|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

|

- see more about craftsmanship and musical instruments

Drums in the African tradition bring the power that drives a performance. Music is not merely entertainment, but is rather ultimately bound to visual and dramatic arts as well as the larger fabric of life. Drums may be used for "talking," that is, sending information and signals by imitating speech. Many African languages are both tonal (that is, meaning can depend on pitch inflections) and rhythmic (that is, accents may be durational), giving speech a musical quality that may be imitated by drums and other instruments. Drumming music and dance are almost always an accompaniment for any type of ceremony: birth, marriages, work and funerals.

The presence of the drum has united the Black African and his spiritual concepts and ideas (ancestor cult). This instrument is irretrievably connected with the African societies because of its artistic and spiritual role and with everyday life in general. Many people are of the opinion that it is possible to have eng'oma ez'ensonga (this stands for an entire set of drums) speaking and talking for certain occasions. This belief is shown in the Ganda saying (dialect of the Baganda people). Ndi ng'oma, njogera matume: „I am a drum and I talk as instructed“ or ndi ng'oma, nseka matume: „I am a drum, I laugh as ordered“. Accordingly, the Baganda people (tribe having a kingdom in Uganda; belonging to the Bantu people) believe that playing the eng'oma ez‘ensonga constitutes a way to promote communication within the societies. It further represents an untouchable power, a centre of political, social and spiritual life of the Baganda people.

- more information on the Kingdom of Buganda and the Bantu tribes in Uganda: The Bantu people

The origin of the drum in Buganda

Information and knowledge on the drum has been handed over from one generation to the next one in the form of oral recollections and histories. Unfortunately, there have, as this is frequently the case with oral tradition, developed different stories, depending on source and on the different tribes involved.

- It is possible that the Bachwezi (people of the Bagwere) had introduced the drum, when they seceded from the newly founded dynasty of the Kingdom of the Baganda. It has been passed on that they had come with the drum.

- Bachwezi (Chwezi): According to oral tradition, they were supposed to be semi-gods; even if they were born of men and women, they did not die. They are portrayed as standing with one leg in the world and the other one in the underwold. They ruled the Kitara empire after the Babiito-Dynasty.

- Another tradition has it that the people of the Baganda have promoted the use of the drum in the Kingdom of Buganda.

- The name of a drum set has its origins in the Ganda dialect. Here is the story that tells of the formation of this name. The sound „ng'oma“ goes back to people collecting ants. If the people singing their songs encountered any white ants, there was dug a hole near to the ant’s colony, thus collecting white ants. If white ants left the hole, there was formed such a “ng'oma” sound near the digging. Even today, when people collect ants, they sing songs accompanied by the drum.

In earlier times, bigger drums were carved out of old hardwood trees. Today, these are made of pinewood boards and assembled like barrels. Smaller drums are laminated using a lathe, with a rope being attached for carrying. All drums have “heads” that are made of skinhides and that are attached by means of pins, which are forged into the sides of the drums. Within the drums there are arranged, as required by tradition, two ringing pearls as abalongo (twins) before the head is sealed by the skinhide.

- The Banyankore tribes in Ankole have clothing made of skinhides, especially the women, and when the time has come to perform music and dancing, pots are covered using the clothing, and they start drumming.

Throughout the entire African continent, the sound of nature is adopted, such as is the case in various other cultures. Wind, rain, thunder and lightning, animal sounds, etc. – these all have inspired societies in a creative and artistic way. Not without good reason, the Africans have “talking drums”, which are symbols of signalling as well as communication.

The importance of the drum in Buganda

There are two drums that are of eminent importance in the Baganda society: the embuutu (big drum) and the engalabi (long drum).

In earlier times, only men were permitted to play the drum in a community. Men used the doubleheaded drum embuutu and the long, cylindrical drum engalabi for men’s dances.

The saying ekiwumbya engalabi mwenge kubula means: a shortage of beer is the cause of sepsis in a human being. In former times, it was a taboo for women the drink the common beer or to participate in such drinking bouts. “Beer” was only reserved for men.

