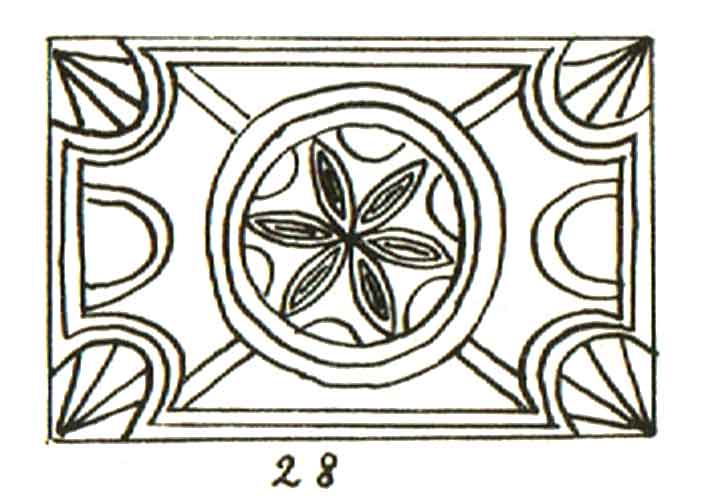

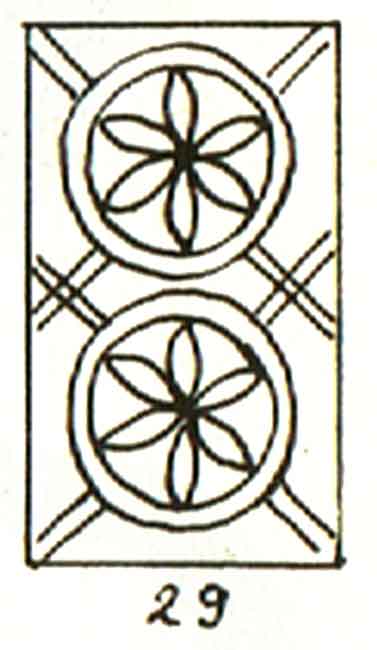

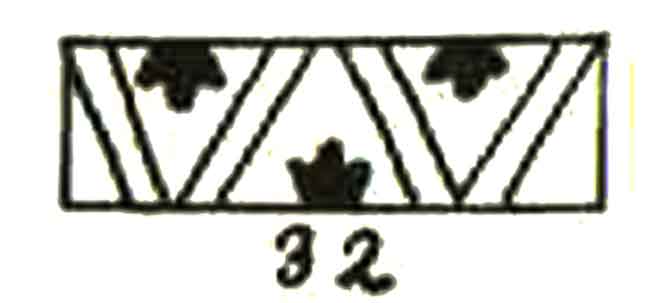

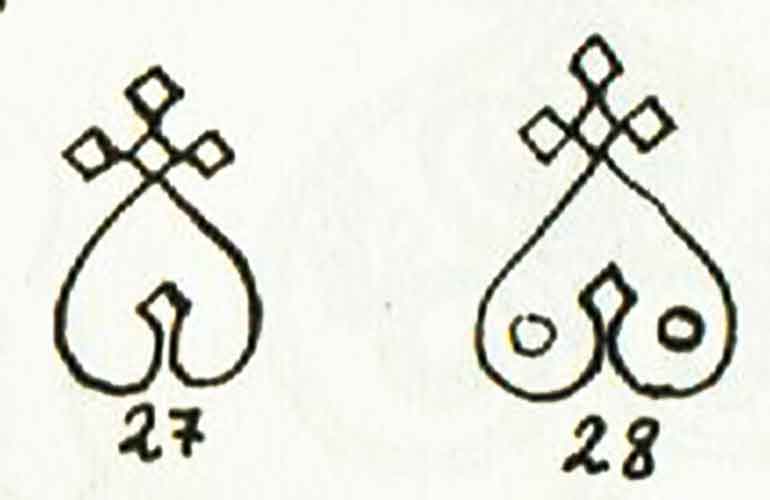

(Panel I, 25 through 35) zigzag lines: ornaments continung perpendicularly in disrupted sequence (fig. 27, kumys container, wood) in the form of overlapping angles (figs. 28 and 29, pot, modelled clay).

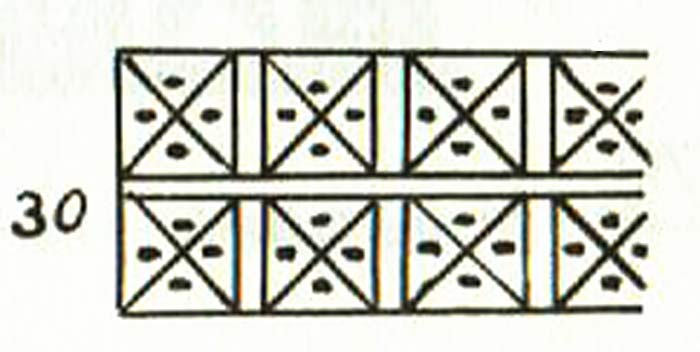

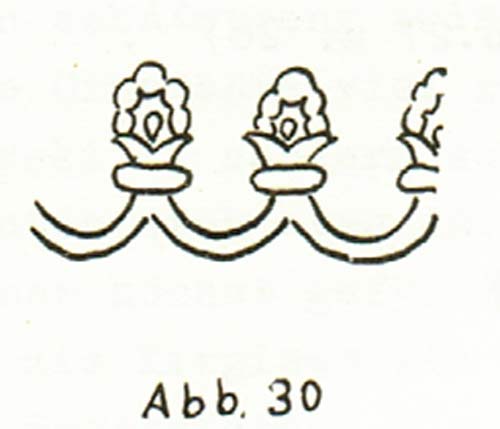

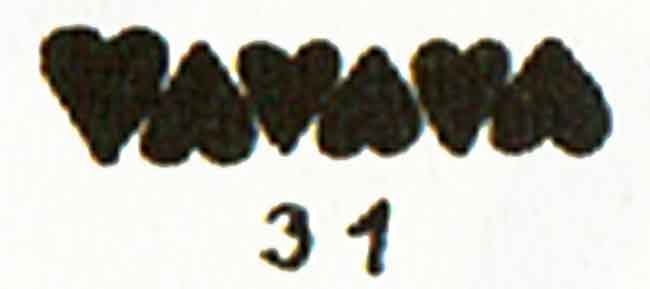

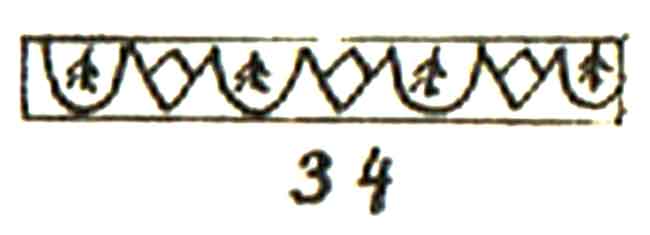

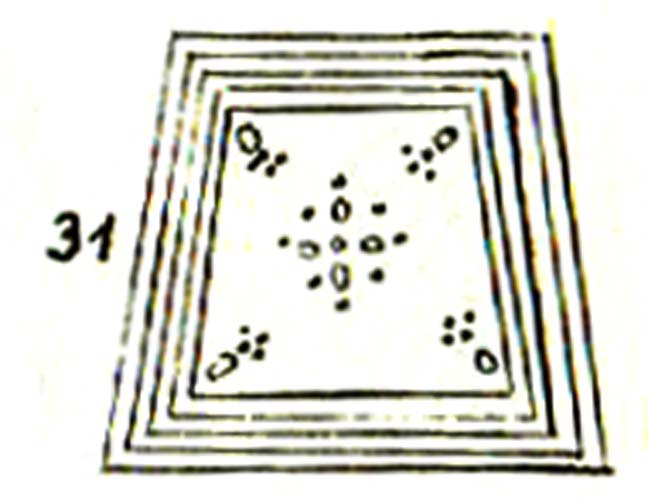

The basis of the zigzag patterns were triangles whose bases alternately rest on the top and bottom band lines. A nail ornament (fig. 30, kumys container, wood, chip carving, and 31, can, scored into wood) represents fingernails. Normally such patterns are the result of a potter pressing her fingernails into the soft clay.

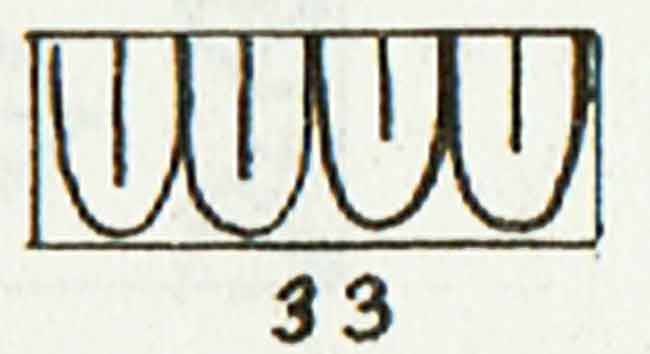

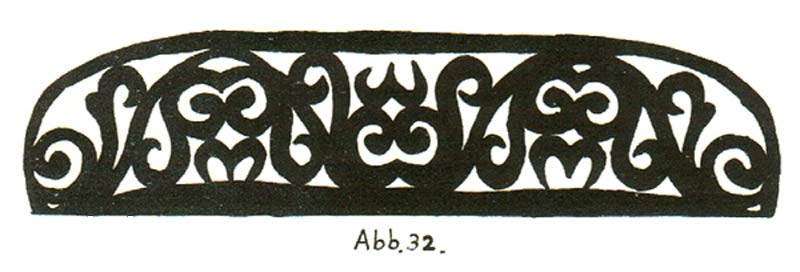

“Kärdis oju”, carved ornament (fig. 33, kumys container, wood, chip carving): Its appearance is similar to that of dents made in branches as memory aids.

|

|

zigzag lines

|

| The Buryats had similar shapes. |

|

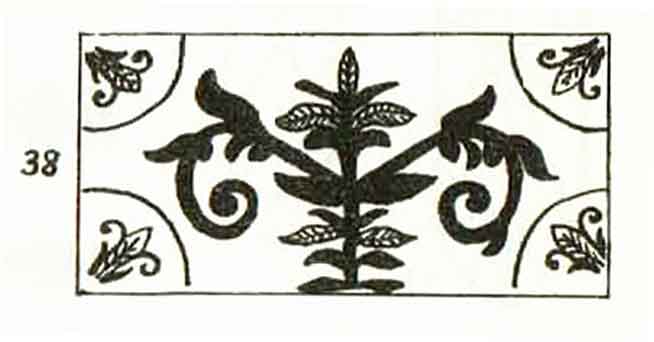

| In braiding or simple lacing works, however, the technological bondage of the zigzag pattern is clearly visible (panel I, fig. 38, kumys container, wood, chip carving). |

|

The zigzag ornament is one of the most common ornaments on kumys containers, not only for the Yakuts. It is just as common for the Paleosiberian peoples, the Buryats and other peoples of Southern Siberia. The Chukchi people see rivers in them, while the Chinese are known to draw mountains as zigzag lines. In pre-historic finds, the pattern of a triangle appears on ceramics from as early as the 3rd to 2nd millennia BC, and it also occurs in more recent finds, such as from the Pazyryk culture at the Altai and on ceramics of the Tagar culture.

|

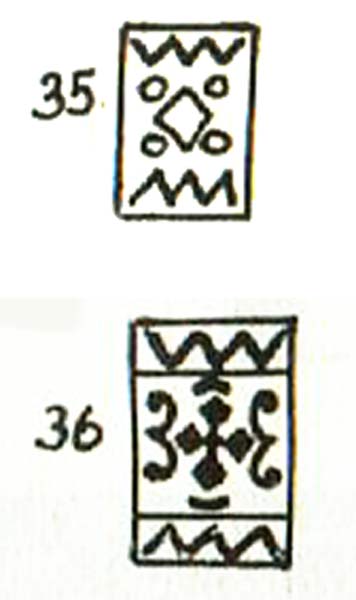

| The triangle is the only motif used in a serial ornament by simply putting several triangles in a row. (Panel I, fig. 36, chest jewelry, silver, engraved). The same was done by the Buryats, the Tungusic people, the Samoyedic people, the Kets (Ostyaks) and the Voguls. Sometimes a line of triangles suspended from the top edge of the pattern is placed opposite another line based on the bottom edge, with their tips almost touching (panel I, fig. 40, cup, bone, scored). |

|

|

A striking thing when comparing ceramic burial objects of early European and Chinese periods is that they were decorated with rows of triangles which resembled the Yakut pattern. As each death is associated with a rebirth, these triangles are related to the fertility symbol that represented womanhood. The Buryats are also familiar with this. These hobo signs indicate how many women live in a house. Similar examples are known from the Balkan and the Middle East, but these semantics were already known to the ancient Egyptians. It is striking that this motif very often appears together with the crest, which is also a symbol of fertility. This is also shown by examples from Indonesia, where the crest is decorated with triangular pattens in order to prevent disease. In India and China as well as in the Middle East, the triangle is a sign of womanhood. These patterns influenced Siberian peoples like the Yakuts. Among the Chuvashes, a Turkic people, graveposts were found that had such a triangle on it if a woman was buried beneath it. The other indentations represented their clothing. However, no one ever actually wore such triangles or zigzag patterns on their clothes.

An original meaning of these motifs cannot be interpreted with absolute certainty for the nomad peoples in Siberia, even though kumys containers produced for the spring feasts were decorated with such motifs. Other motifs were used, too, but they originated in the Chinese area and exhibited some similarities with those of the Indonesian population.

Triangle patterns decorated the pre-historical finds of Siberia at a very early time. In the closer and wider environment of today’s Yakutia, finds included applications among the finds from the Pazyryk culture at Altai and in the area around the southern end of Lake Baikal on ceramic products from the first centuries AD. Further west, in the Yenisei area at the time around the Nativity, these ornaments appeared on wood and clay.

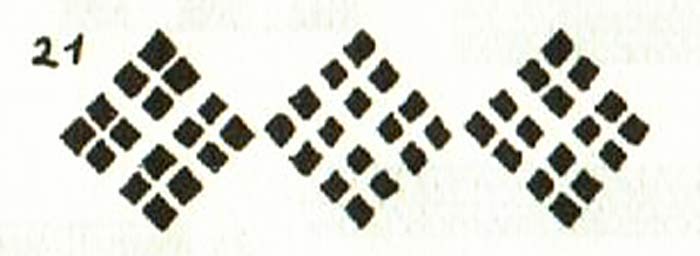

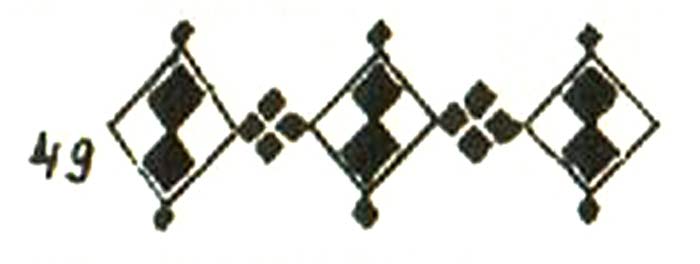

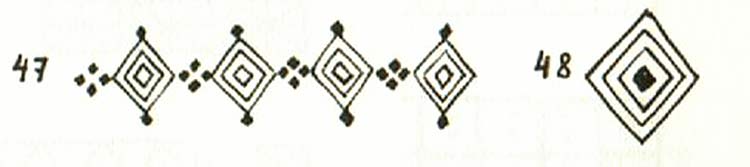

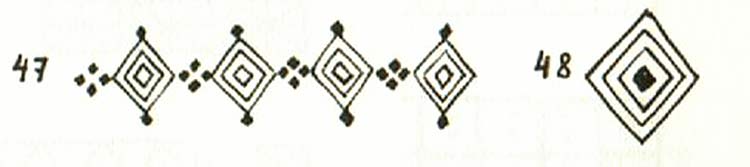

| Squares, rhombi and rectangles: A square or rhombus can originate from a triangle pattern (panel I, fig. 42, saddlecloth, cloth mosaic). |

|

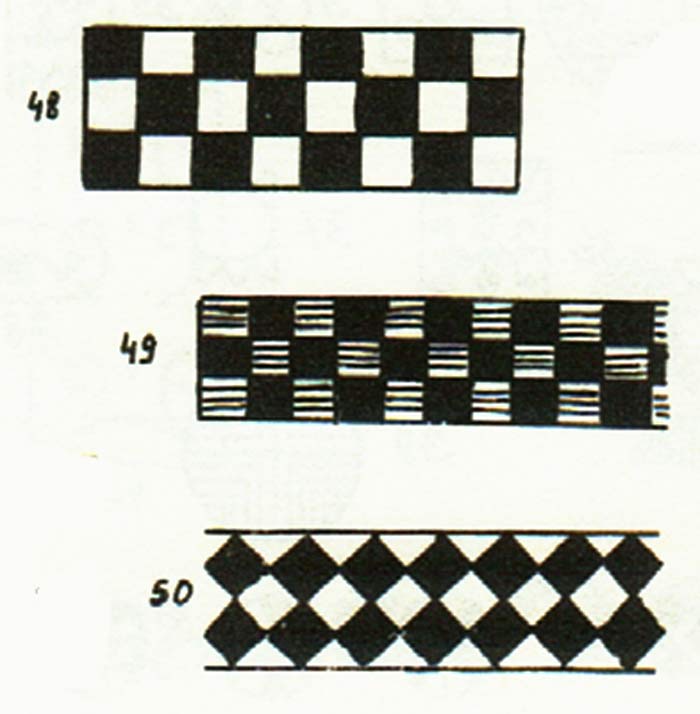

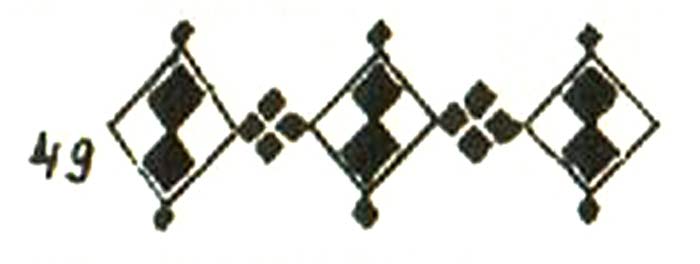

The use of squares or rectangles resting at one side is virtually limited to the chessboard pattern (panel I, fig. 48, knife handle, horn, immersed, 49, sewing box, wood, scored, and 50, carpet, fur mosaic). Patterns of this kind were found among all the neighboring peoples as well.

