- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

Below you find enlargements of map sections – do click on these and enjoy the view!

© Albi - Face Music 2007

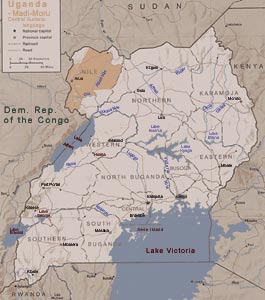

- The Madi - Central Sudanic language

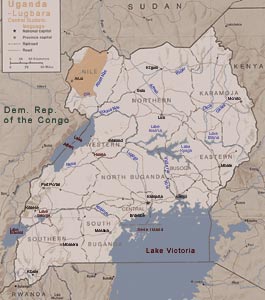

- The Lugbara people

Mythology - All are descendants from the first creatures put on earth by spirit (the creator of men) at the beginning. Spirit created a man (gboro-gboro) and a woman (meme), and then domestic livestock. Meme had wild animals in her womb, so that after the gazelle had broken out, all animals followed. She also bore a boy and a girl, who reproduced themselves in pairs later on for several generations, till the Lugbara heroes, Jaki and Dribidu were born. Adroa appeared in both good and evil aspects; he was the creator god and appeared on earth as a human who was near death. He was depicted as a very tall and white man with only one half of a body, missing one eye, one leg, etc. His children were called the Adroanzi. They were nature gods of specific rivers, trees and other sacred wild areas. At night, they followed people and protected them from animals and bandits as long as they did not look over their shoulder to ensure that Adroanzi was following; if the person did so, they promptly killed him or her.

Religion - They believe that the living and the dead will be of the same lineage and are in a permanent relationship with each other. As a result, the dead are aware of the actions of the living and care about them, whom they consider as their children. However, in some circumstances, the dead send sickness to the living in order to remind them that they are acting custodians of the Lugbara lineages and their shrines. God is also associated with that relationship between the living and the dead. He is the creator of men, who long ago created the world. However, he is conceived as god in the sky, remote and good (Onyiru), and as god in the streams, close to people, and dangerous 'bad' (Onzi). While god created the world, the hero-ancestors and their descendants, the ancestors, formed their society.

History - In their location in the Nile region, the Lugbara have been subject to only sporadic colonial administration since 1900, even though the area had been leased by the British to the Etat Independant du Congo since 1894. Some Arab expeditions entered in this region in the past; however, the Lugbara were not touched by the slave trade. The Belgians advanced through the area in 1900, opening a post at Ofude, to the west of Mount Eti, that lasted for several years. Followers of a prophet, Rembe, a Kakwa living about forty miles north of Lugbara, were subsequently entrusted by the colonial administration with overseeing the relationship between the Lugbara and the colonial authorities, creating powerful chiefs that had never existed before in Lugbara. In 1908, and after the death of the Belgian King, Leopold II, the area became part of the Sudan. By 1914 the southern portion of the Lado Enclave passed to Uganda, and a station was built at Arua. The Africa Inland Mission and the Roman Catholic Verona Fathers (Comboni Missionaries) arrived in the 1920s, they opened schools, and large missions staffed by Europeans.

Symbols - Shrines to the ancestors constitute one of the visible signs of Lugbara religion. There are many different kinds, the most prominent ones, however, being those erected for a ghost of an ancestor (Orijo, or ghost house). They are made of pieces of granite formed into a house and placed under the chief wife's granary. As a ghost spirit can create trouble for the living, he can have several shrines, where sacrificial food and beer can be offered by his descendants living in a particular compound. Other shrines include those built for the ancestors, shrines for those who did not leave sons behind, shrines for the ghosts of mother's brothers, and also for women of the lineage. Stones, as part of a shrine built to the ancestors, also constitute important symbols of wealth and prestige, and they are inherited by a person's sons after his death.