There were certain taboos for women in handling the drum. They were only permitted to use the double-headed fur drum embuutu, with which they accompanied such women’s dances. Women menstruating and breast feeding were prohibited to play the drum. One reason for restricting the women in terms of playing the cylindrical long drum engalabi was that the drum has to be held between the thighs, which was considered indecent. The most important ritual for women to play the drum that was permitted was within the palace, when the Royal orchestra dedicated a masiro to the king’s predecessors. This cult is still in use, especially for burial rites or initiation rites (customs and traditions).

Women have changed traditional standards and taboos, and they have started to play all instruments. Changes within the Baganda community were realized in colonial times, then turning upside down way of thinking and status quo. In schools and at universities, however, girls now are allowed to play all instruments, including the drum, also on the occasion of musical, dance and theatre performances. Social and cultural changes have triggered the course of emancipation.

Relations and interactions of the drum

Just like other tribal communities in Uganda, also the Baganda believe in the continuity of life after death. Origin in and birth into a certain clan and tribe constitute an essential part of every individual – to be born in order to live, to exist and to die. For this reason, everybody is expected to marry, to have a family, to raise children. A Ganda saying says: emiti emito gyegiggumiza ekibira – the future of every community is dependent on the future generation. A community will only have a future if man and women have a great number of children. The emburutu (female drum) and the engalabi (male drum) are co-existent and determine everyday life. The engalabi has to protect the female drum in everyday life, has to take care of it just like a husband protects his wife and children.

Drums within the communities determine dance and rites, supporting the communication in the form of signals. Drums are played in combination with other instruments, thus promoting unity. Drum ensembles performing are an integral part of daily life and not simply a popular tourist attraction. Every family owns at least one drum and is asked to participate in common drumming sessions.

On the municipal level, the different drums are brought along to be played on the occasion of performances. Within a community of drum players, the uniform performance is of uttermost importance. Playing the drum, however, is characterized by manifold variations, with all rhythms, however, still having a clearly defined line. By alternating hands and changing positions on the drumskin, there may be created different sounds. The role of the participants is decisive for every dual partnership (different hands and/or different sounds), creating the desired melodical rhythmical forms in the performance. It is the intention of the drummers to “create together a coherent sound” – for the dancer and for the audience.

Drums accompany man from birth to death

The sound of drums is first heard when a child is born, and the drums accompany every human being in the course of all events in his life until death.

Drums are played at the birth, at name-giving, when boys become men and girls grow into women, at courtship dances, at weddings, for seasonal festivities, during work, at harvest festivals, before a hunt, at family meetings or for spiritual reasons and, finally, at death.

The drum as an instrument of power

Restricting women in playing the drum had a rather significant influence on their exertion of power. The Kingdom Buganda was a patriarchally dominated community. Leadership and power within the family were exclusively in the hands of the male sex. Their most important institution, apart from the council of elders and the chief (clan leader), was the kabaka (king). As king, he was father of his people (tribe) and thus the source of all authorities. His instructions and penalties had to be gracefully and thankfully accepted. The association between the drum and the kabaka as leader and king may be expressed in the following words: omwana w'engoma (son of the drum). Indeed, when a new king is inaugurated, the Baganda people like to say: „alidde engoma“ (he who has eaten the drum).

Playing the drum has been used in order to gather the tribes in times of changes or upheavals of society, politics, and culture. Drums are played to unify meetings under the chairmanship of the kabaka (king). The drums are used to indicate affiliation to a tribe for rituals and on cultural occasions during his reign.

There was created a number of taboos in order to prevent the drum as an instrument of power from being improperly used or misused. Taboos further are intended to keep the drum holy, like symbols standing for power. Due to the power of the drum, drums have to be regarded with respect, and they must not be improperly used. A drum must not be placed on its head, as drums are only arranged on their heads if a kabaka (king) dies, then representing a symbol of sorrow and grief.