|

|

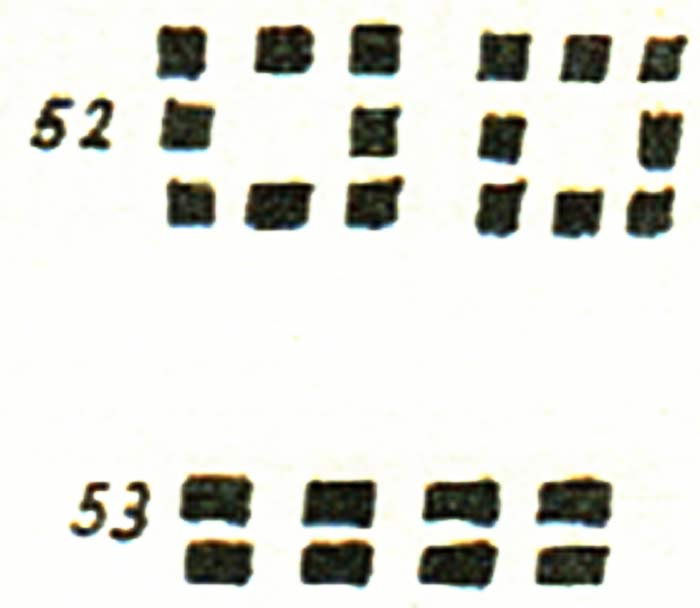

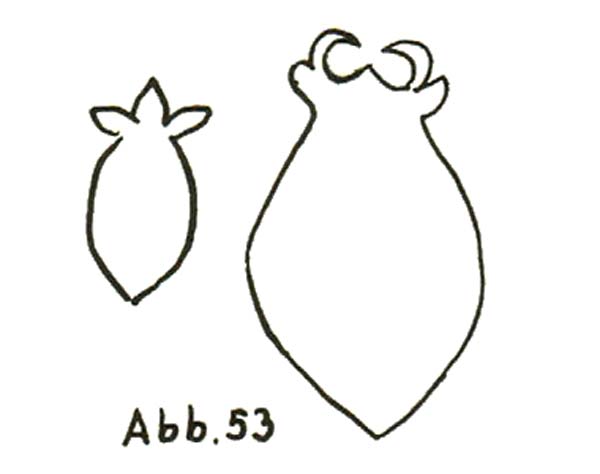

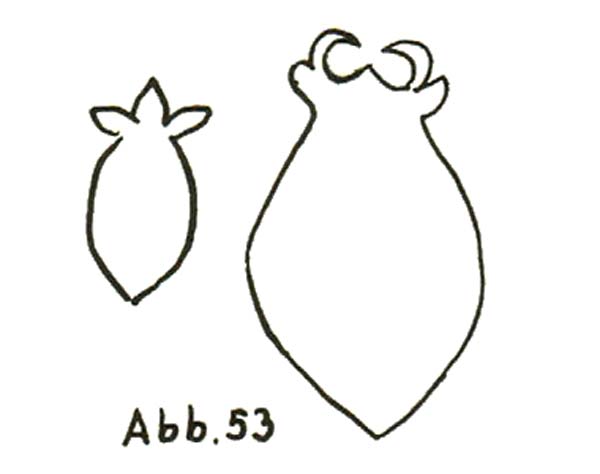

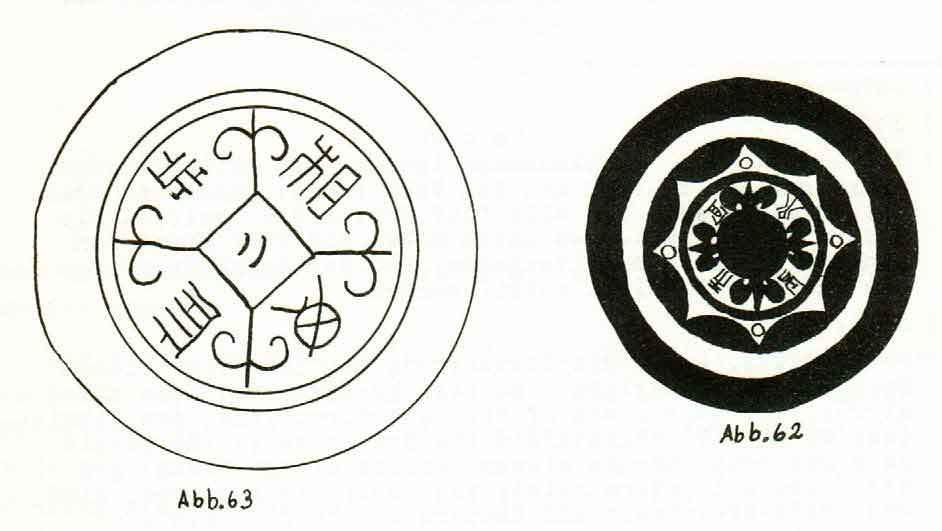

Two potter marks:

(Panel I, fig. 52, pot, stamped, and 53, potter mark, scored into wood).

|

|

|

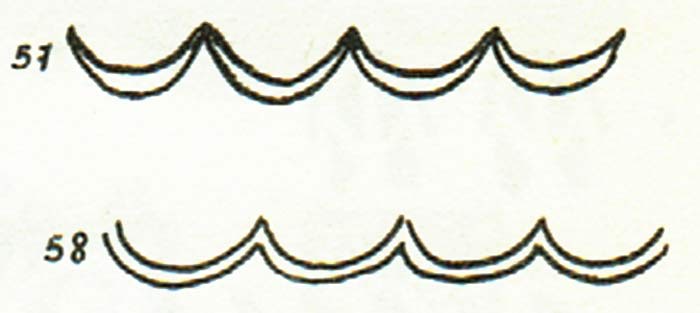

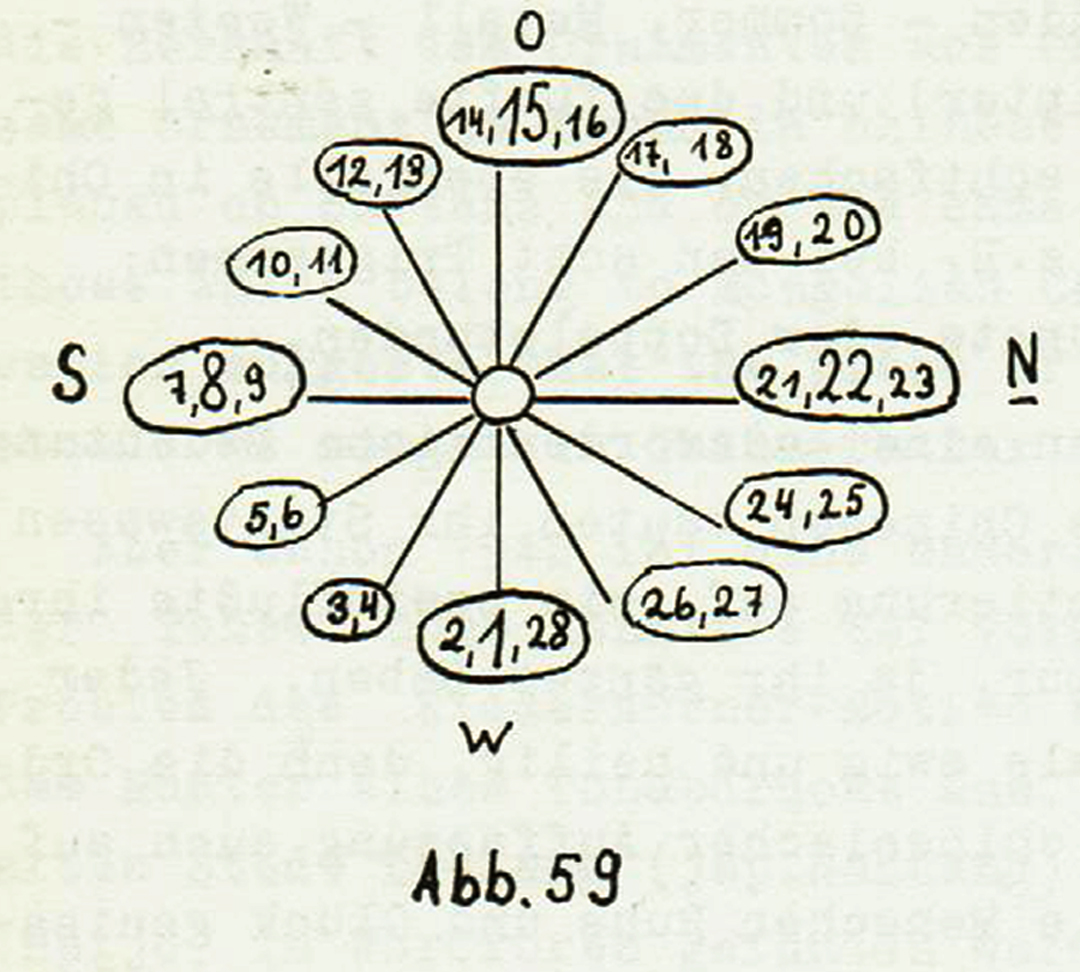

| Arches: The arch form can have various shapes. It can be flatter or more arched, or the baseline for the ornament in pottery and beadwork can be omitted (panel I, fig. 59, kumys container, wood, chip carving). |

|

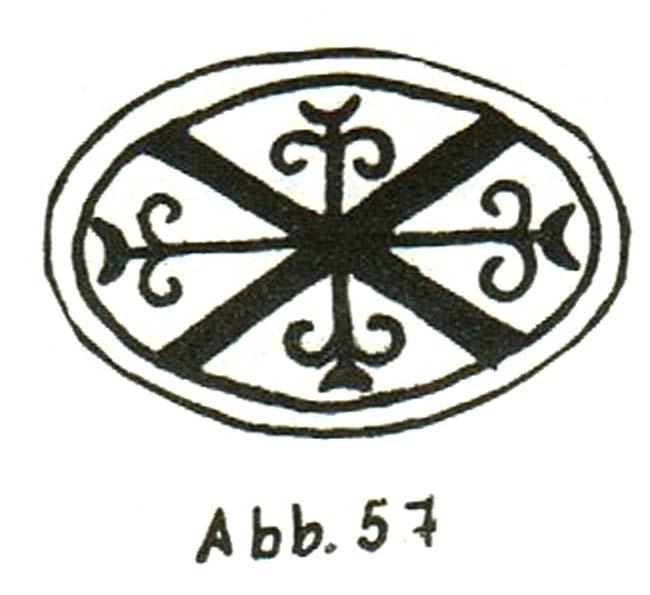

| The simplest version of this ornament is a doubling of the arch, where the two lines at the beginning and at the end either touch every single motif or run entirely separately (panel I, fig. 57, back jewelry, silver, engraved, and 58, sword, iron, engraved). |

|

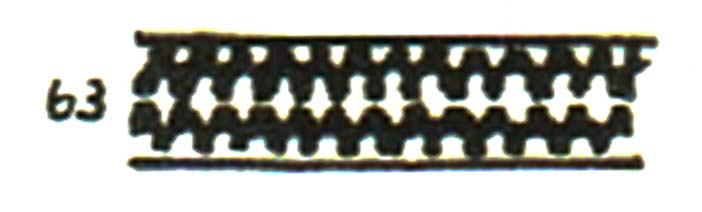

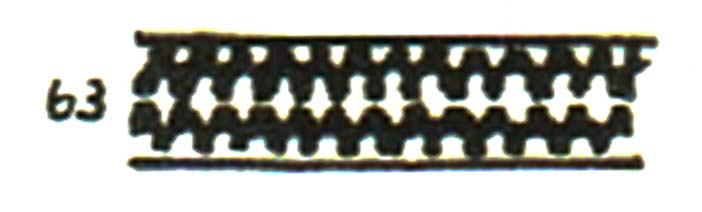

Yet another variant is created by adding arches in certain distances to top and bottom edge lines in a way that every single arch protrudes into the space between two of the other sides (panel I, fig. 59 or 63, kumys containers, wood, chip carving). .

|

|

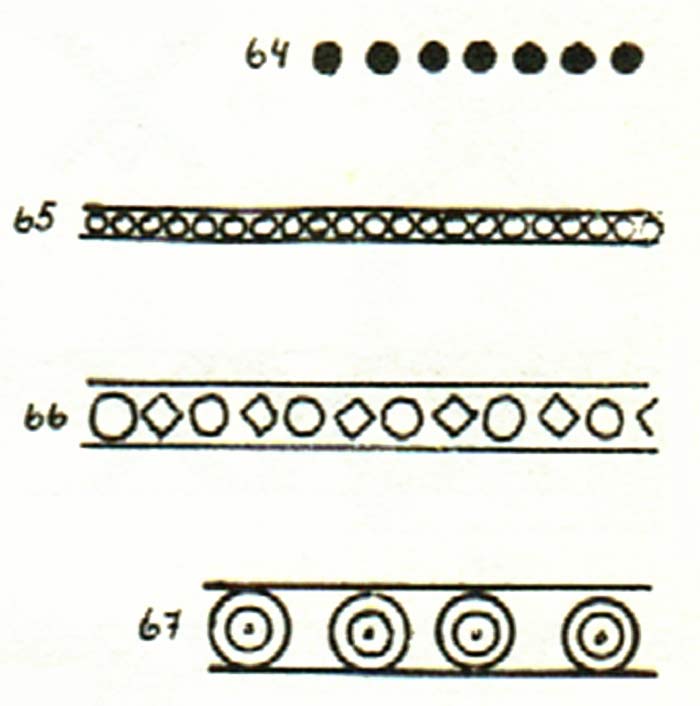

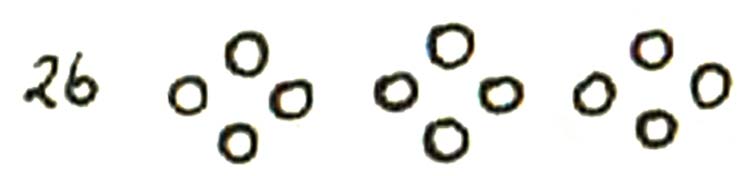

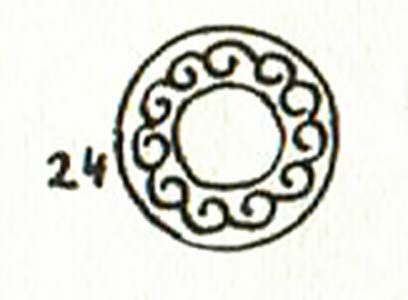

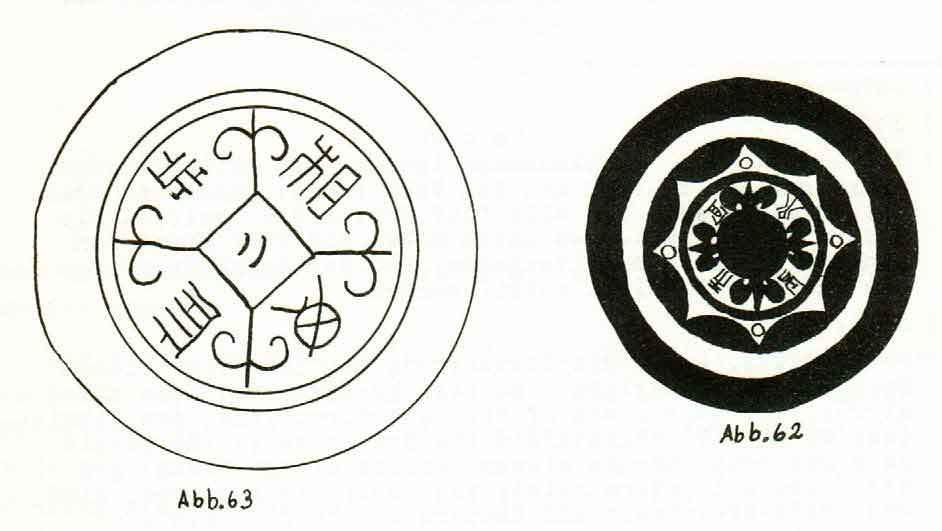

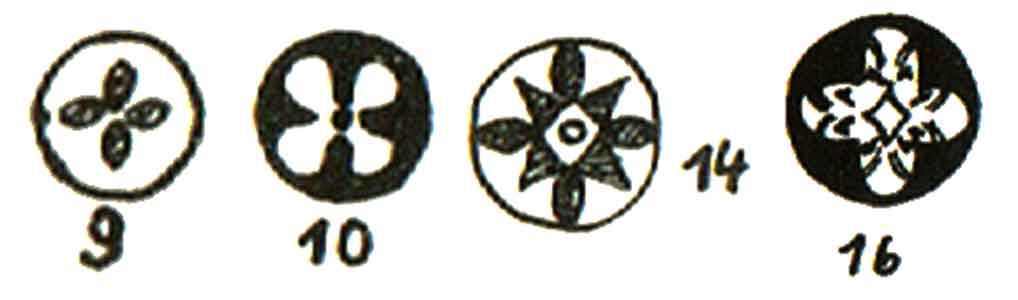

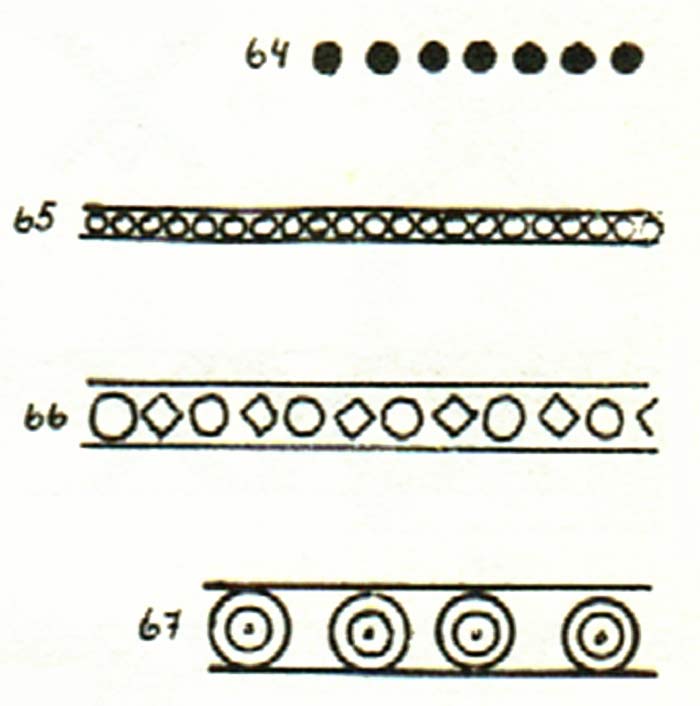

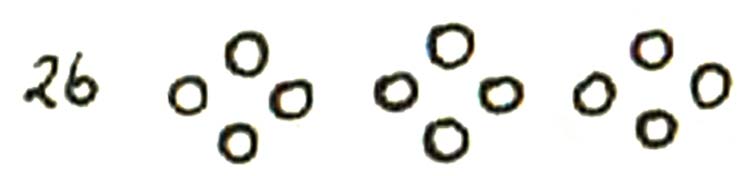

Circles and spots: Small circles like beads on a string border these patterns on silver. A row of circles was another popular mark ornament on pottery, named “türgüruk oju”, the “circular ornament” (panel I, fig. 64, pot, clay, stamped, and 65, decorative plate, silver, engraved). A difference between a circular pattern and a spot is that in the case of a spot the entire round area is impressed, not only the outer line. This is a pattern called “kövüör oju”, “kumys leather bag ornament” (panel I, fig. 66, kumys container, wood).

Yet another pattern (panel I, fig. 67, chest jewelry, silver, engraved) of several inscribed circles with a spot in their center. It was used by the Buryats and the Tungusic people as well. The same ornament is found with the Kets. For the Chukchi people, circles represented stars, while the sun was depicted by a much larger number of inscribed circles. On Buryat drawings, the sun is depicted in the form of 8 or 9 inscripted circles. To the Kyrgyz, a round disk means “new moon”. As explained by descriptions from China, these circles with a spot represented the “Eye of the Sun”. |

|

|

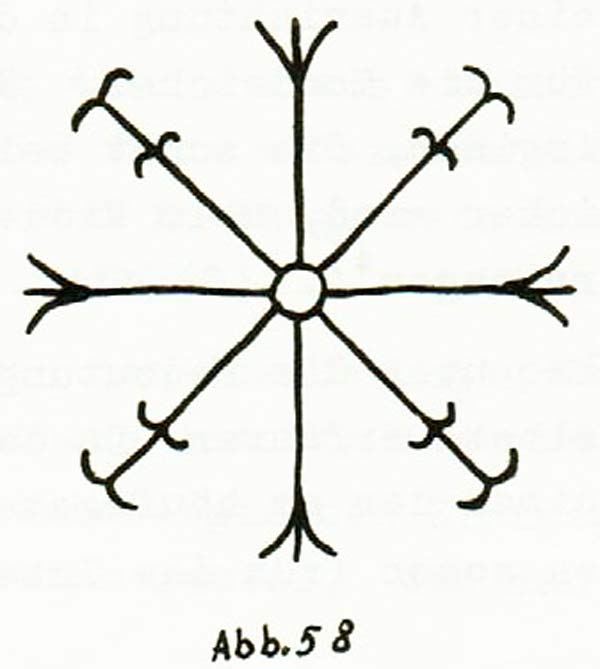

The Yakuts depicted the sun on the dresses of black shamans in the form a disk that had a small hole in its center. However, this symbol resembles the image of the Earth on the same costume. On ornaments whose meaning is known the sun ist symbolized in a different form, as will be explained below.

|

- Find more information on depictions of the Sun below in „Sun-sign Representations“

|

The Yakuts are comprised of two immigrated tribes, one of which arrived approx. 1000 years ago, while the other had already been resident for some time. Thus, it is perfectly plausible that the Yakuts, just like the Buryats, had two different types of sun representations. Sometimes they drew the sun as a curled shape, like the Altaians, the Kyrgyz and other Southern Siberian peoples do, and sometimes they expressed it by two or more concentric circles. For example, the round and shiny decorative disks women wore on their hats or above their coats that were decorated with concentric circles or concentrically designed patterned stripes were referred to as “the sun”. This is why, whenever women perform ceremonies men are not allowed to watch, they turn their hats around so that the disk looks rearwards, because the Yakuts imagine the sun to be male. These disks are also found riveted onto kumys containers. This form of depicting the sun was also common with the Chukchi people, the Koryaks and – judging from their shamans’ jewelry – the Yukaghirs.