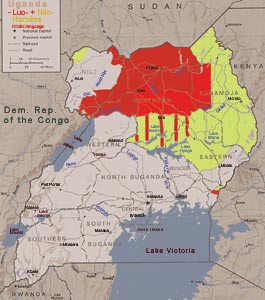

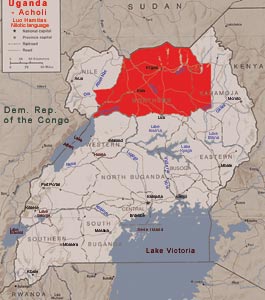

- The Hamites - Nilotic language

The Acholi, Langi, Alur and some other smaller ethnic groups belong to the group of the Western Nilotic language, all together making up about 15% of the overall population. Most of the West Nilotic languages in Uganda are called Lower Nilotic, and they are closely related to the language of the Luo in Kenya. The two biggest ethnic groups, the Acholi and the Langi, speak nearly identical languages. Acholi is situated in the northern region of Uganda, this constituting also the home of the Acholi tribe. Its centre is Kitgum town. The tribe is a mixture of Negroids and Hamites. The Alur, who live in the western areas to the Acholi and the Langi, have a similar culture as the neighbouring societies of the West Nile area, where the majority of the people speak a Central Sudanesic language. The area West Nile is situated in the northwestern part of the country, where the tribes of the Kebu, Ondrosi, Lugbara, Kakwa and Alur have found a home, with their origin going back to the Hamites. The centre is the town Arua.

The tribes speaking a Nilotic language (Hamites) are in Uganda generally dinstinguished into the following groups:

| - The Luo - the River-Lake Nilotes: Acholi, Alur, Jonan and Jopadhola |

|

| - The Nilo-Hamites (Plain Nilotes): Karimojong, Iteso, Kumam, Langi |

|

| - The Higland Nilotes: Sebei |

- The Luo people

The Luo are part of the people from the southern Sudan. The migration brought changes during the 15th century with the Acholi people and with intermarriage. The Langi lost their Ateker language and migrated closer to the Lake Kyogo in the 18th century after living more than two hundred years in the Acholi region. They lost the system of pastoralism and began to speak Luo. Their origin were not the Luo but rather the Nilo-Hamites.

The Luo marked the last influence on the already settled population in the region in the West Nile and in northern and eastern Uganda. They introduced their language, culture and some animals and crops. The concept of the empaako name is of Luo origin, hence is the system of centralised states. They founded the Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom that was established after the collapse of the Bachwezi dynasty. Most of the West Nilotic languages in Uganda are called Lower Nilotic, and they are closely related to the language of the Luo in Kenya.

- The Acholi people

The Acholi practise no circumcision. Patterns with ornaments are tattooed on chest and stomach. For all men, even husbands, it is forbidden to touch the women's tails. Women are very respected for their independence and pugnacious nature, their honesty and their sexual morality. There are more women than men, and thus they are naturally inclined towards polygamy. Practically no woman lives unmarried her whole life. When she has lost her husband, she offers herself to a new one to get married.

The Nilotic marry normally outside of their clan. Girls are betrothed at the age of six or seven, and their selected future spouse continually makes small presents to his father in-law until the bride becomes of nubile age. It is regarded as shameful if the girl is no virgin on her wedding day. The groom will then send her back to her parents, who then have to return the brideswealth and have to pay a penalty. The wife's adultery was formerly punished with death, and the capital penalty was also inflicted on young men and girls guilty of unchastity. They had to pay twenty sheep and two until six cows in total; the husband elected can claim his bride when he has made half of the payment. If a women cannot give birth to children in her life, the amount of her purchase is returnable by her father, unless the widower consents to replace her by another sister. The women are prolific, and the birth of twins was considered a divine miracle. This is considered a lucky event, and this occasion is celebrated by feasting and dances. The parents of the infants must stay in the hut for a whole month.

The act of naming a baby was of essential importance after birth. Names are not male or female, and a daughter often bears her father's name. The details or situation of the birth were therefore substantial. Otto means that many sisters and brothers have died. Oketch means giving birth during cultivating the land. The name Odoki was given when the mother has returned to her parents. Bongomin means that there are not brothers or sisters. Olanya states that the mother has left the child. If a woman gave birth to twins, this was seen as a "divine" sign. Normally, an elder woman (Lacol – midwife) helped with the birth. In case of an emergency, the medicine man (Won Yat) was called to help. Deformed children, who did not have a chance to survive, were drowned in the river, with this being presented as an accident.

If the first wife of the deceased is still alive, he will be buried in her hut, if not, beneath the veranda of the hut in which he has died. A child is buried near the door of its mother's hut. A sign of mourning is a cord of banana fibres worn round the neck and waist. A chief chooses, sometimes years before his death, one of his sons to succeed him, often giving a brass bracelet as insignia. A man's property is divided equally among his children.

They erected shrines (Avila) for the representative of the people, the so-called Jok. All rites as well as spiritual acts and worships were performed in the immediate surrounding of such shrines. They also worshipped this Jok as god and father of the people, who has come down from heaven and turned into a man. Additionally, they also worshipped the Dark Power, the devil, who was called Lubanga. Unfortunately, the Christians have used this name for the translation of God.