Misusing the drum was considered disdaining the power of the kabaka. Taboos in the connection with the drum, furthermore, are: drums that are stored in the kitchen in a house; inhabitants have to be individuals without being in a relationship, as otherwise the drum could be broken; married dancers have to refrain from sexual intercourse one day preceding their performance, as otherwise the drum will start to crack or the performance will not be as desired; there is to be guaranteed that a magical defence means is arranged in the inside of the drum (provided with two pearls – magical power) against competitors, jealousies, etc.; a mother still breast-feeding is not allowed to ever touch the drum as this would definitely decrease the magical power of the drum.

One of the most famous drums, which is able to represent the superiority of the power of the kabaka (kings) among the Buganda people, is the drum mujaguzo. The designation has its origins in the Ganda dialect kujaguza, meaning “anniversary”, indicating the origin of the drum.

The Lion Clan used to play a smaller drum, the so-called nalubare, indicating the holy shrine of King “Kintu” on the hill Magonga in the district of Busuju. This drum had been fabricated by a certain Mukulu Kasimba for Kintu himself. The story goes that the origin thereof also was the mujaguzo drum. The drum set for the king consisted as follows of: timba-one ngalabi, kawulugumo (a long drum), namanonyi (a big drum), nkonyi (four medium-sized drums), njawuzi (five mediumsized drum), njuyi (25 small to medium-sized drums).

The mujaguzo, hence, forms a set of more than 50 drums, which were arranged at the royal court on the occasion of the prince being born, if the king travels his realm and if he „goes into the forrest“, a euphemism for his death, as in the Ganda tradition there is not said that the kabaka (king) has died. .

Of all drums, the mujaguzo plays a special role at court and in the entire kingdom, representing power, political supremacy, cultural importance and foundation and establishment of the kabaka realm (kingdom).

The inviolability of the drums may be made out in the way they are played, transported and kept. Those who are especially in charge of taking care of the drums, “the head of the Bagoma ba Kabaka”, are called Kawula. The royal musicians and dancers have to be unmarried males, who have not become men yet, as a young boy only becomes a man when he marries and fathers children.

The drum as a clan’s identity

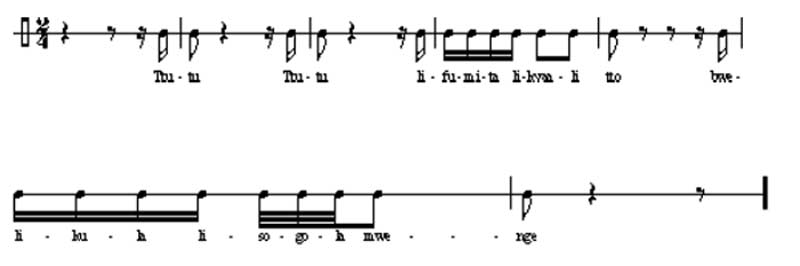

In the Kingdom Buganda, the clans form the basis thereof. Every single clan has its name and its own geographical location, which is designated as clan headquarter. The form of a clan identity is identified by a mubala (drumbeat), has its own drum rhythm, which is unique in regard to other ones. Please find transcribed that of the Lugave clan (pangolin monkey):

(Transkription by Ronald Kibirige)

The drum rhythm verbalizes this Ganda text, which is used in ttutu ttutu lifumita likyali tto bwelikula lisogola mwenge (the spear – a still very young blade of grass, still growing) when producing the local Ganda brewing (beer).

Clan rhythms are rather diverse. On the one side, they show the clan’s identity, and on the other one, they have a meaning that is inseparably associated with a certain clan. Depending on the clan, drum rhythms ask the members of the clan to start working, to conserve nature, to give mutual respect, to maintain moral standards, to save the environment, to marry and to take care of the family and to beget children. For example, the above transcriped drum rhythm asks the male and female members of the Lugave clan (pangolin monkey) to marry and to have children, while still able to reproduce, as this constitutes one way the clan and the realm are based upon and may be strengthend with.

The kingdom of Buganda comprises 52 clans and each has its own totem – among others: Kinyomo clan, Nkusu clan (parrot) and Mbogo clan (buffalo).