A few motifs of this group are classified as rare basic motifs which are only rarely combined with others..

|

| The relief ornament: This ornament resembles the pinnacles of a tower. It is found exclusively on kumys containers, and the Yakuts call it relief ornament, or “tomtoryo oju” (panel I, fig. 68, wood, chip carving).. |

|

|

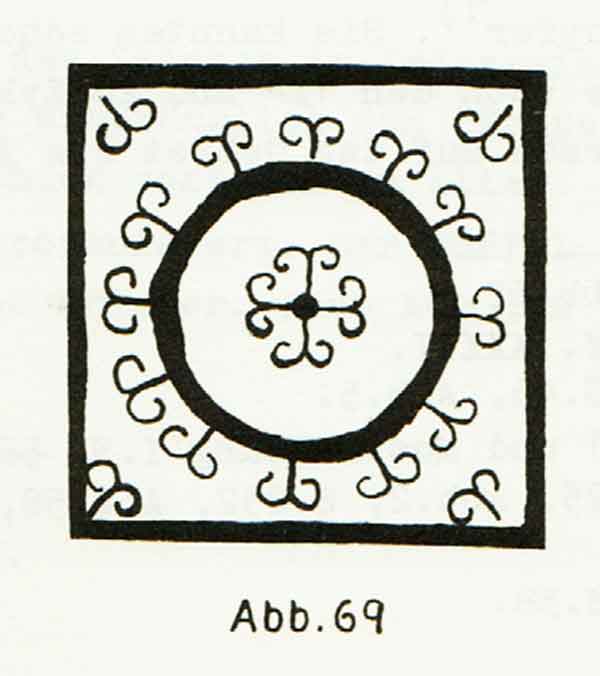

| The wedge motif: In this case a motif is simply wedged between two edges. Its appearance resembles a wedge for cleaving wood and is referred to as “kybyta oju” (wedge ornament) (panel I, fig. 69, kumys container, wood, chip carving). |

|

|

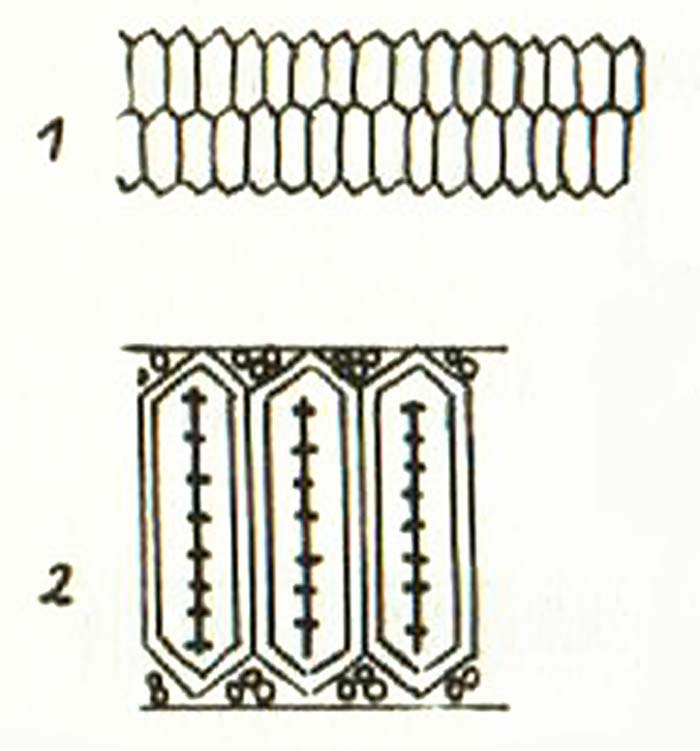

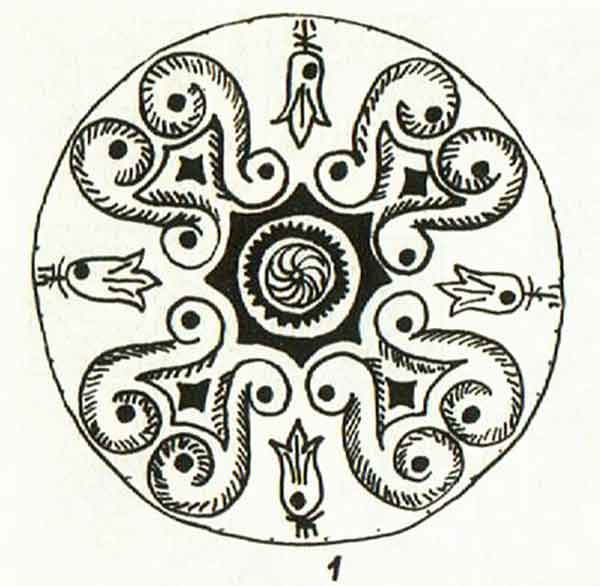

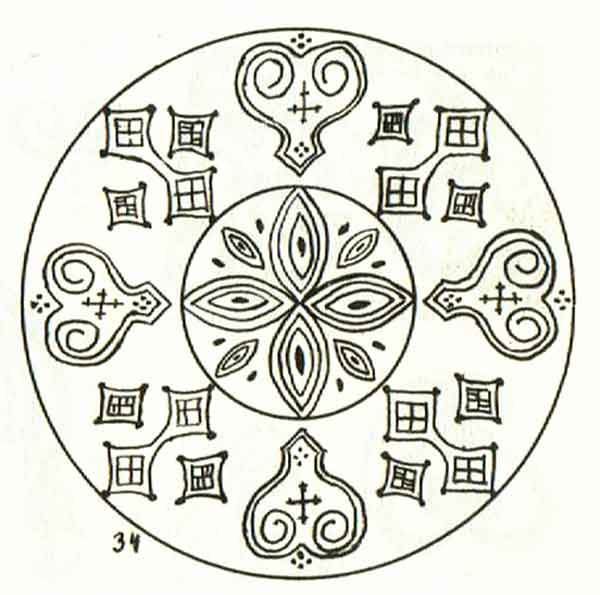

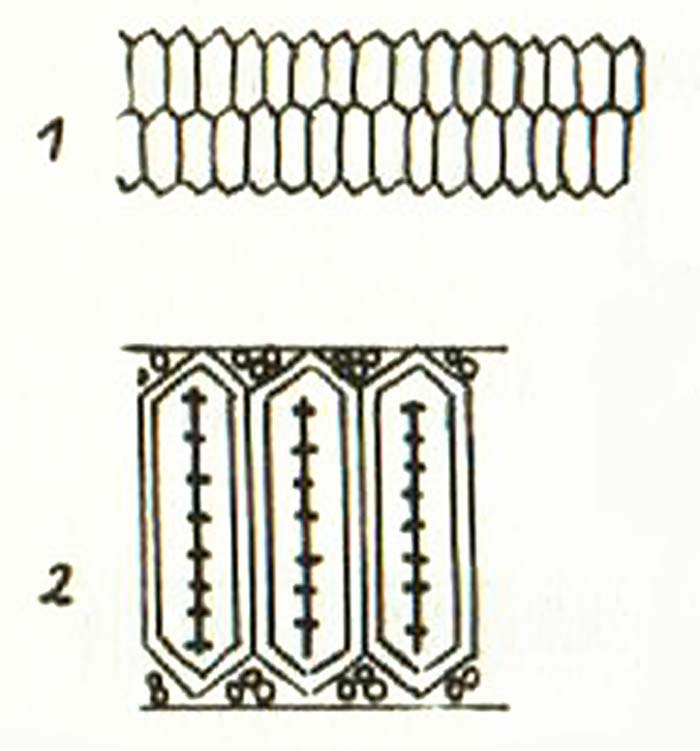

| The finger ornament: The pattern consists of hexagonal cells, which are arranged like honeycomb in a hive. Its name is “tarbax oju”, finger ornament (panel II, fig. 1, kumys container, wood, and 2, bead, tin, engraved). |

|

|

Silver stamp and pottery stamp: One of the stamps for silver ornaments has a near-triangular shape, with the exception that the base is not linear but has jags. A circular line is impinged in order to border an adjacent ornament, or it is impressed in a straight line. This pattern often alternates between the tip indicating upwards and downwards. Very often, a spot is omitted in the center of the triangle (panel II, fig. 7, shoe on male belt, silver, stamped, 8, decorative plate, silver, engraved, 9, shoe on horse halter, brass, stamped, 10, scoop for kumys, wood, chip carving, and 11, decorative plate, bronze, stamped).

|

|

|

Ornaments of this group were stamped on pottery. A two-jagged cane is used to impress them mostly into the coils of the pots. This motif is aptly called “bytasyt zamyta”, “the mouse walked” (panel II, fig. 3, pot, clay, stamped). Other ornaments also resemble trails of animals (panel II, figs. 4 and 5, potter mark, wood, carved).

|

|

|

|

The most common combinations in motifs are:

|

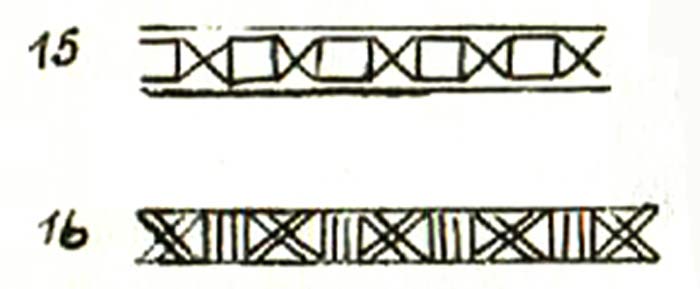

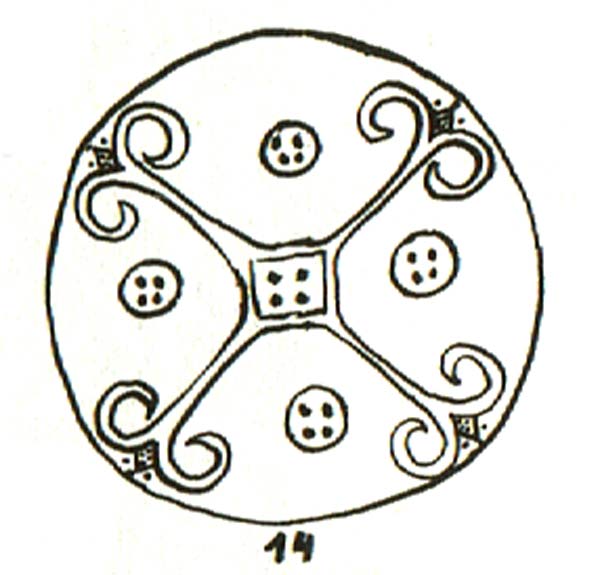

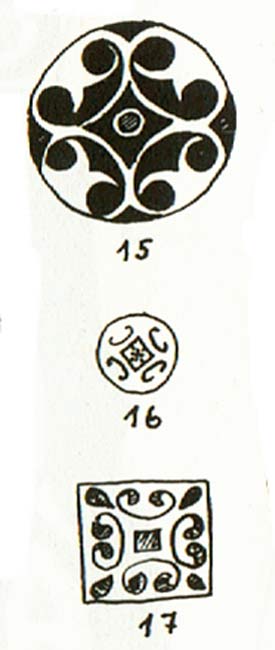

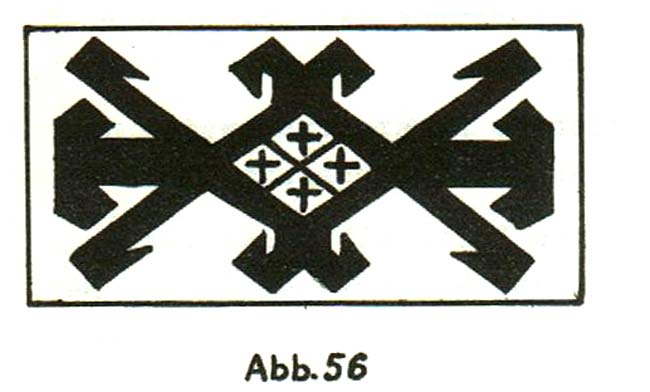

Cross figures: A minor change in the cross ornament is performed (panel II, fig. 14, tobacco box, scored into wood). These St. Andrew’s cross ornaments are identical to those of the Kets and the Buryats and serial ornaments very often shown on kumys containers (panel II, fig. 15, wood, chip carving).

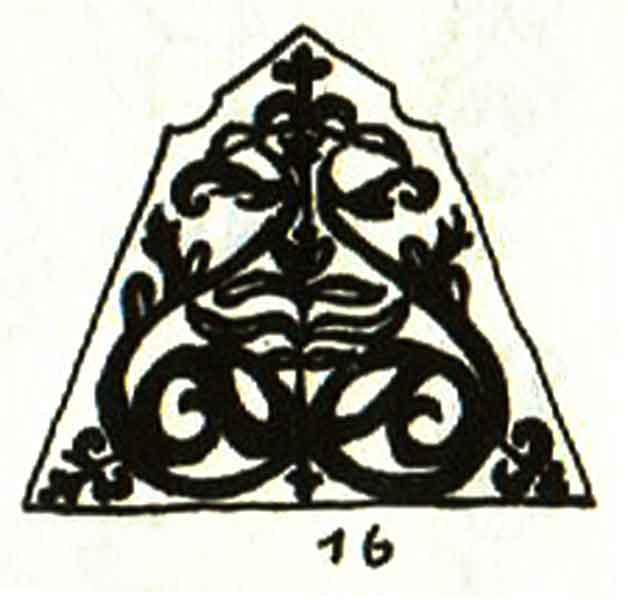

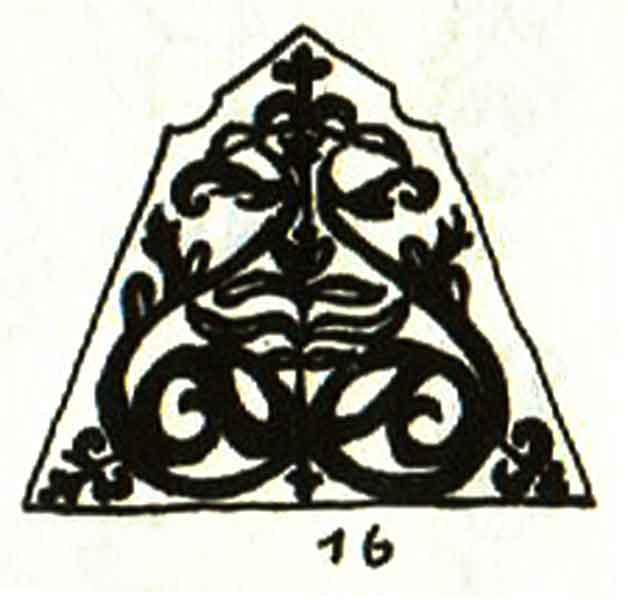

A kumys container (panel II, 16, scored into wood) has interesting parallels to a Hunnic caldron found in Hungary. On this caldron, St. Andrew’s crosses and crest ornaments alternate. |

|

|

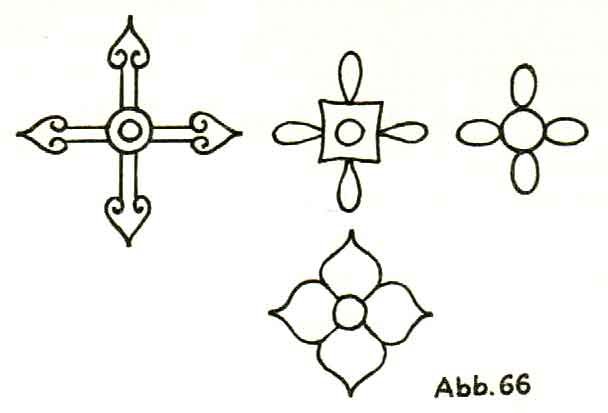

Among the Yakut ornaments, the plain cross in connection with circles or squares was very popular. These motifs occur on almost all kinds of everyday objects but not on silver.

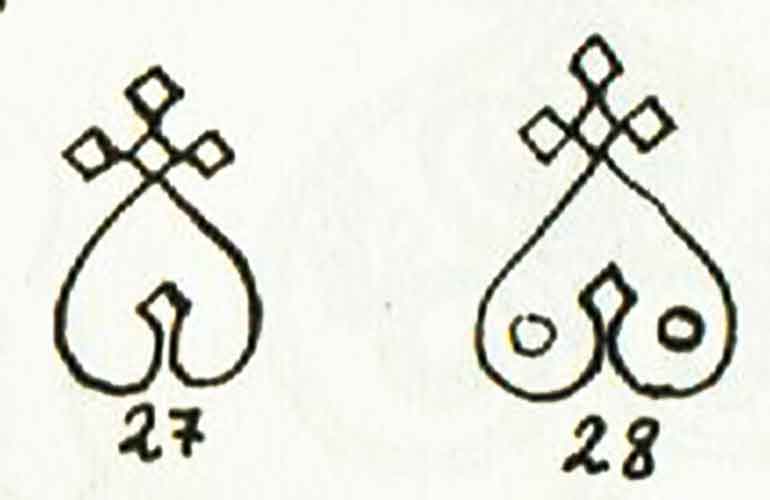

Both triangles and squares are arranged around a St. Andrew’s cross that cannot be seen in the pattern as such because it is left out between the squares and the triangles. Patterns of this kind were stamped onto pottery. When the potter stamps are impressed the circular line is almost indiscernible, and the base of the original pattern becomes an ornament again.

| Four of these triangles appear on ceramics with a round base (panel II, fig. 24, kumys container, scored into wood). They are called “bultavir torduja”, “rounded ridge". |

|

|

Very often the pattern itself is depicted, as is the case on small, non-ornamented, square decorative plates, which are overstitched crosswise with two stitches, on bilayered works, were this form is cut out and stitched onto a base with a different color, or on wood works.

The cross patterns are particularly common. They are among the few ornaments which are found equally on kumys containers and objects manufactered at home. The principle was familiar to the Yakuts, so it was already applied in plainer forms (panel II, fig. 26, potter mark, scored into wood; 27, pot, clay, stamped, and 28, can, birch bark, bilayered work).

|

|

|

There is a motif where four squares are put together to form a single square (panel II, fig. 21, shaman’s jewelry of a black shaman, iron, engraved).

|

|

|

On bilayered works, very often the cross and the four squares between the arms of the cross are depicted (panel II, fig. 31, box, birch bark, bilayered work).

|

|

|

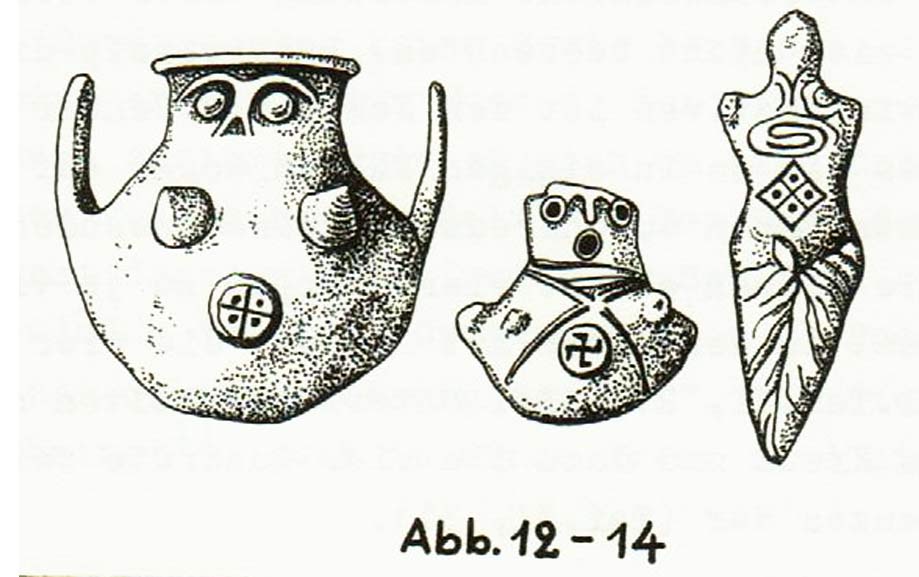

This pattern was found in Troya, for example, where it imitated female shapes. Instead of the genital, a swastika (an ancient Indian pattern, symbolizing the revolving sun) is applied on one of the urns, and a cross with four spots on another one (figs. 12 snd 13). On yet another square the swastika is found on a female shape from Romania (fig. 14).

|

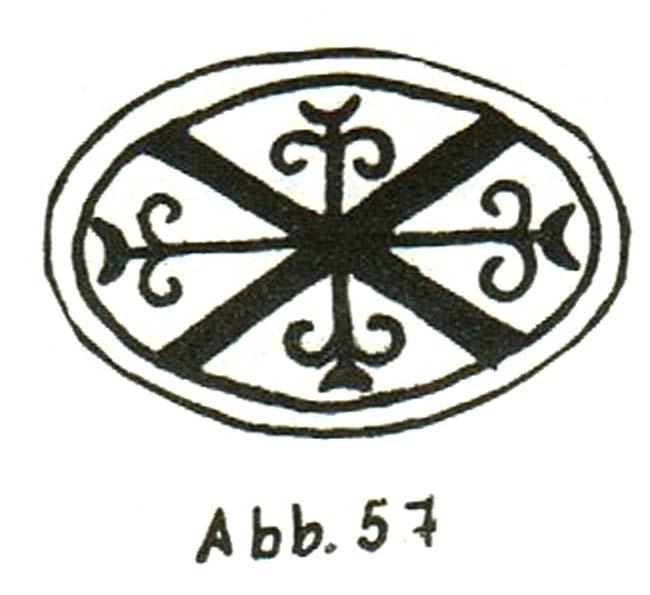

- Sun-sign Representations -

In Greece, the genital is also replaced by the swastika, a symbol of the sun. Wherever it occurs, it symbolizes the revolution of the sun and consequently, fertility and happiness.