The drum as a means of communication

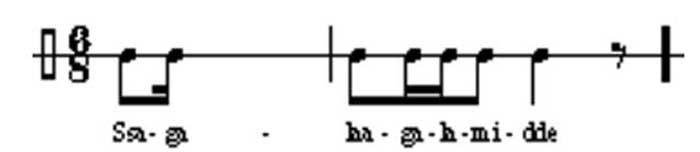

The drum is also used as an instrument for mobilizing the community in the course of worshipping (ritual ceremonies), healings and dances; it communicates information in a remote way. While TV or also radio are predominantly a means of entertainment, which, however, is still non accessible to many rural communicties, here the drum is still of greatest importance. TV and radio are expensive and dependent on electrical power. The media sector is still privately owned, focused intently on turnover. It is not possible to offer this service to a poor rural population “free of charge”. The information that is communicated by these media does not have an inter-action between that presented and the people, who are then simply reduced to being consumers. Communities without access to radio, TV or other means of telecomunnication (mobile communication network) still need the drum as a medium of communication. Using drum rhythms like ssaagala agalamidde (everybody is to get up) or bulungi bwansi (cleaning of streets and wells) the inhabitants are asked to do so or participate by means of the drum. Leading a community sounds like: ssaagala agalamidde, which are beaten at various points in the neighbourhood, in the neighbouring village and preferably at a cross-section.

(Transkription by Ronald Kibirige)

Due to the above description, the drum does not decrease in its importance as a means of accompaniment of social and collective responsibility. The drum transforms signals and transfers information within a society.

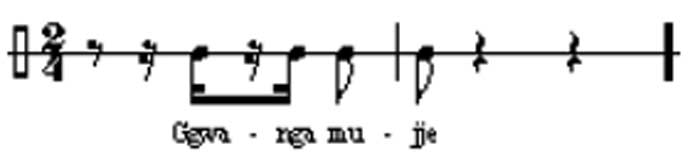

Events may be communicated by means of the drum within a society or community in the case of insecurity, crimes, death, accidents, loots, etc. In such cases, the tragic events may be communicated by members of a community therein by way of drum beating. In this way, it is possible to call for support or help of any kind. This communcal cohesion within the community is represented by ffe mwe, mwe ffe (they are us and we are them), the obligation of every single member of a community to provide help if there is danger to members. Ggwanga mujje (come to my / our rescue) is the content of this drum rhythm, there is, however, not indicated any prevailing danger. As soon as this drum beats are heard, all members of the community have to be ready. In order to guarantee that help and support are provided, every family is asked to keep ready a drum including drum sticks. Transcription for this ggwanga mujje rhythm by Ronald Kibirige:

Also village churches used the drum for cummication. Churches that are distributed rather far away from each other use the drum in order to communicate the beginning of their services. The drum calls the community to church service. During the service itself, the drum is used to play hymns.

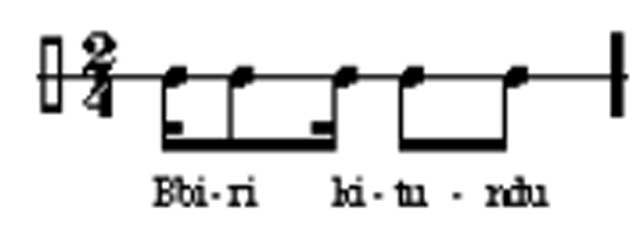

The drum beat bbiri kitundu (it is 8:30 o`clock) was important for the priest or the person commissed by the church to be in charge of conducting the church service. This rhythm at exactly 8.30 o`clock in the morning is supposed to remind the church goes to get ready for church service at 09:00 o`clock. The drum verbalizes time, as it is a saying in the local language of the Ganda.

(Transkription by Ronald Kibirige)

The drum and spirituality

The Buganda believed in superhuman spirits. Balubaale were men who carried those deceased over into death. Mizimu were the ghosts of dead people. They believed that the soul lives on. The supreme power was the Creator, Katonda. Some other Balubaale (about 37) had very specific functions; there were the god of the sky, god of the rainbow, god of the lake, etc. They built for them all special shrines or temples. Temples were

served by a medium or a priest who had powers over the temple. They also believed in spiritual powers, particularly witchcraft, thought to cause illness and other misfortune. People often wore amulets (charms) to ward off their evil powers. The most significant spirits were the Muzimu or ancestors who visited the living in their dreams and sometimes warned of impeding dangers. The Balubaale cult no longer exists. The belief in ancestors and the power of witches, however, is still quite common.

Dance and music having drum accompaniment at ritual sites amasabo (shrines). Spirituality constitutes an important feature and characteristic of the Buganda culture, still being practiced today. The Baganda people worship their gods; Kiwanuka for children, Mukasa for fishermen, Ddungu for hunters, Kibuuka for warriors, etc. Africans believe in spirits and ghosts living in different areas, being active and having their importance and reason. They build altars (shrines) for their gods, where they present them with sacrifice gifts. Such shrines are equipped and maintained by priests, fortune tellers, media and other spiritually gifted people.

The drum is one of the instruments that cover an important aspect in the ancestor worship of the Baganda. It is an accompaniment to such worship processes. A shrine ritual is never celebrated without drum accompaniment. A fortune teller or preacher is not able to perform such ceremenoies without drum accompaniment. The drum presents a medium between the world of the visible and the world of the invisible. During a worship process there are played all drum rhythms in order to call the ancestors or also the gods / deities and spirits; all are to come to this ritual site and participate in these praisals. It is the drum, which seeks to establish a connection with the spiritual world in the course of such invocations and prayers.

Drums are further used for therapeutical purposes and for healing. Also people having emotional, psychological and mental disorders seek support with healers playing the drum. Herein, drum rhythms are used in the form of sound therapy in combination with songs. The patient is to actively participate by way of music and with the help of the healer in such session. Using the songs and the drum, the patient is to be scanned, thus recognizing his/her illness/disorder, wherein all the spirits and ancestors necessary are invoked to participate in the healing process. The patient, however, often goes into a trance, too. This type of therapy is used to cure and heal people having psychological disorders but also in the case of stress, infertility, etc. For this reason, the drum is considered a mediator of these persons, trying to bring them back into life, into a daily routine, to free them of their problems and their aches and pains, and to bring them back into community life.

Apart from traditional rituals in the community, the drum is nowadays also used in the church service. The missionaries described such indigenous music and dances as heathan and pagan practices, defining them as being satanistic and excessive. Such rituals and rites did not correspond to their ideologies, which is why they were originally forbidden.

The drum, however, was the first traditional instrument to enter church practices. The drum, however, was re-contextualized for church-internal contexts, the style of playing was modified, and adapted to the festive sites.

Whereas the secular dance Baakisimba is loud and is performed in a solemn and ceremonious mood, church has restricted this dance to certain motives. The drum, as traditionally required to have two sounding pearls, these magical symbols, was prohibited. After the drum being accepted, it was subsequently used for ecclesiastical music and church songs, and it was finally introduced, in the local language and accompanied by traditional instruments. Traditional melodies were provided with new texts.

This shift in conception made church service more accessible to the indigenous population. In Buganda, a drum rhyhtm was named abasaseredooti balya bulungi, balya bisiike, nebamala bagejja (the church priests eat well, they eat fried food, this is why they look so healthy). In this way, the position and the status of the church and those of the priests was increased, which finally brought about the inviolability of the church as an institution.

The drum accompanies the dances of the tribes

African music is nearly always coupled with some other art form, such as poetry, ritual or dance, and it constitutes one of the most revealing forms of expression of the African life and soul. They have a sense of rhythm. Some tribes combine dance and music, and they explain history and the social elements in a form like the theater of today. Dances were most of the time closely related with religion, ancestral worship and spiritualism. We have to understand that there is an interaction between social and cultural background within different communities in Uganda. Every community or tribe has its own religious beliefs. All rituals are organised, with dances being performed by communities in order to worship or appease the gods, in order to ask for a good harvest before sowing, at the occasion of midsummer or midwinter festival, or just on the occasion of entering a new lunar phase; or if there was need of rain. The gods were asked for fertility, or the people tried to appease the demons or diminish their influence. Everybody was invited to be present to honour the situation and to thank the gods.