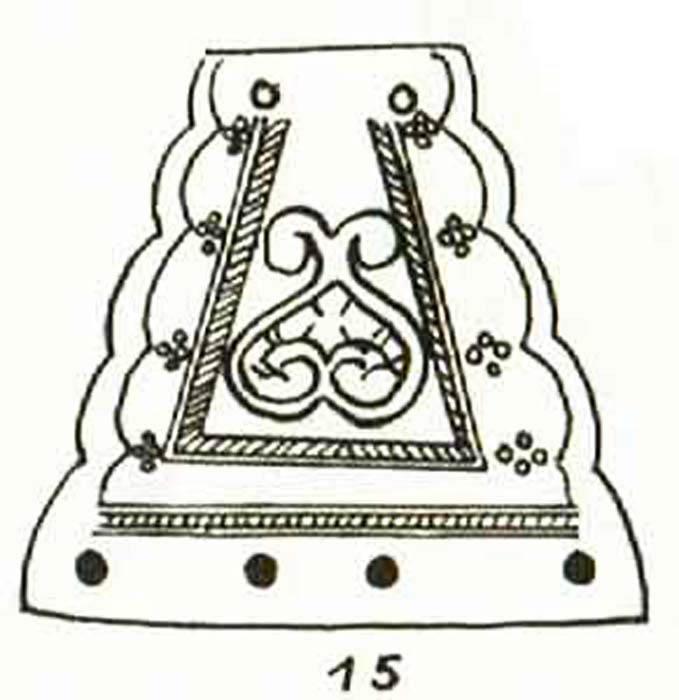

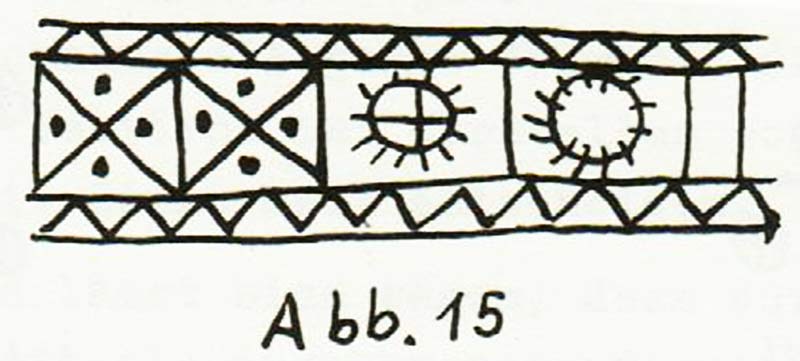

The meaning of the motif discussed herein has to be similar. The patterns on a shaman drum on which it decorates the edge between zigzag lines and depictions of stars (fig. 15) demonstrate that a certain meaning of this ornament for the Altai Turks, whose material culture and religion were similar to those of the Yakuts in many respects, was preserved until the previous century, at least as far as their belief in a sacred being is concerned.

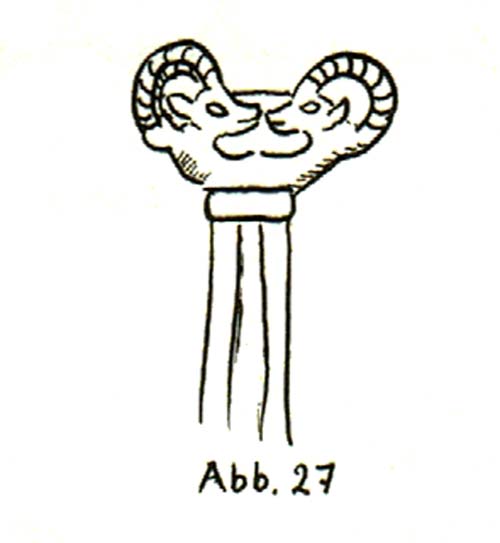

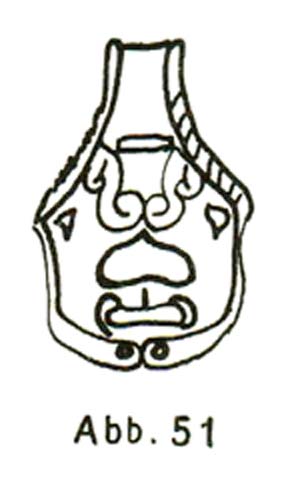

| This pattern is not very common in Yakut finds, appearing only on one can for wax candles (panel II, fig. 30, can, scored and carved into wood). Also, a ram-horn ornament was scored into the cap of the can, which must have had a cosmological meaning initially, and which was derived from China. The Buryats are familiar with this ornament, too, as revealed by finds from the upper Lena area. This shape is very old, as it was found belonging to the Pazyryk culture at the Altai. |

|

|

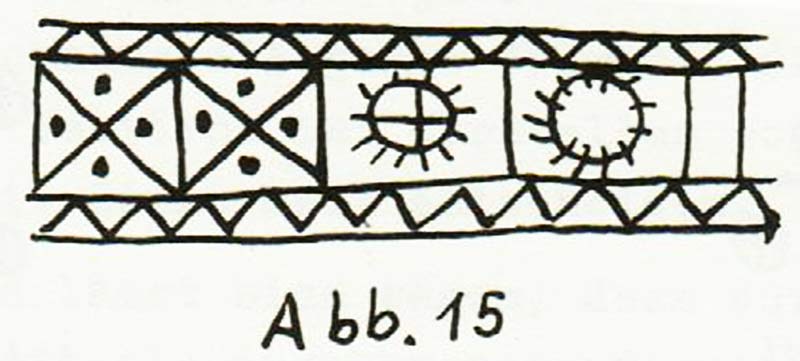

| Like with many other motifs, parallels to Chinese signs can be found here. The cross with the four spots appears on early Chinese ceramics, as does the crossed circle. A square crossed on half of its side represents the Chinese sign for “field”. The crossed circle is another very old sign. Repeated four times, it means thunder (fig. 16). It was considered a good sign because thunder usually appears after rain. |

|

|

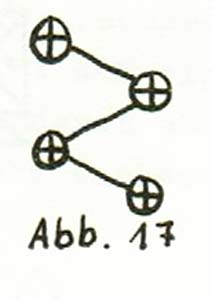

The sign is also associated with the zigzag of thunder (fig. 17). The resulting sign, however, is considered a sun wheel, which is also known to be associated with the crossed circle. These motifs are found in Indonesia as well. It is therefore not unusual for the shamans in North Asia to depict the sun as a wheel.

|

|

|

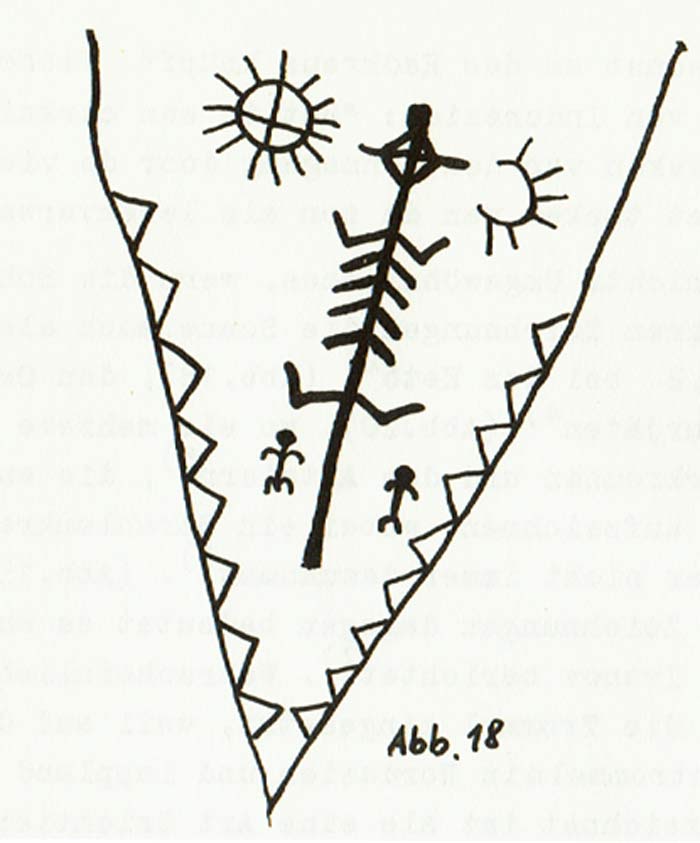

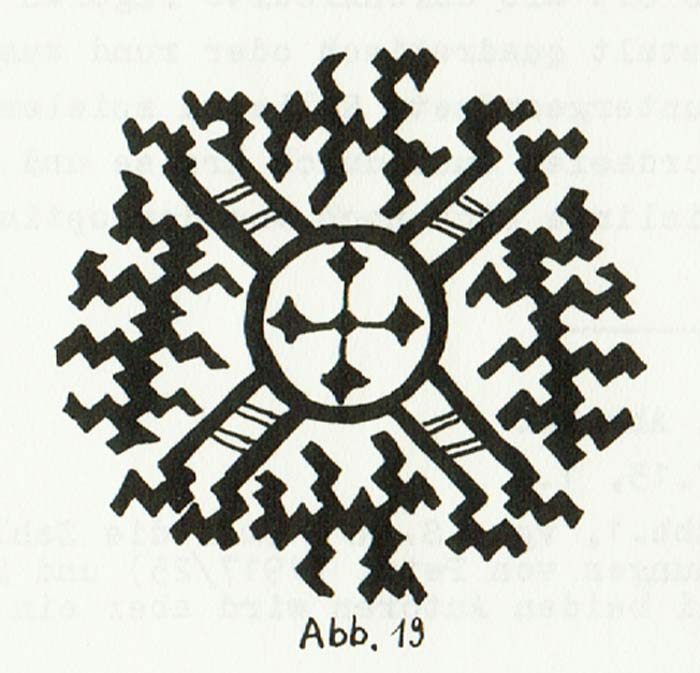

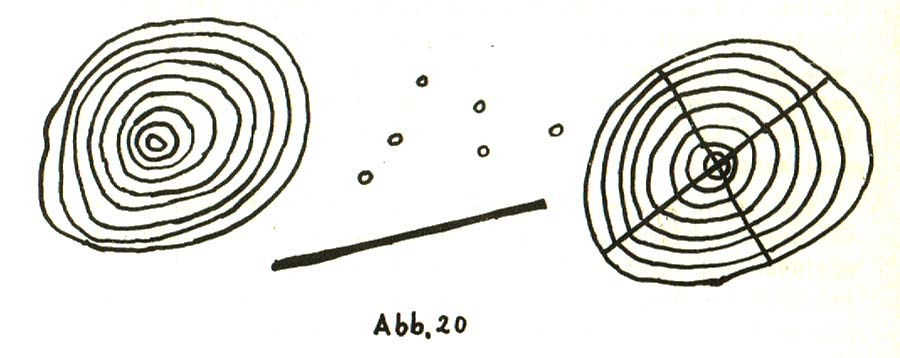

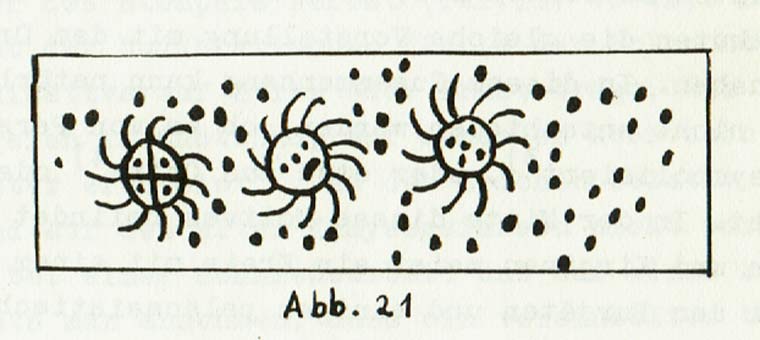

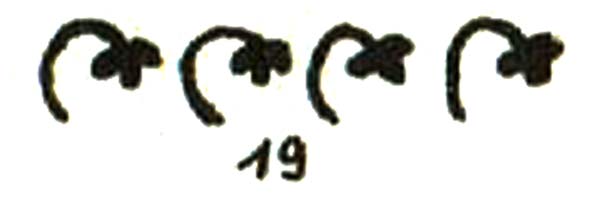

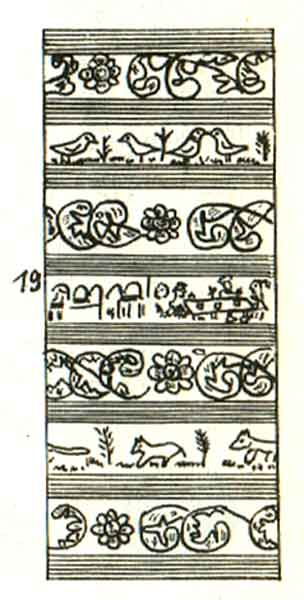

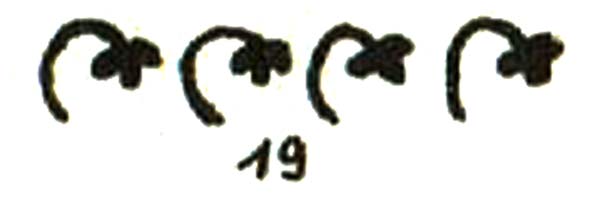

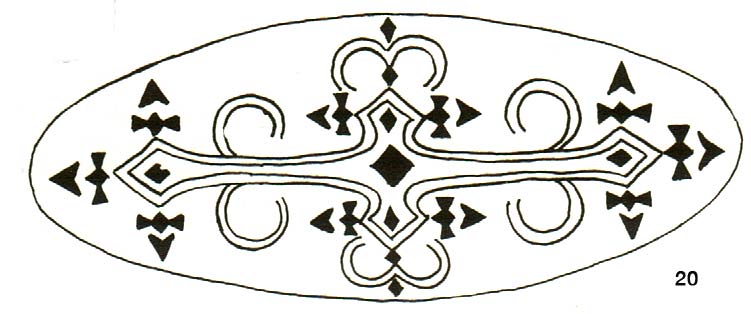

As well, as do the Kets (fig. 18 – the sun on the left, the moon on the right, and the shape of the shaman and two assistants at the centre on the back of a shaman dress), the Ostyaks (fig. 19 – sun circle) or the Buryats (fig. 20 – representation of the moon on the left, the milky way in the middle and the sun on the right), where it crosses multiple concentric circles. The Altaians draw the stars the same way, sometimes but not always adding a halo around the motif (as previously in figs. 15, see above and 21 bottom right – representation of the sun, venus, the moon and other stars).

On Yakut drawings the crossed circle is also the symbol of a shaman drum.

shaman drum

|

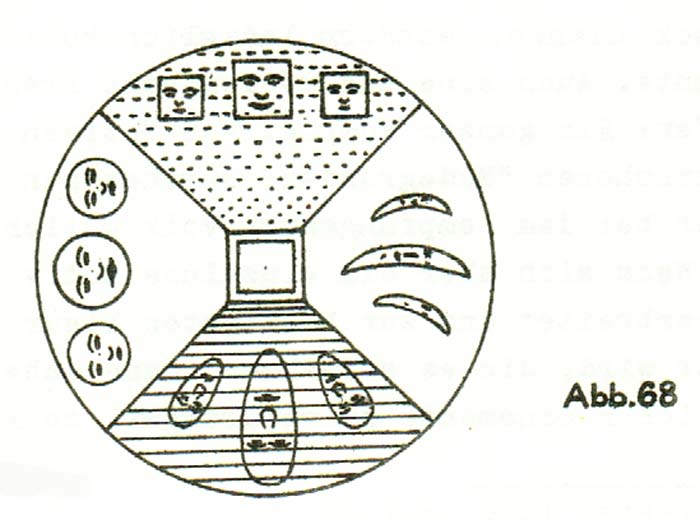

|

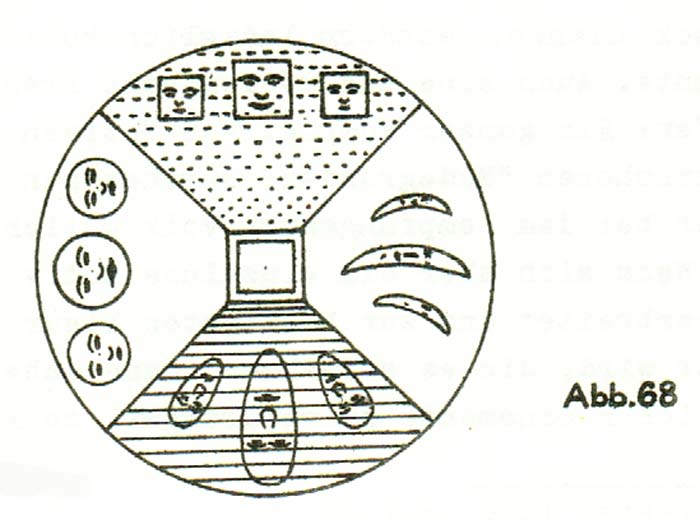

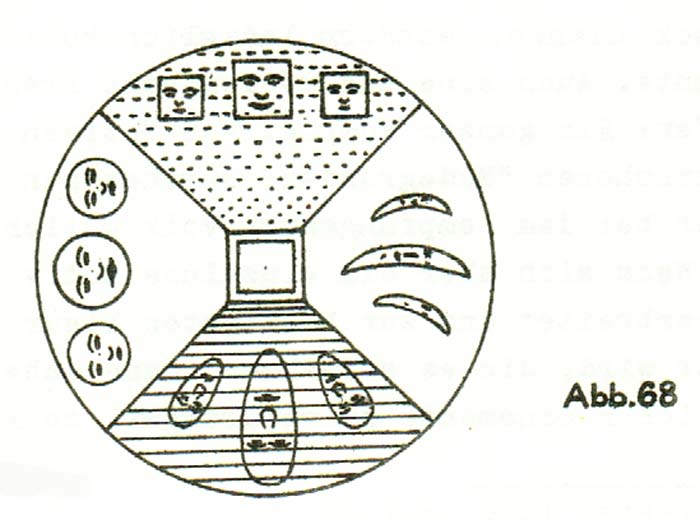

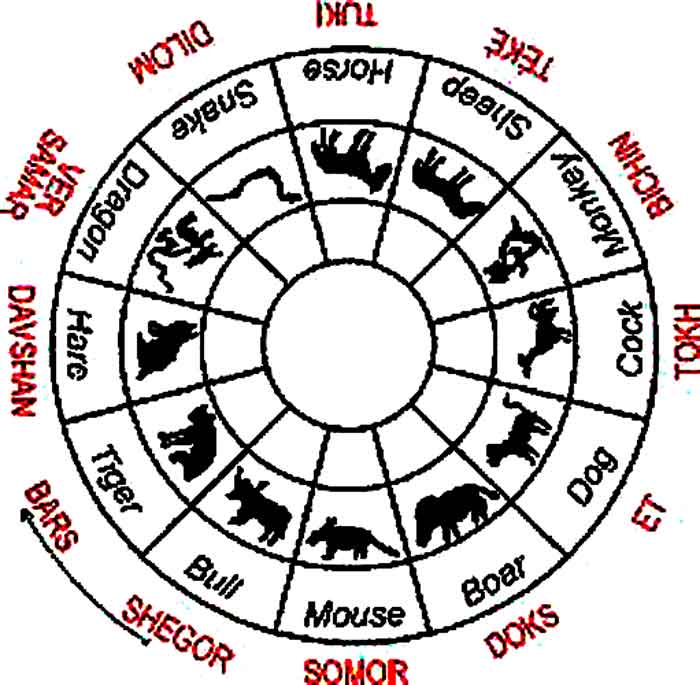

Probably this sign is used for the drum because the drumheads of round drums in North Asia and Lapland almost always have a cross drawn on them, representing the shaman’s journey. (Fig. 68 – cosmos on a drum of the Kalmyks). This cross is found throughout the drum. It shows a division into four directions and 12 different spots (the months). The Mongolian world view was influenced by Buddhism to a large extent. For them, the center of the world is the world-mountain surrounded by four continents. In summary it can be said that on drawings in the Altai the stars were often shown as crossed shapes. In North Asia the sun was sometimes also represented by circles or crosses. While the circular line can be derived from the visual idea people had of the stars, the cross goes on to express the revolution of the sun. This shape is common in all of Asia with a varying number of circles (as in fig. 21, see above). |