These dances are part of everyday-life, they are old traditions, handed down from generation to generation, with a deep cultural background being present in a ceremony or a ritual to thank the gods, or they can constitute a local social interaction, such as the wedding party or the burial ceremonial for an important personality; courtship dance to bring together the new pairs, or ritual dances for a boy becoming a man; or it could simply be a gathering leading to a party with dance, or there has been arranged a party for guests, etc. Dance is also expression of joie de vivre.

The most frequent form of using the drum was the dance of the tribes and for the communication within the community and the communes (villages). Dance and music were an integral part of tribal life, starting with birth, determining everyday life and finally ending with death. The importance the dance is based upon offers space for the release of emotions by way of music. The dance may also serve as a social and artistic medium for communication. Thoughts and ideas may convey a personal and social importance and meaning through the selection of movement, posture and facial play. Through dance, individuals or social groups may express reactions to certain events, may display their attitude and approach to hostility, co-operation, friendship or rejection. In this way, they express their respect and gratitude to their superiors as patrons and benefactors. They may react to the presence of competitors, may confirm their status as inferior or superior, may support their ideas and conceptions by chosing the appropriate phrasings or symbolic gestures.

In Buganda dances are rather popular, namely: Baakisimba, Mbaga, Maggunju, Nankasa, Muwogola. All the dances mentioned are accompanied by drum and instruments including vocals at the royal court.

Baakisimba – a court dance at the royal court, wherein the engoma‘s (drum set) were the most important accompaniment and directed until the middle of the 20th century by two drums, this is the embuutu (big drum) and the engalabi (long drum). The embuutu is a big, conical doublemembrane drum, whereas the engalabi is a long hand drum, provided with a single membrane and an open lower end. The engalabi syncopates the rhythm, whereas the embuutu initiates the main melody. Two further drums have beein integrated in the set. The empuunyi (bass drum) having the lowest pitch gives the central beat and determines the tempo of the dance. The two namunjoloba (small drums) were also included for decoration and facilitation; for playing, there are used two sticks, and these are in charge of directing the dance flow by initiating transition signals.

- Empuunyi - bass drum

|

- Namunjoloba - small drum

|

Maggunju is a dance danced at the king’s court, which is strongly marked by melodical drum accompaniment and rhythmical patterns. In the Maggunju dance, a rhythm pattern is combined with texts. For example, the two big drums embuutu (big drum) and empuunyi (bass drum) produce nkutte mu nsawo, nkutte mu nsawo, nkutte mu nsawo eya Ggunju neeya Kasujja (I have tried to touch Ggunju and Kasuujja). This drum rhythm is intended to present the common attempt of the two girls, Ggunju from the Butiko clan (mushroom) and Kasujja from the Ngeye clan (Kalebasse monkey), which accompany the dance.

The development of the Maggunju dance goes back to the reign of Kabaka Mulondo in the year 1555. The small drums (namunjoloba) also create a coded rhythm ensuku zaffe bbiri zeezatuwonya enkolo leka nneesulike ondabe (which accompanies the two girls Ggunju and Kasujja), from whom Kasujja is chosen to become the wife of the Kabaka Nakibinge.

The Mbaga dance is only accompanied by two drums, the embuutu (big drum) and the engalabi (long drum). These two drums represent the male and the female form (a discussion thereon is the frame within the dance). The dance is performed during the wedding ceremony. This Mbaga dance is exclusively performed for freshly and already married couples. It is known for its elaborative and narratively sensual gestures and is to communicate sex education. The two drums (engalabi and embuutu) dictate gestures and movements for this Mbaga dance. The dancer-girl represents patterns and structures to this poly-rhythmic drum beats; movements with waist, leg movements and arm gestures are emphasized.

For all traditional dances of the Baganda, the drummer is stimulated to indulge in creativity – with a mixture of vocals and clapping (engalo), dictating the dance steps for the male or female dancers, requiring good communication and co-ordination between the different drummers. For the drummers it is important to pay attention to their entry, to keep the tempos and pitches and simultaneously to improvise and introduce interesting turns or changes. The drive has to be perfectly attuned, and the drum sets are determined for an appropriate tempo for the dancers, wherein this may sometimes be rather different from vocals, and there is still enough space for the next drum entries. The instrumental accompaniment acts as life energy for the dancer in the form of tempos, energy and kinaesthetic quality (motion), which are then combined to the overall performance.

- see more information about Traditional instruments of the Uganda people and Traditional dance of the Uganda people

Drum - an archive of the language

Nannyonga-Tamusuza (2005) has found that the "Ganda music“ (of a people in the Kingdom of Buganda) is deeply rooted in the practiced language (Luganda). In each play, there is existent a text. The drum is considered the custodian of the Ganda language, of the Baganda people. These are texts that are still preserved in the drum rhythms. An example: the embuutu simulates various sounds of Uganda – in various pitches when the drummer beats these and in corresponding rhythms, having the appropriate hand position and with beating the drum in the correct position. The timbre of the sound of the drum reacts to the beat onto that position where the hand meets the drum. Sounds may be produced by scratching, crackling or stroking. Scratching or beating the drum with the hand or with sticks will produce different combinations of pitch, timbres or rhythmic patterns; in this way, there is produced a verbal form of the text that is not directly recognizable.

Drum rhythms are not simply sounds but there are rather contents being transmitted by way of the language of the drum, which then emphasizes the meaning with its spiritual understanding of the community. Communication and comments are realized by way of the drum, which is considered the secret language of Africa (talking drums). The drums in Africa are used as a form of inter-regional communication among tribes. In Africa there are more than 2000 different languages and dialects being spoken on this continent. In earlier times it was not possible to directly communicate in these languages, and for this reason the drum became a means of communication. The drums were not able to translate a message directly via the rhythm. Beating the drum is considered supplementary to the inter-action of a reciprocity between right and left hand, being relevant in terms of music. This complementary expression of beating the drum is a melodious interplay, wherein each hand, in a remarkably recognizable way, contributes to rhythmic and melodious sounds and tunes. It obviously is not possible to play such a drum melody single-handed.

In Buganda the embuutu (big drum) defines the rhythm in accompaniment to the Baakisimba dance abaakisimba b'ebaakiwoomya (the people who have made a banana juice from this sweet banana shrub, which becomes alcoholic in the fermented state). This text is beaten with both hands and played by scratching on the membrane. The text tells of the development of this dance. There is assumed that the Baakisimba dance has its origins at the court of the king, when the kabaka (king) and his subjects got happy (this is, drunk) by drinking this fermented banana juice (in Buganda, however, a kabaka must not get drunk). After the festivities had ended, the kabaka started dancing and praised his subjects, telling them that he loved this banana shrub and the fruits, from which this wonderful and sweet banana juice was produced. The speech of the kabaka, abaakisimba b'ebaakiwoomya (those who have produced from this banana shrub such a bronzecoloured, sweet juice) was integrated in the drum rhythm of the Baakisimba dance. The text further praises the agriculture in the kingdom, which represents the backbone thereof and is to be promoted.

Conclusion

The drum has a rather special position in the social, cultural and political ideology of the Baganda people. The centrality of the drum is visible in the Ganda saying ekibi kikira engoma okulawa (Sin is better than the destruction of the drum). The drum unifies the community consisting of clans, signals death, danger and happiness. It unifies people under a leader in various levels with the kabaka (king) as their central power. The drum conveys the identity of an indigenous, social structure with clan systems, which form the basis of the community of the Baganda people, to the tribes. Playing technique and rhythm are part of all social, cultural and religious systems of the Baganda. Nature and power of the drum represent with the culture of the tribes the developments thereof as well as social changes. The power of the drum constitutes a common feature in urban as well as rural communities and societies ndi ngoma nnene (I am as powerful as a drum). In this way, there is expressed an individual identity as well as bravery and valour within a group.

© Albi Face Music - March 2013 - revised and translated by Hermelinde Steiner

|