|

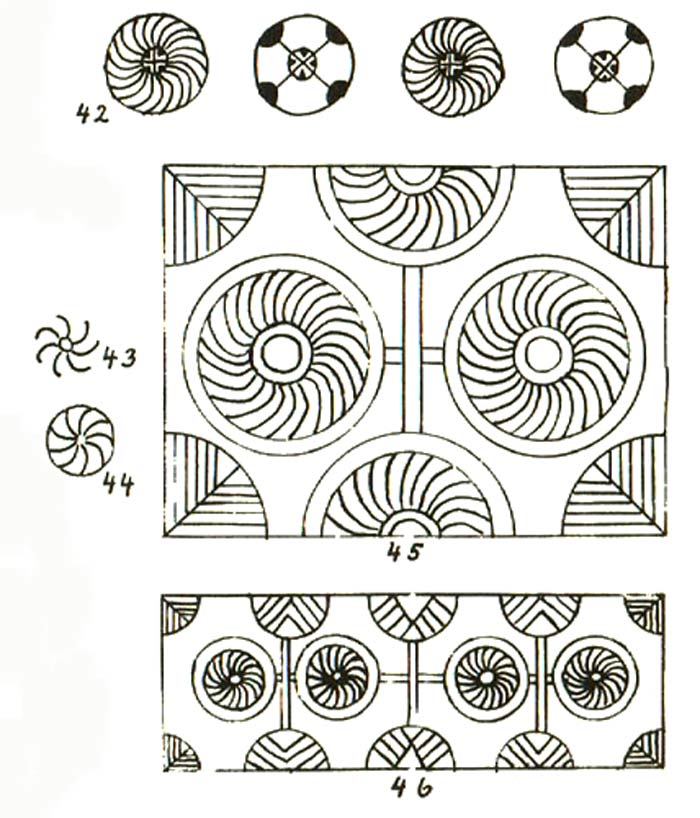

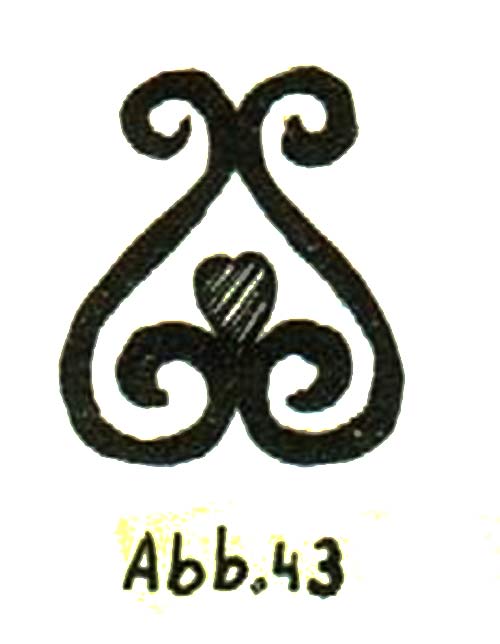

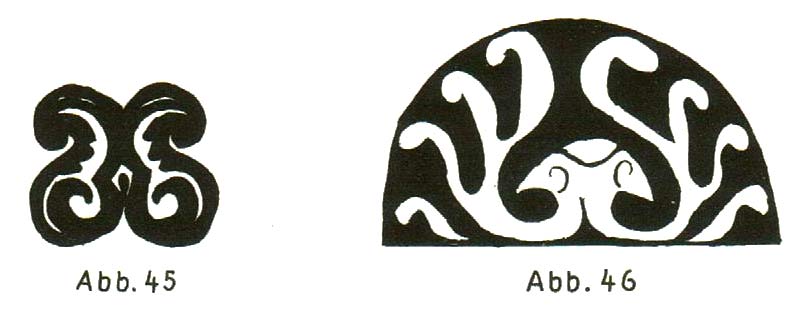

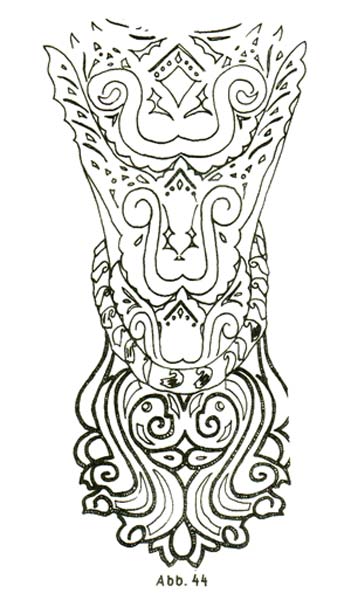

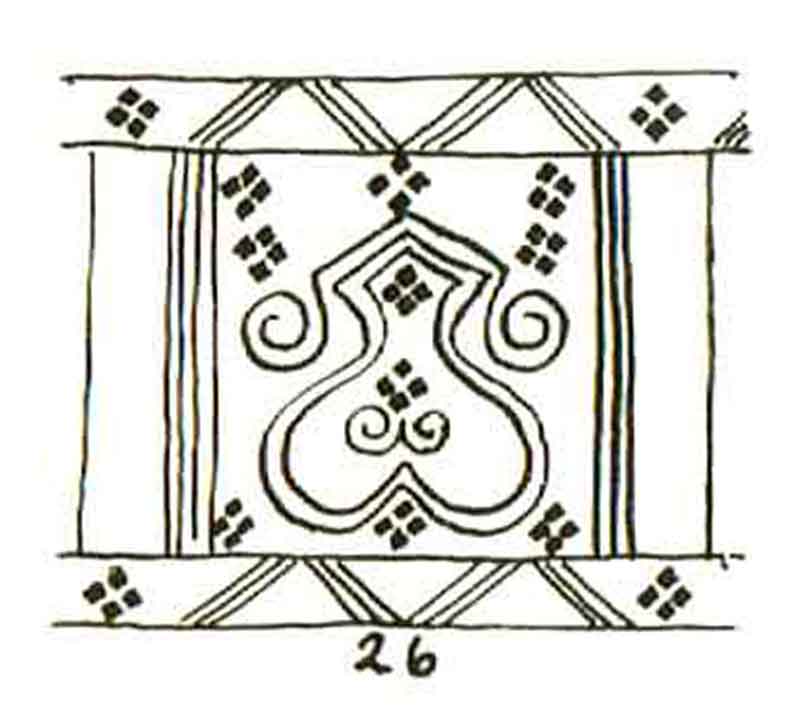

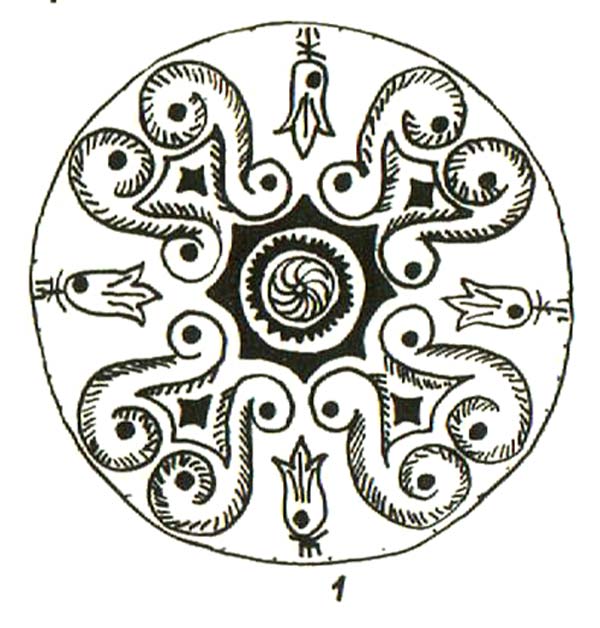

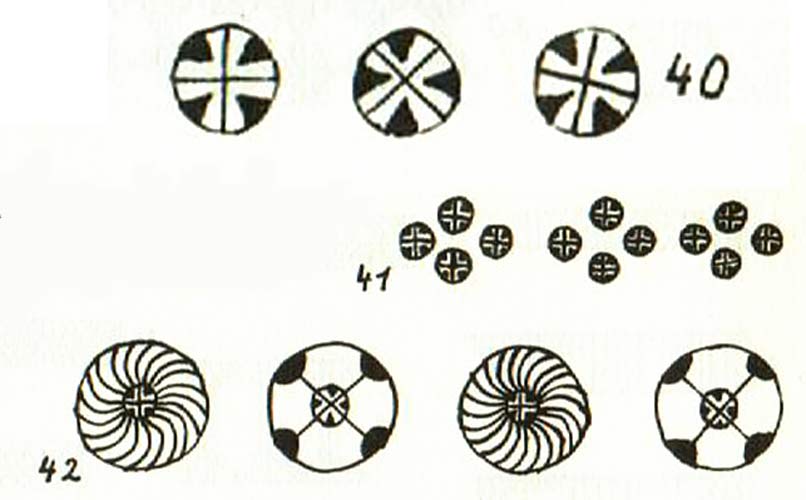

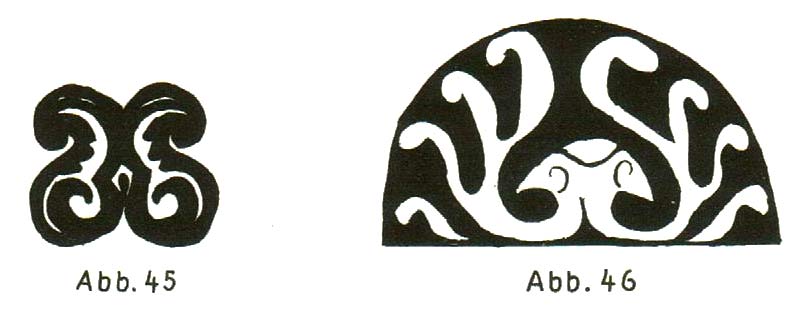

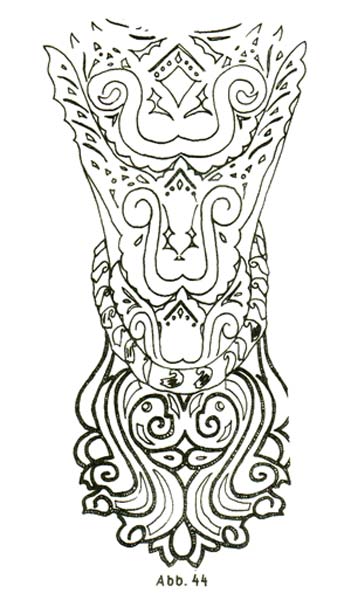

Another ornamental type of sun representation existing among the nomadic peoples of South Siberia, such as the Altaians, the Kyrgyz, the Buryats and the Yakuts, is shown in figs. 42 through 46. The beams of the sun begin to rotate, thus assuming a swastika shape. These revolving shapes are called the “sun” by the Altaians, the Kyrgyz and the Buryats. On a Yakut chest this ornament appears at the same position as on Buryat chests (panel II, fig. 45 and 46, wood, carved – 42 through 44, on a can, scored into wood). It can thus be imagined that the Yakuts and the Buryats associated the same idea with that ornament. In this context it cannot be decided for sure, whether it was adopted from Persia, where it symbolizes the sun, or maybe from China or Tibet.

|

|

|

The center of this motif usually features a circle with a spot in it in Yakut or Kyrgyz terms, which, as mentioned previously, is an ornamental expression the Buryats and some Paleosiberian peoples have for the sun.

The Buryats themselves usually draw a crossed circle in the center of this swastika symbol (a sun sign). The Altai peoples used, as a central motif, one or more spots, the cross with four spots (in this case surrounded by a circular line) or a crossed circle, which was probably used as a swastika sign as well having the ancient Indian meaning of the sun.

Cross signs or circles with a spot symbolize cosmic phenomena for the Altai peoples and the Kyrgyz, who are both related to the Yakuts, but also for the Buryats and other ethnic groups in Asia.

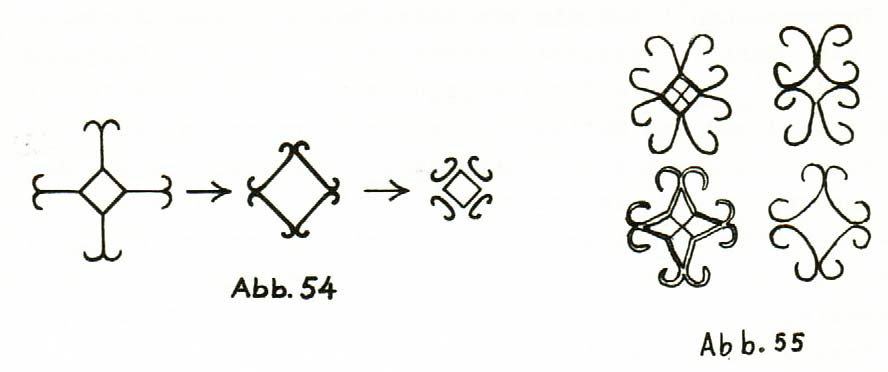

| At the center of the revolving sun symbol as a stamped ornament but also as a singular motif on silver and wood we encounter the crossed circle on which the base of the ornament is specially emphasized by four spherical triangles. This means that we see not only the pattern, which is created by a mark incised in the form of a crossed circle on pottery but also the pattern of the mark itself (panel II, figs. 40 through 42, cans, scored into wood). |

|

(40-42) sun symbols

|

This motif (fig. 40) corresponds to the Buddhist “pearl of enlightenment”. Buddhists are wearing on their foreheads or chests, like on the wall paintings in Khocho (Turfan), for example, where it already appears as a textile pattern. This motif is found in the art of non-Buddhist Asian peoples as well. As an example let there be named a magic pendand of the Ossetes (fig. 22).

This motif can be traced back to very early periods in Siberia. The ceramics of the Andronovo period (1700 to 1200 BC – Bronze Age) showed it in the Altai already. This is why it has not been determined, whether it is actually a Buddhist motif or a special form of the crossed circle. |

|

|

| Doubtless the cross made of five squares (panel II, fig. 32, decorative plate, silver, engraved) is also part of the group of the old cross motifs, as it appears in the Ostyak sun circle (see above in fig. 19). The Ugrics have been using this motif since the Bronze Age (1700 through 1200 BC). As a decorative motif it is found belonging to the Samoyedic people, the Nenets, the Kets, the Altaians, Tungusic tribes, Buryats and Kyrgyz. |

|

cross motif

|

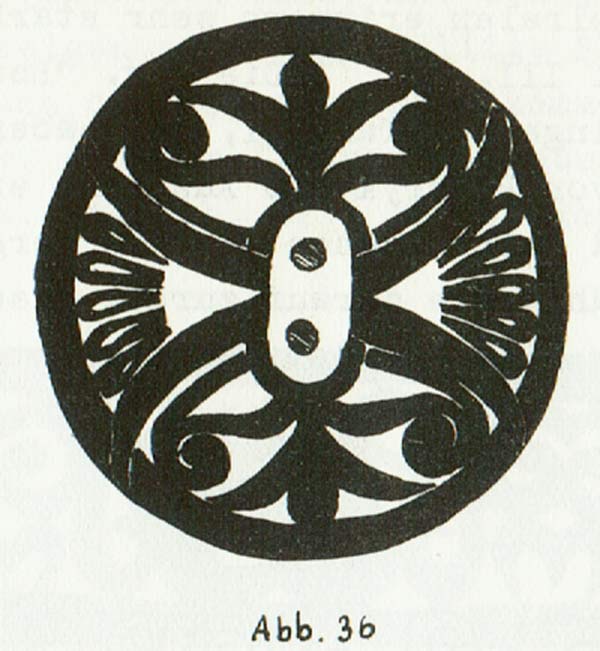

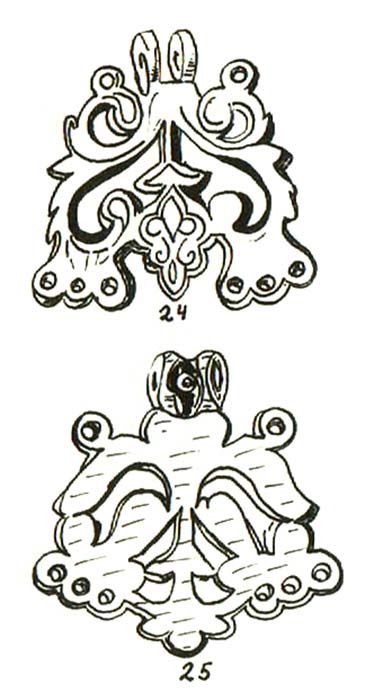

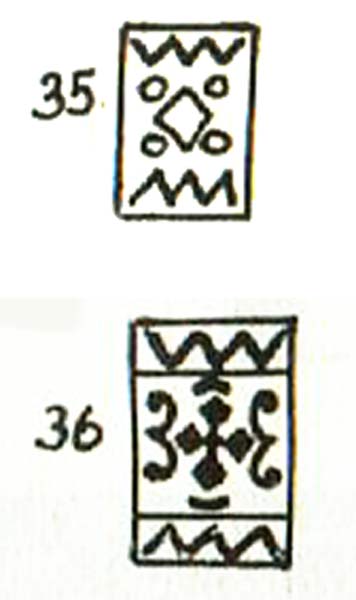

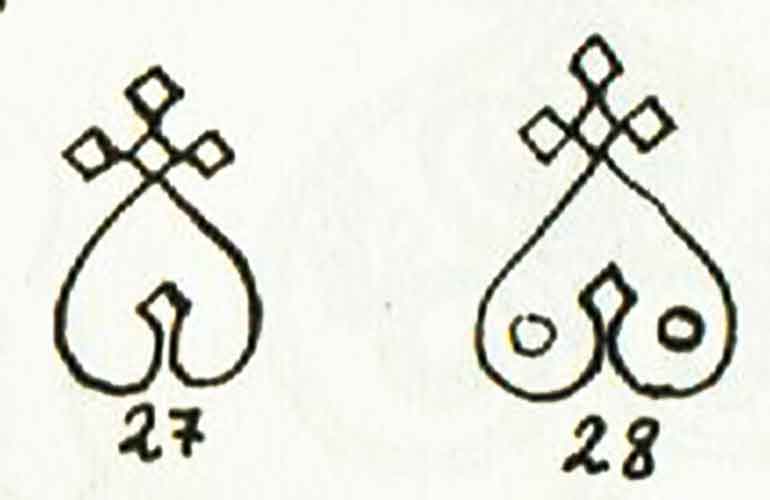

Ornaments on decorative leaflets represent ancient Siberian culture (figs. 35 and 36, decorative leaflet, silver, stamped). In a similar shape they are found in the Yenisei area and the Sarmatian territory east of the Black Sea. Here in the Altai they were used up to the 5th through 8th centuries AD.

|

|

decorative leaflets

|

| Among contemporary Siberian peoples the Ostyaks are the last ones to produce patterns like this the same way the Yakuts did (panel II, fig. 26, potter mark, wood, carved). |

|

four crosses

|

| In the Ordos area the stitched decorative plates looked different during the period of the Han dynasty. Their pattern was a fox’s head with two rosettas. The decorative plate (panel II, fig. 38, silver, stamped), in which the smith stamped two nooks and a spot, resemble this kind of stylization. |

|

fox's head

|

A very common serial ornament consists of the base of a cross pattern in the form of four squares and alternately a crossed circle with a size nine times as large (panel II, fig. 49, can, scored into wood).

|

|

squares

|

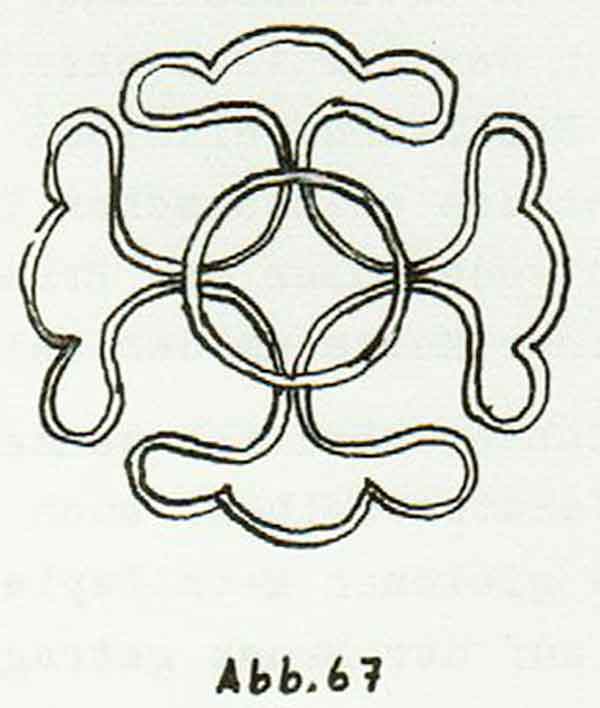

Another variant is “timäx tördö oju”, the button base ornament (panel II, figs. 47 and 48, kumys container, scored into wood). The motif, consisting of inscribed rhombi, has been stitched as a base onto the coats in order to avoid the buttons being torn off too easily.

The singular square standing on its tip, sometimes contorted to form a rhomb, seems to be used as a sign of hallowness or blessing on ancient Chinese bronzes of the Chow culture between the beaks of animal heads. It is often replaced by two inscribed rhombi. This is just the same shape the inhabitants of Celebes (now known as the Indonesian island of Sulawesi) still use today to decorate their carved buffalo heads. The rhomb motif is not only present in Eastern Asia but also in the Middle East and in Southern Siberia.

|

|

(47+48) avoid the buttons

|

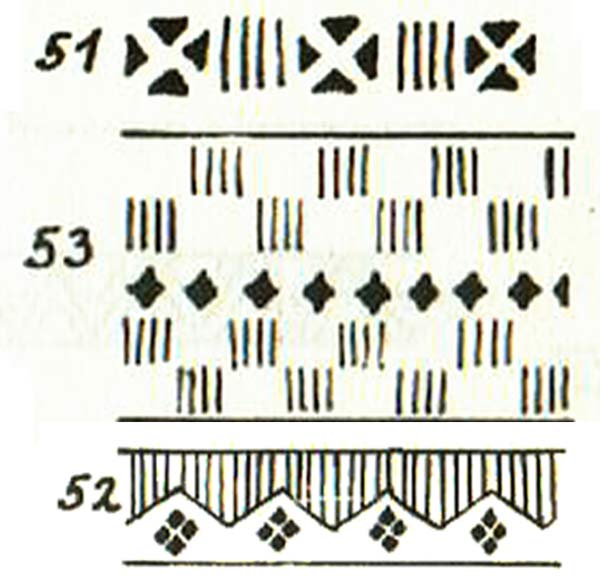

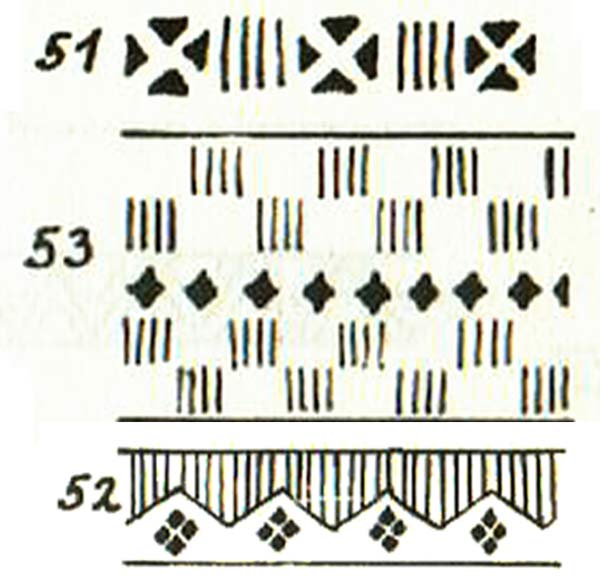

The crest pattern is also often associated with various cross ornaments (panel II, fig. 51, saddlecloth, cloth mosaic). For example, on a wooden container (panel II, fig. 53, tin, scored into wood), plain squares were connected by the crest pattern (panel II, fig. 52, cup, wood, carved), and a zigzag pattern was added as a third element..

|

|

cross-crest pattern

|

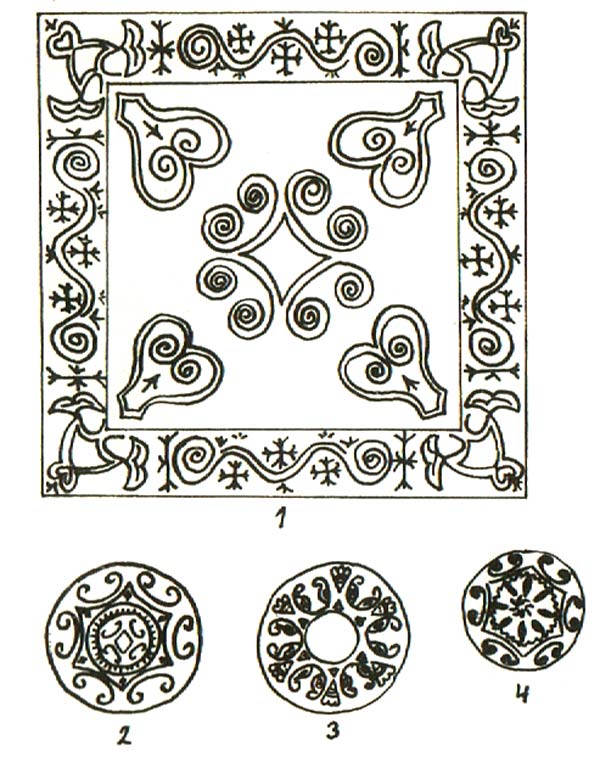

|

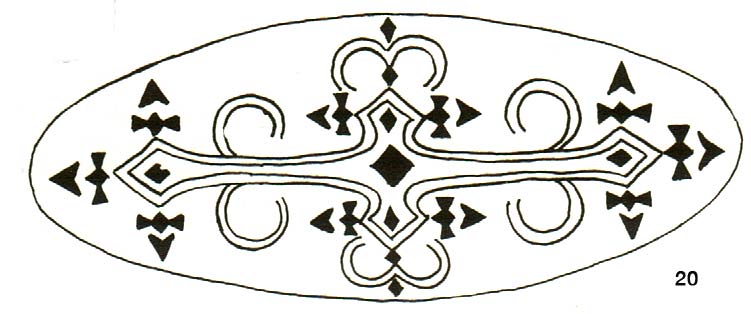

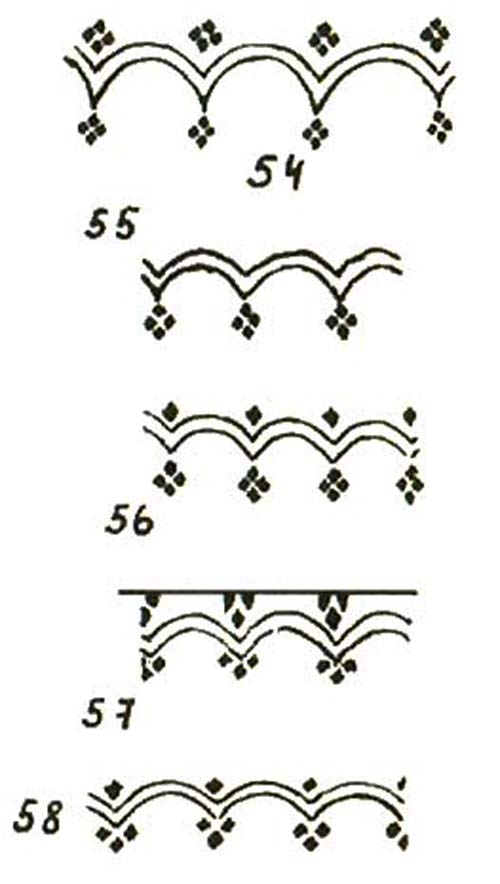

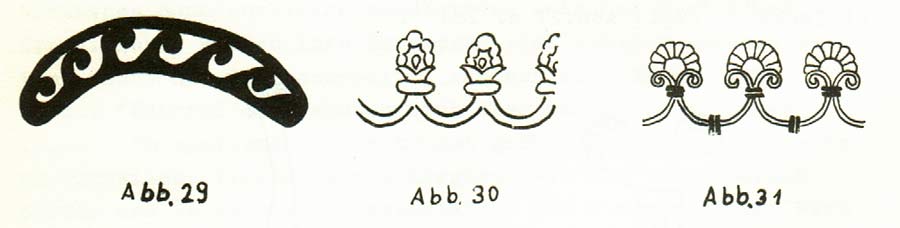

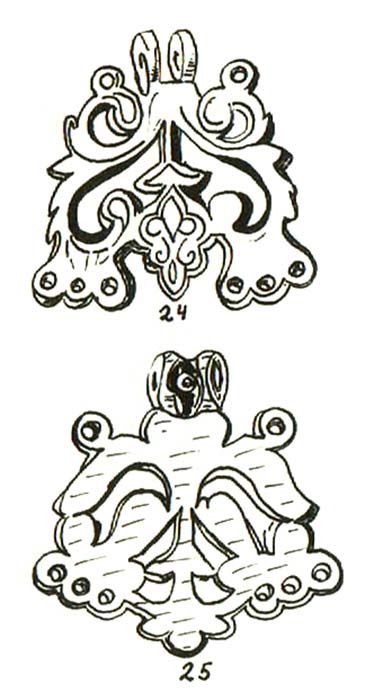

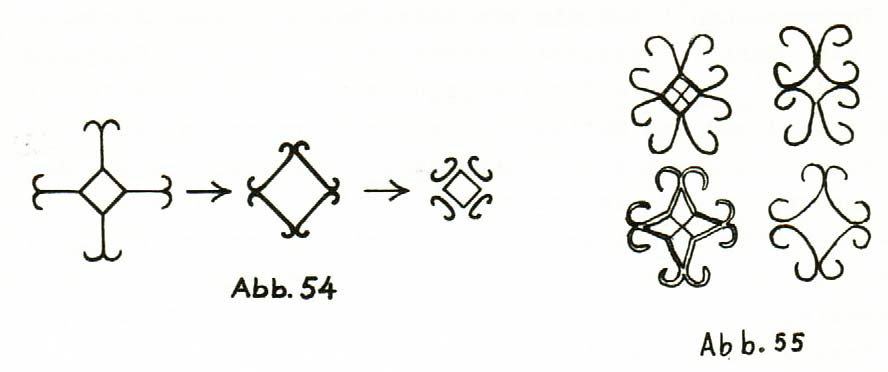

The sky ornament:

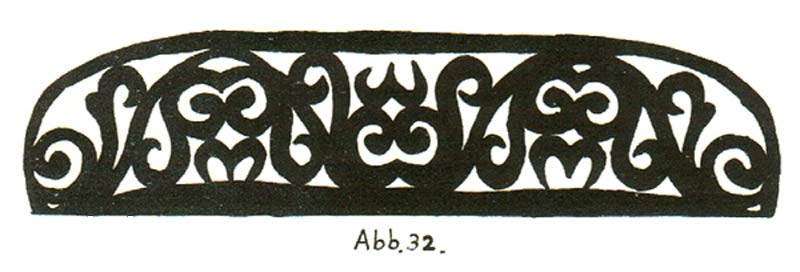

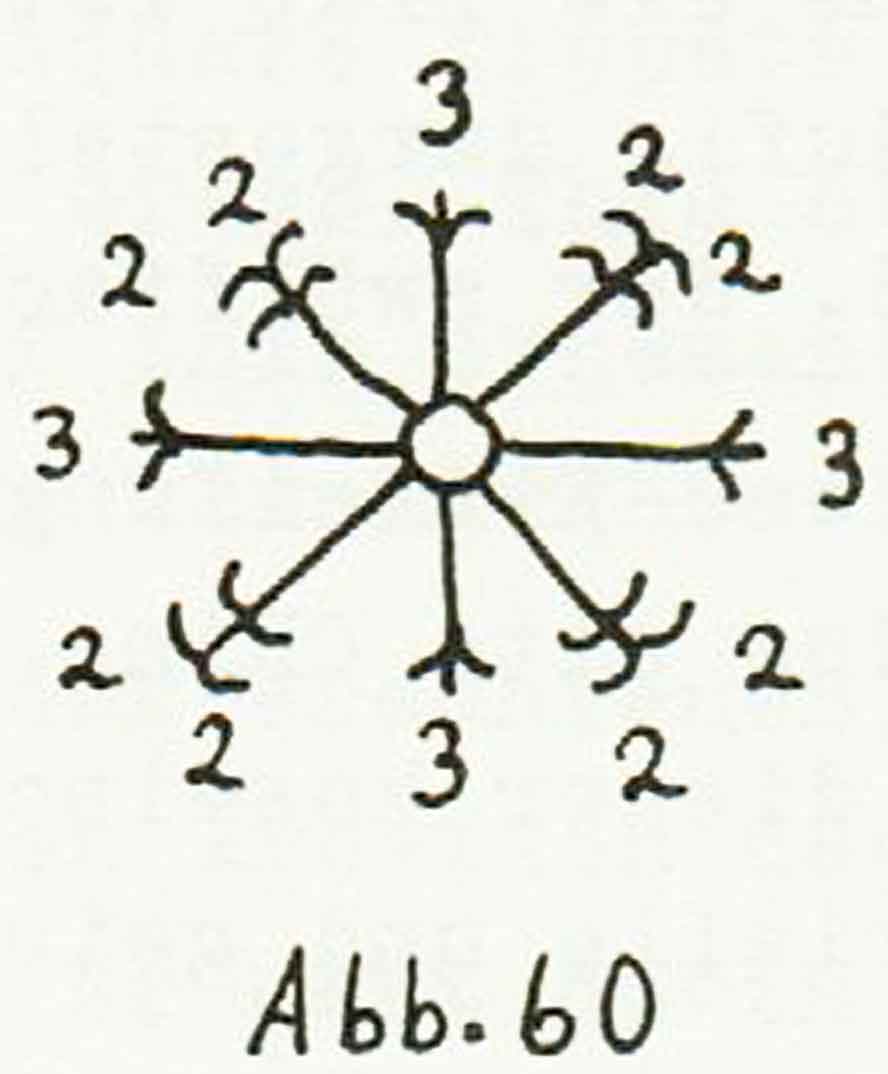

One of the most common ornaments in wood is the linking part of double arches connecting and potentially touching each other. It is called “sarbynnax oju”, “suspended ornament”. The pattern is always the same, consisting of an arch and a cross figure (panel II, fig. 54, box, scored into wood, and 55 through 58, kumys container, scored into wood).

This sky ornaments occurs as an imitation of the round dome. The shapes derived from the cross, which, as mentioned above, represent stars, confirm that these shapes probably had an astronomic meaning.

|

|

sky ornaments

|

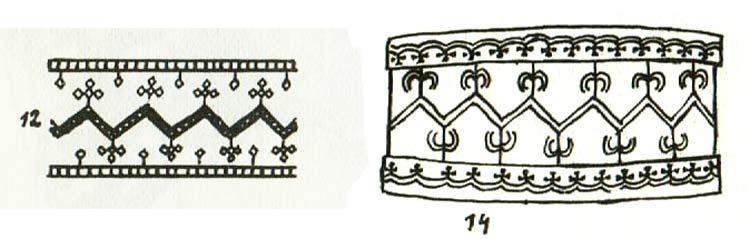

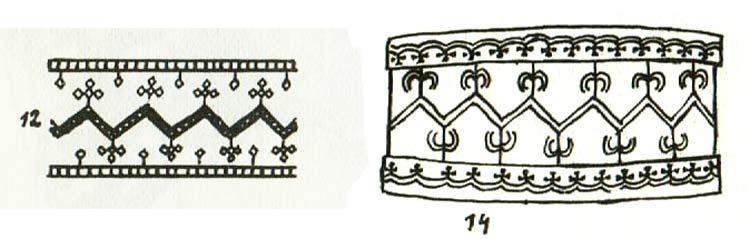

In a few cases not only the base but the pattern itself, the cross, connects to the arch line (panel III, fig. 12, wall hnging, bark piece, stitched, and 14, tin, scored into wood).

|

|

(12+14) wall hanging and tin

|

Another work on silver has two circles scored into the round shapes (panel III, fig. 1, braid ornament, engraved).

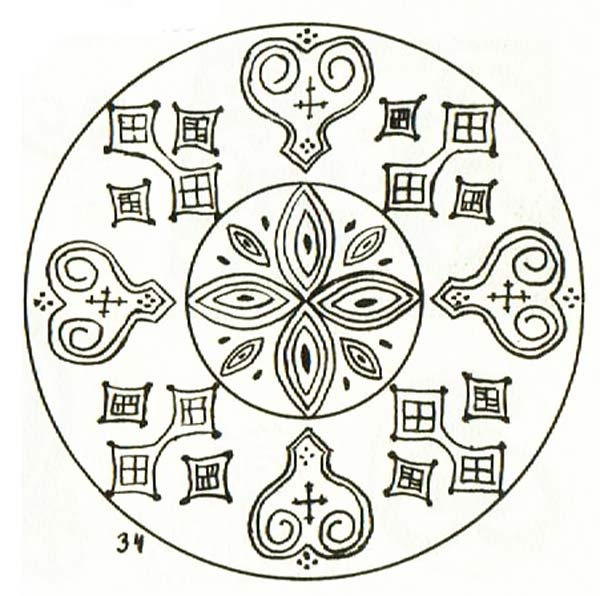

In many cases the group of four squares is replaced by a single square, which is placed on the top side directly within the gussets of the arches but seems to be suspended on a rope or hanging on a string on the bottom side (panel III, figs. 2, 5, kumys container, scored into wood, and 3, kumys container, wood, chip carving).

|

|

|

When an outline is drawn around this ornament, this creates one of the characteristic ornaments of the Tungusic people (fig. 23).

|

|

|

| The Yakuts themselves liked to decorate many objects of their personal belongings or clothes with this ornament (panel III, fig. 6, kumys container, wood, chip carving, and 7, coat with silver plates stitched on it). |

|

sky ornament

|

Judging from the material at hand, which was probably collected earlier, the ornament is in some way associated with the Tungusic people. We have reason to believe that this ornament was common among the Tungusic and Yakut peoples, or, more specifically, among their ancestors, who lived in the Lena area around the Nativity. The Yakuts changed the ornament multiple times; no other Northern Siberian people was more enthusiastic about variation than they were.

The variant from which it is easiest to discern the basic shape, is a plain arch element with a single square (panel III, figs. 3 and 4, kumys container, wood, chip carving).

|

|

sky ornament

|

|

Things are somewhat more complicated when it comes to the pattern (panel III, fig. 8, kumys container, wood, chip carving, and 9, cup, wood, chip carving).

|

|

sky ornament

|

A form of the sky ornament that was common among the Tungusic people has been duplicated here, as shown in figure 24.

Apart from the Tungusics, there is only one more parallel to the Yakut sky ornaments (panel III, fig. 12, wall hanging, bark piece, stitched). It was found on an urn from the Sille period in North Korea (57 BC to 935 AD), which is approximately the same area that is also regarded the original home of the Tungusic people.

|

|

wall hanging

|

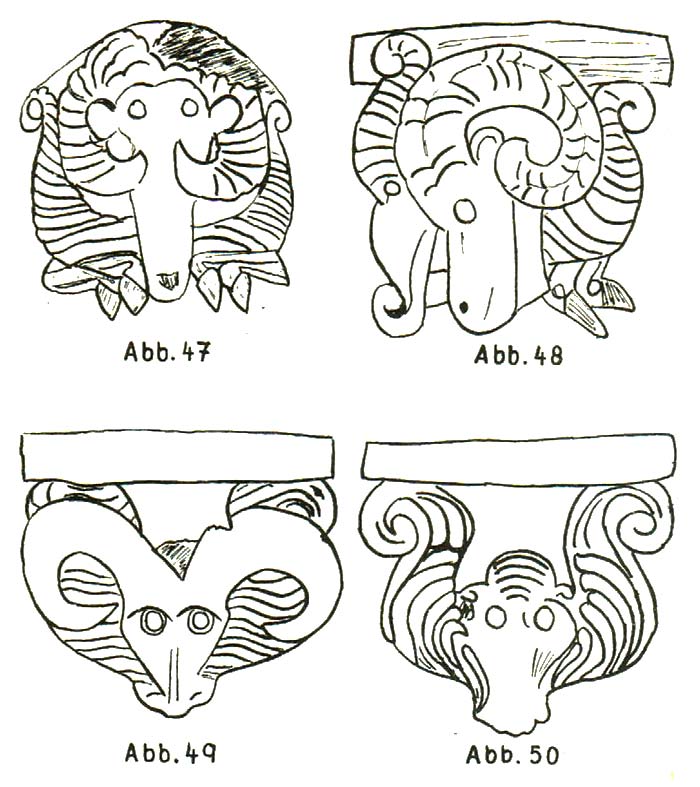

The Yakuts received many inspirations from China, especially from the north. Among these are rams’ beaks, which are proven to be mediated by the Tungusics. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to find out the exact place of origin or acquisition. However, motifs similar to the Yakut sky ornament are very common in Asia.

In fact, jag patterns are a popular lace among the Buryats. They are applied on the inside of a yurt where the vertical rods reach those of the roof. The Yakuts always use the zigzag or the arch with crosses, i.e. some kind of sky pattern (panel III, fig. 5, kumys container, scored into wood, and 12), on old wall hangings from birch bark, which used to be suspended inside tents of that time.

borte

|

|

Small round silver disks (left side), each having a rosetta with eight leaves in their center attached to short bead strings in the center of each arch, representing the sun, demonstrate how vividly the Yakuts imagined the sky.

The patterns described above can be summarized as one group. Their basic shape is the cross. The Yakuts are by far not the only people who use these ornaments. The Ostyaks at the Yugan use exactly the same stamp made of reindeer horn to press patterns onto the soft birch bark or onto tins.

|

Squares with an inscribed cross represent stars. Crossed circles on the other hand are often considered to be representations of the shaman drum. As we know, the crossed circle is a symbol of the sun almost everywhere, and has been for a long time, just like the crest and the triangle ornaments. It was already there in times when the use of metals was not yet known to these ethnic groups. Many peoples of today still depict the sun and the stars the same way. Crosses are still found with a double arch line, these are “sky ornaments” with the crosses representing the stars in the sky.

The ornament made up by a group of four triangles is even more common. Among the Finno-Ugric peoples it is the Komi people and the Udmurts, and in the European part the Russians who call this motif their own. In Siberia it belongs to the jewelry of the Samoyedic, the Yurak, the Ket, the Yenisei-based Tungusic, the Dolgan, the Tuvan, the Shor, the Altaian, the Kyrgyz, the Karakyrgyz (Mountain Kasakh) and the Mountain Tadjik peoples, and it is found even with the Mongolian Buryats). .

|

The Geometric Surface Ornaments

|

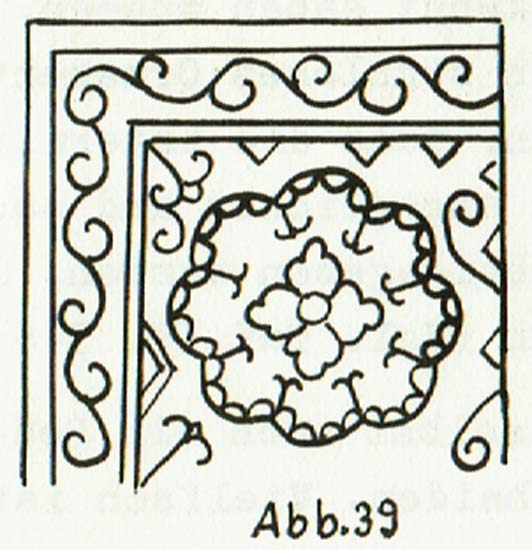

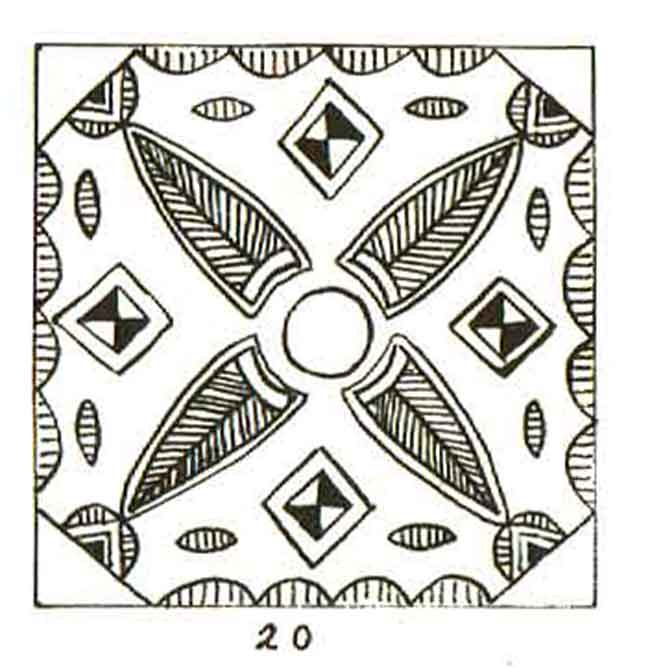

As for their set of motifs, the geometric surface ornaments are no different from the serial ornaments. Also the borderline between surface and serial composition cannot be determined for sure because a surface very often is covered with serial ornaments (panel III, fig. 17, carpet, fur mosaic). The geometric surface ornaments, however, are fairly rare. Only a single ornament (panel III, fig. 13, saddlecloth, textile mosaic) has a surface character, being cut off entirely by the delimitation of the surface and not having an organic ending. Works like this were found at the Yenisei, originating in the 3rd century BC, and in the Altai area, dated to the 2nd century AD.

Their outlines are accompanied by a variant of the sky ornament (panel III, fig. 5, as on kumys containers, scored into wood). The execution of the squares seems to be not particularly thorough. The shape of the following ornament (panel III, fig. 7, like on coats, having silver plates stitched on) is located on the left short side. The sky ornament is emphasized by two of the figures cut out in rhomb-like shapes bearing four spots, which are derived from cross motifs.

The ornaments on one chest (fig. 15) are completely out of the ordinary.

This decoration seems alien among the remaining Yakut patterns. Maybe it is a calendrical representation, as its central part shows 15 squares (15 being half the number of days of one month), supplemented by the circular “head” and the largest of the squares. The number 15 is very important for the Yakut calendar because the Yakuts break their months into a dark and a light half. The second half, which is considered dark or “old”, was numbered backwards (i.e. the 15th, 14th, 13th day, etc.). In this but also in other details, the Yakut calculation of times bears resemblance to that of the Indians, the Persians and the Tibetans. The seven carved figures on the left short side represent the weekdays.

With the exception of a few metal works, the material for geometric ornaments is always wood, clay, cloth or fur. Smiths had their own patterns. It is virtually impossible to identify the exact origin of these plain geometric motifs. Triangles, zigzags, arches, squares, etc. occur among all neighbouring groups, and they belong to the ornamental art of various peoples.

Many of these motifs appear in finds of very early periods of Siberian history (2000 until 3000 BC).

|

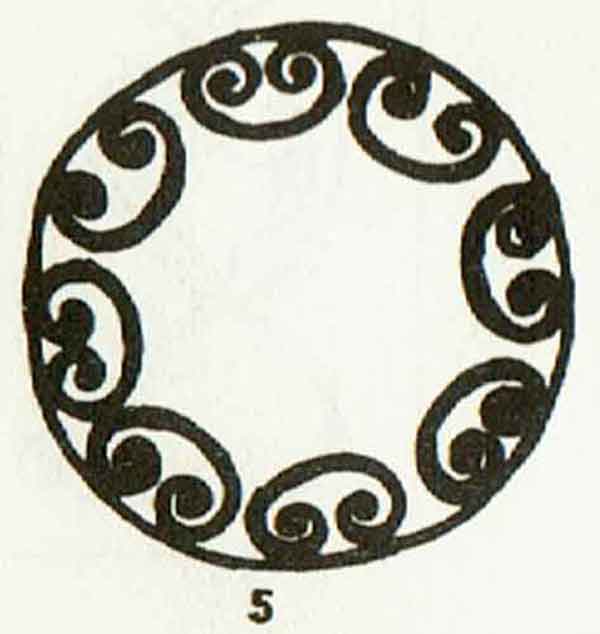

The Spiral and Plant Ornaments

This type of decoration is found less frequently in connection with Paleosiberian, Tungusic, Samoyedic or Ugric tribes.

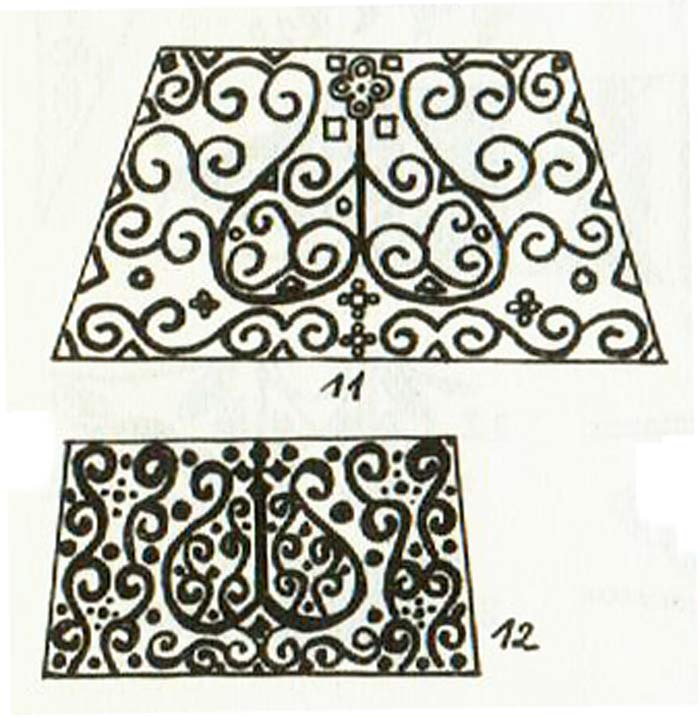

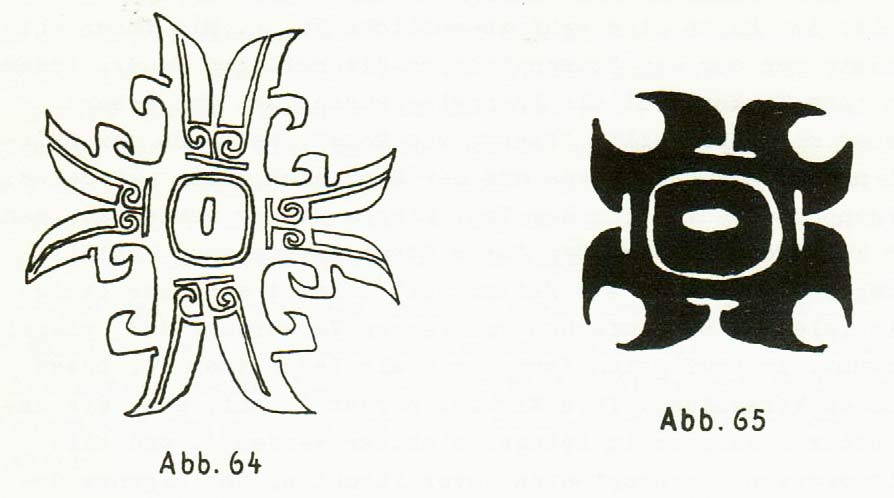

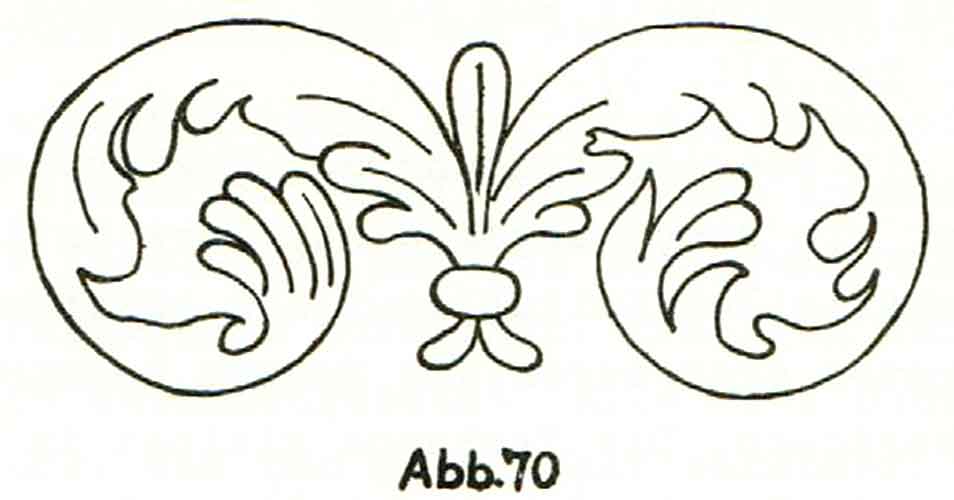

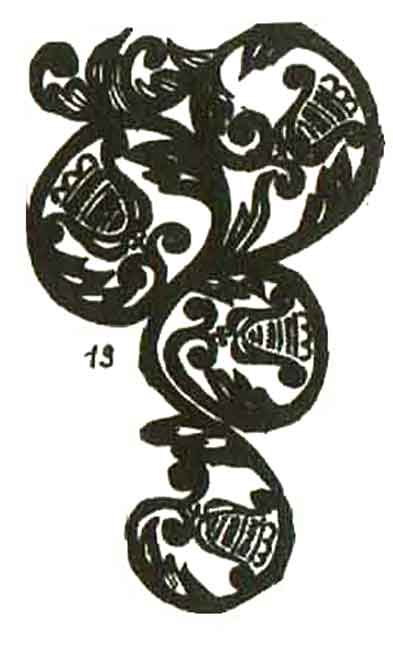

Among the Paleosiberian tribes the Amur peoples, i.e. the Gilyaks and the Ainu, and among the Tungusic tribes the Golds, the Orok and the Oroch people constitute an exception in using the spiral to a great extent. These patterns, however, are clearly different from the Yakut ones, in that they are never intertwined but each part is fully visible, though of course, two spirals may touch. In these drawings (the plant ornaments) it is easy to identify Mongolian, Russian, or even Chinese influence, and also a relation to the Kyrgyz or other Turkic peoples of Southern Siberia. In particular, many Russian tendril and baroque ornaments were adopted. The Yakuts were the masters of spreading imitations. In contrast, the Amur peoples presented their spiral ornaments as woven ribbons, in which individual ribbons are intertwined. These motifs, again, are entirely different from those of the Yakuts. Various transformations of the animal head, the so called Taotie (fig. 109, bottom) of a fish or a bird do not exist as such on Yakut objects. So, no closer relation is to be discovered between the two areas where spiral ornaments used to appear.

Taotie

|

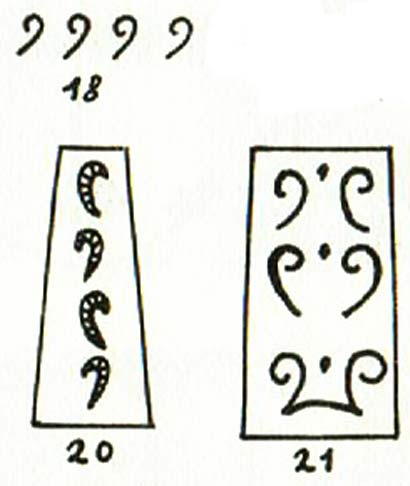

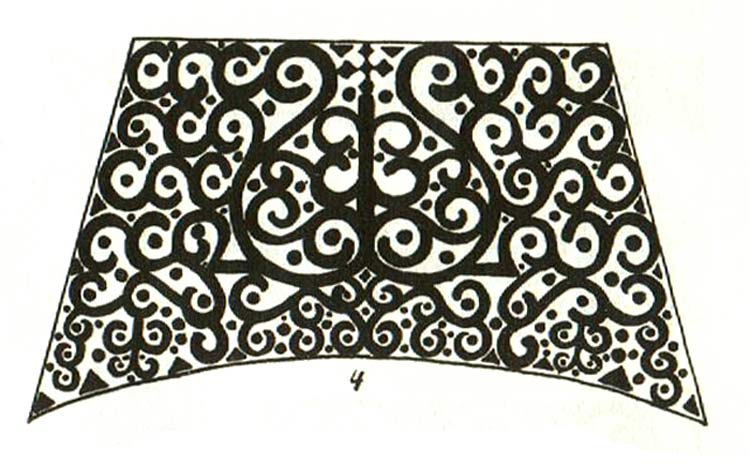

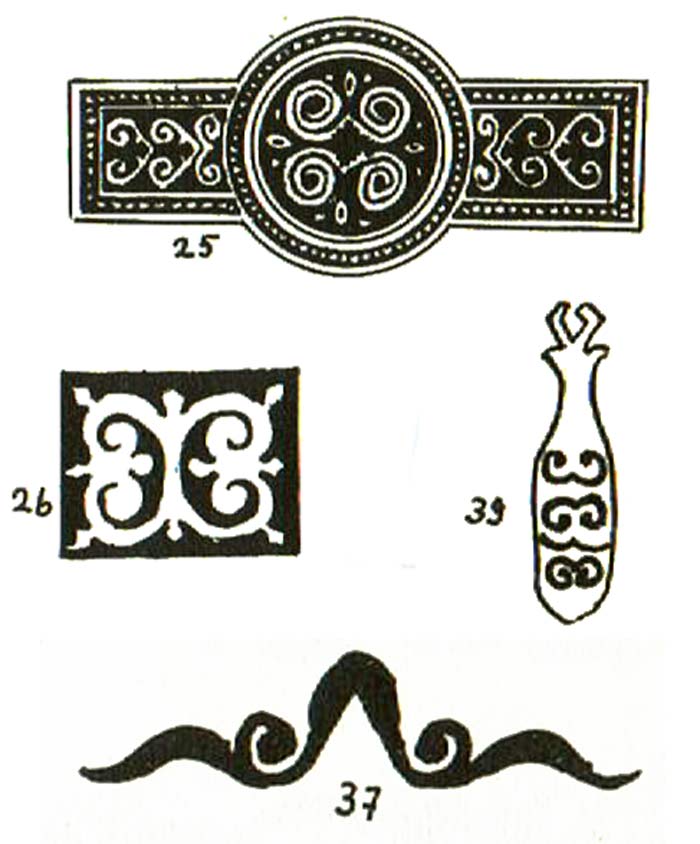

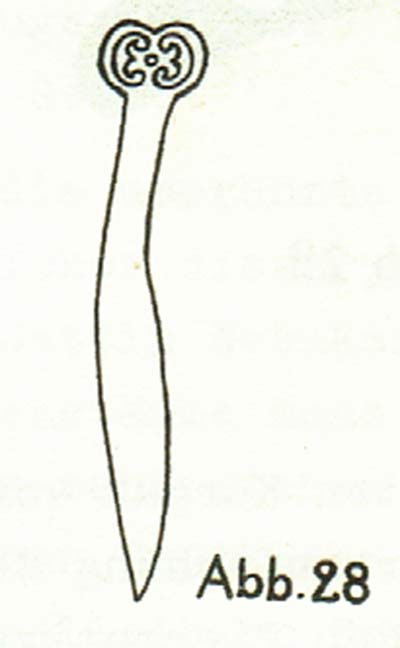

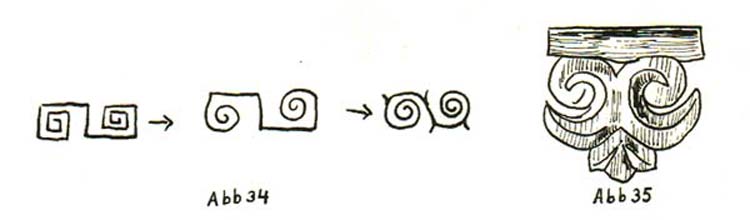

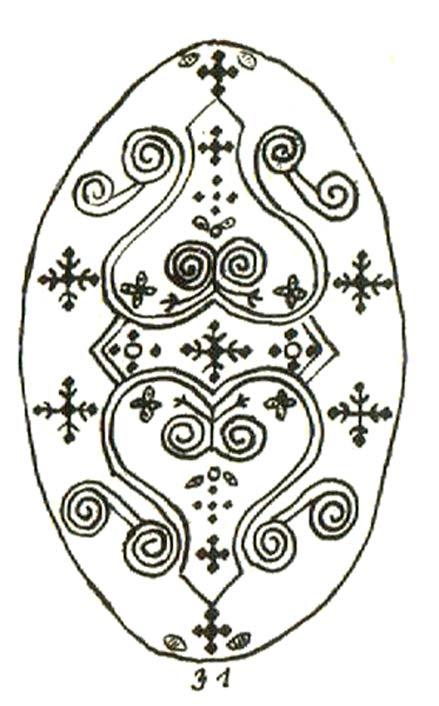

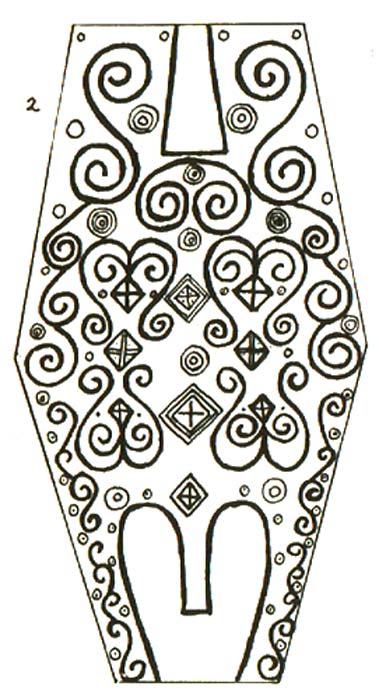

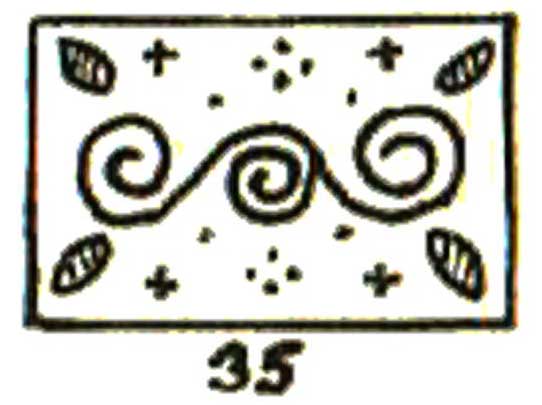

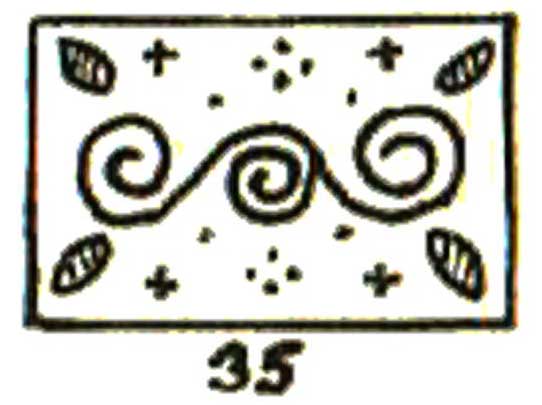

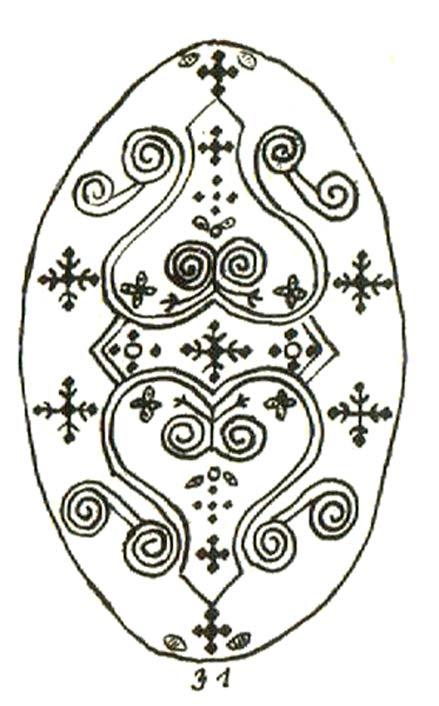

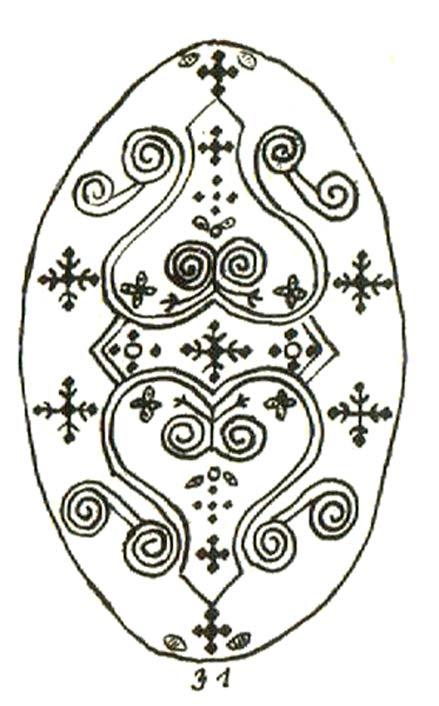

The spiral: The simple unbonded spiral is very rare among the Yakuts. On one pair of tweezers and one decorative disk (panel III, fig. 18, silver, engraved; 20 and 21, tweezers, silver, engraved) the spirals are arranged in a horizontal or vertical line, each completely detached from the other, while on a different decorative disk (panel III, fig. 24, shoe on male belt, silver), the spirals touch to form a serial ornament.

The spiral is a popular motif on saddlecloths. Each spiral has a different color (panel VI, figs. 4, 8 and 10, cloth, embroidery, 6 and 13, cloth, stitched, and 14, leather, stitched)..

|

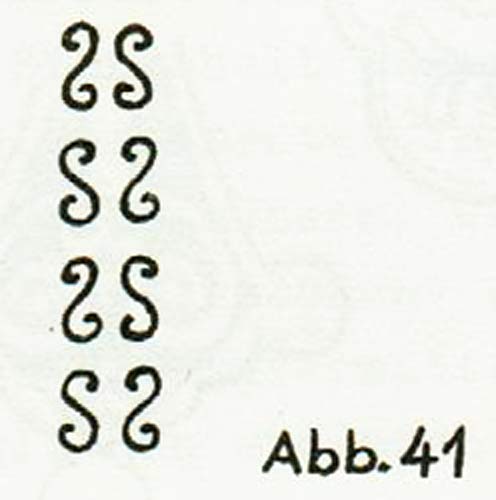

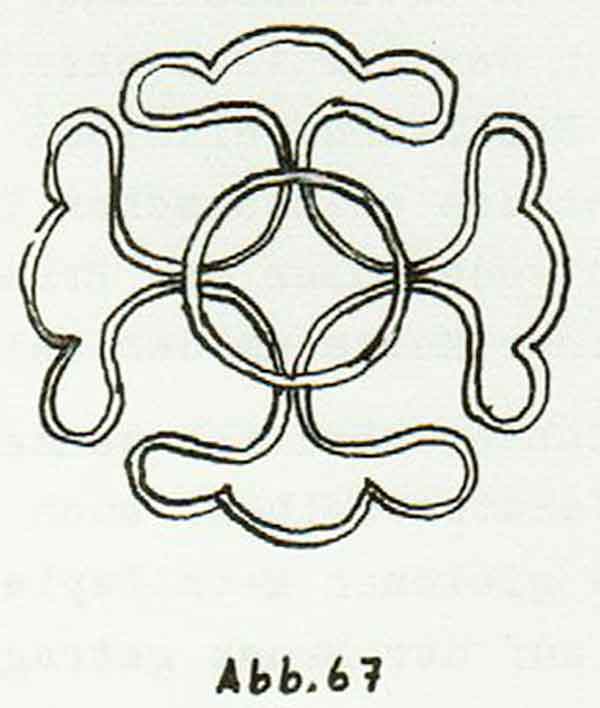

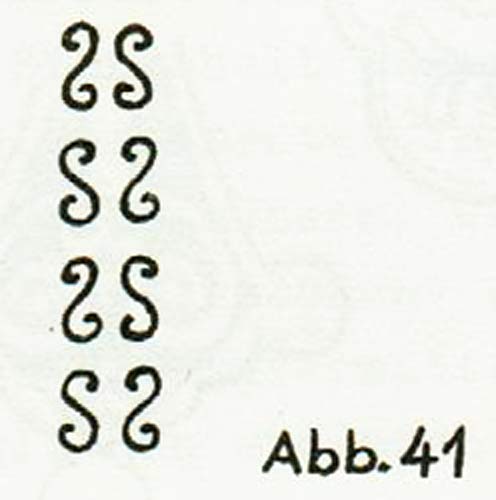

A double curl on both ends of a line is much more common than these plain spirals (panel III, figs. 25, 37, on a belt buckle, silver, semi-relief, and 39, probably depiction of a cow, carved). They extend either in two different directions, forming the so called S-shaped spiral, or both in the same direction (panel III, fig. 26, shoe on harness, silver, engraved). |

|

spirals

|

| In most cases, the S-shaped spirals are located not individually between the other motifs but combined to form rows together (panel III, fig. 28, lancet, iron, engraved, 29 through 31, decorative plate, silver, engraved, 32, box, scored, and 33). |

|

|

The members of a silver chain are sometimes forged the same way (panel III, fig. 38, glove, leather, stitched, panel X, 23 and 24, box, scored into wood).

This motif is found on both wood and metal works.

|

|

spirals

spirals

|

|

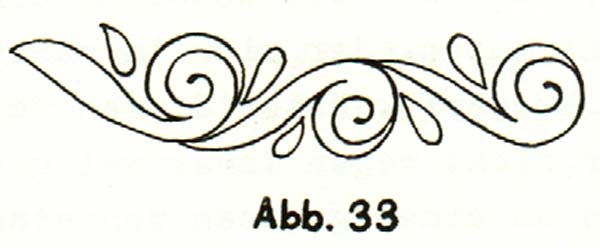

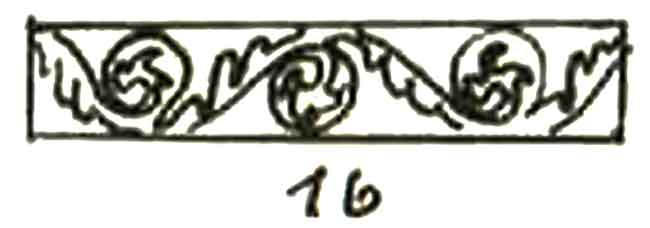

The tendrils:

A good example of tendril and spiral is this pattern on a wooden box (panel III, fig. 35, box, scored into wood).

tendril

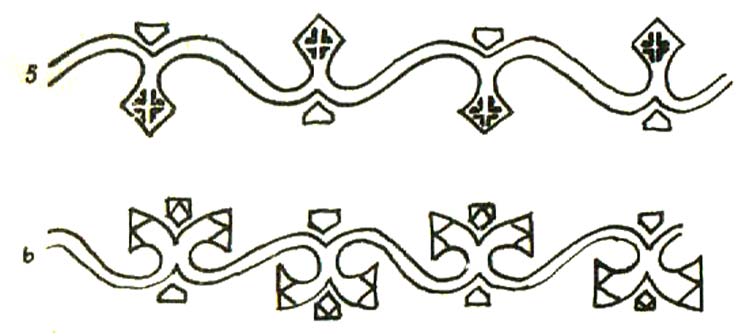

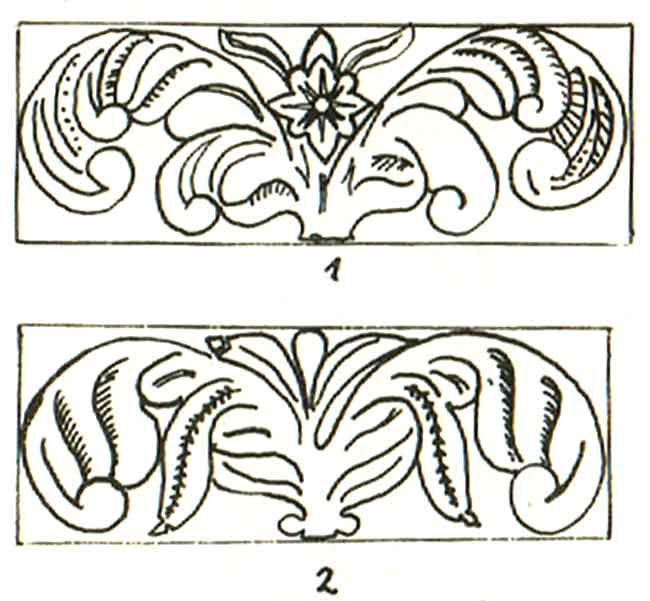

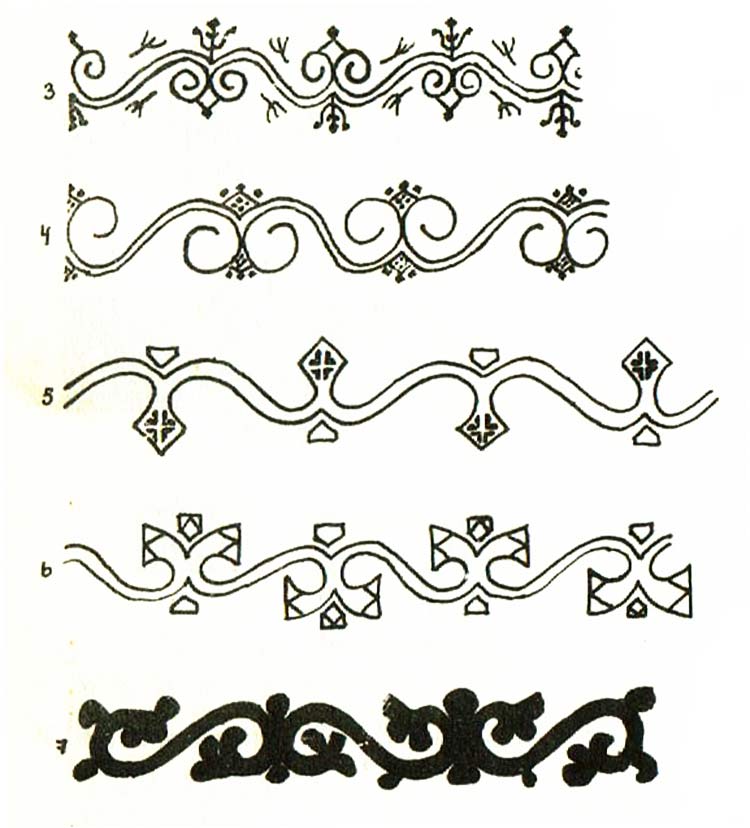

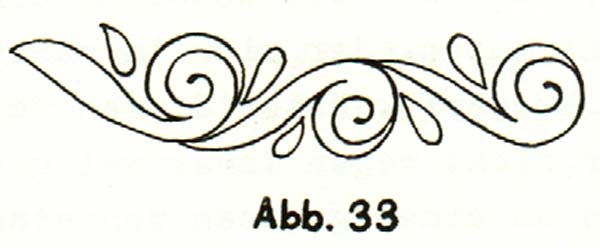

The intermittent curling tendril (figs. 3 through 7) is composed of S-shaped spirals.

In the art of Greece and the Middle East, the term “curling tendril” has been established in various languages. One differentiates between a simple and an “intermittent” curling tendril, which is also relevant for the Yakut ornaments (panel IV, figs. 3 through 6, box, scored into wood, and 7, decorative plate, silver, engraved). |

|

(3-7) intermittent curling tendril

|

On the other hand, the simple curling tendril is more similar to a natural stem of a plant (panel IV, fig. 10, box, scored into wood). The stem of the curling tendril was drawn with a double line.

|

|

simple curling tendril

|

The Yakuts always designed their intermittent curling tendrils with two lines. However, if the ends of the spiral curl very extensively, they ceased to continue the double line. They viewed these tendril ornaments mostly as plant patterns, so they rarely designed them in a different manner.

One wooden chest bears a very unusual version of the plain curling tendril (panel IV, fig. 13, kumys container, wood, chip carving).

|

|

curling tendril

|

On one wooden can, the intermittent curling tendril has four spots, with squares serving as fillers (panel IV, fig. 4, scored in wood).

|

|

|

In this image we see very clearly that the motif has been incorporated into the pattern (panel IV, fig. 5, box, scored into wood). The spirals are absent altogether.

Another variant of the pattern has the fillers of the sky ornaments evened out (panel IV, fig. 6, box, scored into wood).

|

|

|

| (Panel IV, fig. 24, bracelet, silver, engraved): an example of the third form of the Yakut tendril. It is based on the double spiral, in which both curls are facing in the same direction, and are connected by plant motifs. |

|

|

| Parts of the pattern can be viewed in more detail in the ornament on this bracelet (panel IV, fig. 25, silver, engraved). |

|

|

|

The individual double spirals do not coalesce directly. This form of tendril is used for more complex plant ornaments on smithery work, whereas it is never found on domestic products.

There is one pattern where the tendril ornament is comprised of double spirals facing only in one direction (panel IV, fig. 11, on calendar, silver, engraved)..

|

double spiral

|

The rounding of every double spiral is cut through twice (panel IV, fig. 12, saddle, silver, engraved).

|

double spiral

|

Plant motifs: The Yakuts did not include a single plant from their indigenous flora into their traditional set of motifs, altough more than half of the objects they processed are decorated with various plant ornaments. Authentic imitation was not common in their art. The primitive people were mostly satisfied with depicting those objects by geometric shapes that strongly influenced their way of thinking, i.e. mainly dangerous things like demons, spirits or human beings who had specific powers. This raises the question of how much religious content these ornaments contained. A plant will not appear in a simple person’s mindset unless it symbolizes some kind of power or is used for cultic purposes. This might explain why some plant motifs are virtually absent from the Yakut culture. The plant motifs often include the basic shapes of spirals or tendrils. They are not indigenous motifs but assumed from the high cultures of Asia.

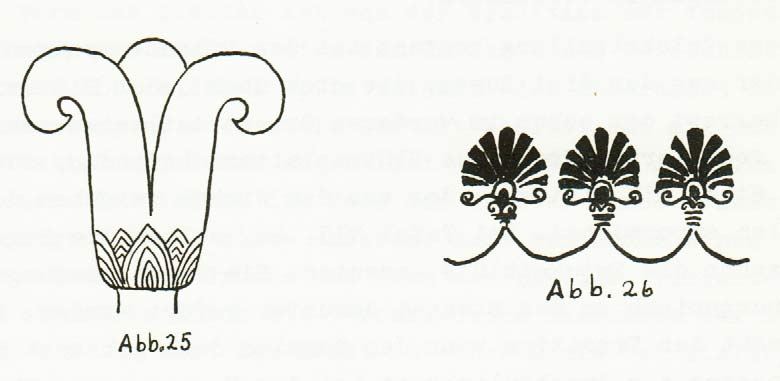

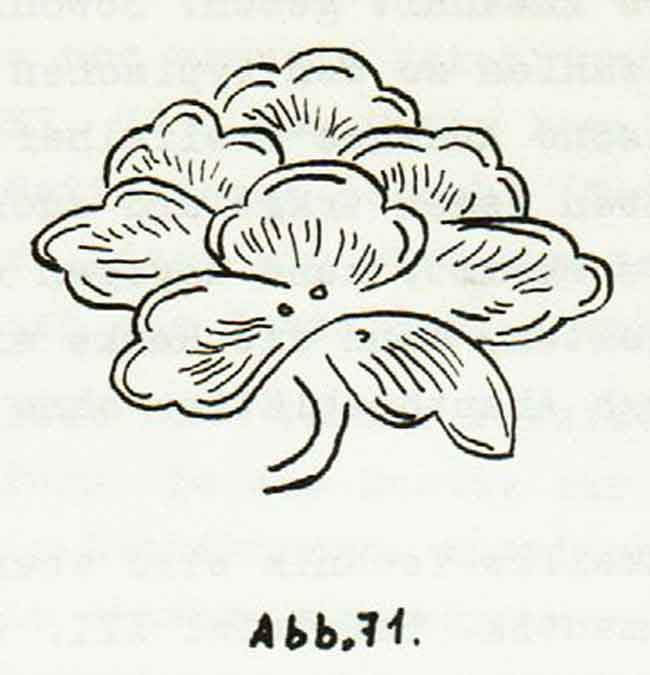

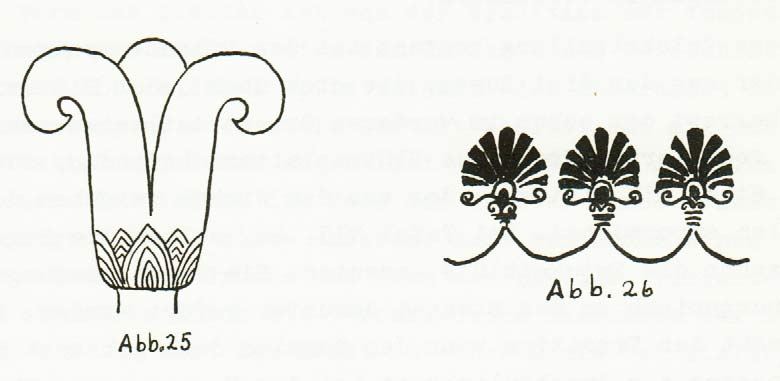

The blossom: Again, the blossom on the ornaments in no way resembles actual flowers. Instead it displays the characteristic features of a lotus viewed in profile, as derived from the Middle East or the Mediterranean universe.

| Here, in contrast, we have two spiral curls that do not match this idea of the lotus at all (panel IV, fig. 29, shoe on saddle, silver, engraved, and fig. 25). |

|

|

blossom motifs

|

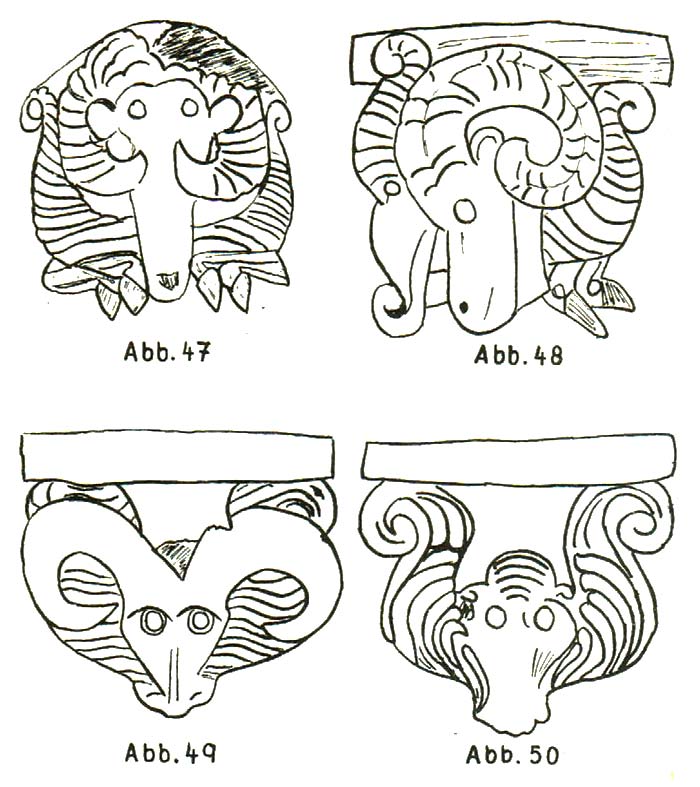

|