The legend says that the first man was called Luo; his father was the god Jok and his mother was Earth. In the family, there was a son with the name of Lagongo. He carried bells around his hips and ankles. His hair was decorated with feathers, he used to dance the whole day long. He had magical power. As his mother did not know who his father was, the story went that she had been made pregnant in the bush by Lubanga, the devil.

Neighbouring tribes to the southern are suspects, totemically. The religion appears to be a vague ancestor worship. In general, the Acholi have two other gods, called Awafwa and Ishishemi, the spirits of good and evil. To the former, cattle and goats are sacrificed. Similar to their neighbours, the Bantu, they have great faith in divination from the entrails of a sheep. Nearly everybody and everything is similar ominous of good or evil. They have few myths and traditions, with the ant-bear being the chief figure in their beastlegends. They believe in witchcraft and practise trial by ordeal. This is due to their fecundity and morality.

Those who live in the low-lying lands suffer from a mild malaria, while abroad they are subject to dysentery and pneumonia. Also epidemics of small-pox have occurred. Native medicine is the simplest. They dress wounds with butter and leaves, and in the case of an inflammation of the lungs or pleurisy, they pierce a hole into the chest. There are no medicine-men - the women are the witchdoctors. Some of the incisor teeth are pulled out. If a man retains these, he will, so it is thought, be killed in warfare. Among certain of these northern tribes, the women also have their incisor teeth extracted, otherwise misfortune would befall their husbands. For the same reason, the wife scars the skin of her forehead or stomach. Before starting on a perilous journey, even the Bantu husband cut scars on his wife's body to ensure him good luck, and he arranges a ceremony in the sacred burial place of the tribe. The grave is dug beneath the veranda of the hut.

Both men and women work in the fields with large iron hoes. In addition to planting sorghum, eleusine and maize, tobacco and hemp are both cultivated and smoked. Both sexes smoke. But the use of hemp is restricted to men and unmarried women, as it is thought that this might injure child-bearing women. Hemp is smoked in a hubble-bubble. They cultivate sesam and make an oil from its seeds which they burn in little clay lamps. These lamps are of an ancient saucer type. They make salt, effected by burning reeds and water-plants and passing water through the ashes; furthermore they practise the smelting of iron and ore (confined to the Bantu tribes); pottery and basket-work. They live in strong stone-walled villages. Some huts are partitioned off to provide for a sleeping-place for goats, and also the fowls sleep indoors in a large basket. Skins form the only bedsteads. In each hut there are two fireplaces, about which a rigid etiquette prevails. Strangers or distant relatives are not allowed to pass beyond the first fire, which is near the door and is used for cooking. At the second, which is nearly in the middle of the hut, sit the hut owner, his wives, children, brothers and sisters. Also the family sleeps around this fireplace. Cooking pots, water pots and earthenware grain jars are the only other furniture. The food is served in small baskets. Every full grown man has a hut to himself, and one for each wife. Father and sons eat together, usually in a separate hut with open sides. Women eat apart therefrom, and only after the men have finished. They keep cattle, sheep, goats, fowls and a few dogs. Women do not eat sheep, fowls or eggs, and they are not allowed to drink milk except when mixed with other things. The flesh of the wild meat and leopard is esteemed high by most of the tribes. Beer is made from eleusine.

The Acholi were excellent hunters, with the prey enriching the daily menue. They lived on a mixed economy, land cultivation and livestock breeding. They hunted in different ways: either as a group or alone as trappers (Okia); they used nets, pits, or they hunted the animals into the water and subsequently killed them with their spears.

The Acholi are considered to be peaceful people, but good fighters. Their weapons are mostly spears with rather long flat blades without blood-courses, and broad-bladed swords. Some use slings, and most carry shields. Bows and arrows are also used; firearms are, however, displacing other weapons. Warfare was mainly defensive and intertribal, this last a form of vendetta. If a man had killed his enemy in the battle, he shaved his head on his return and he was rubbed with "medicine" (generally goat's dung), to protect him from the spirit of the dead man. The young warriors were made to stab the bodies of their slain enemies.

Acholi folk music is, like most Ugandan music, pentatonic. It is distinctive with choral singing, in parts with a lead voice. Songs are also accompanied by a string instrument, the harp-like adungu, and numerous percussion instruments.

The vocal lines of the songs of men and women are in polyphonic style, and they tend to create a counter-point effect. Songs are performed at various occasions. The singing is melodic, and dances are performed collectively. Solo dancing is rather rare. The Acholi have various kinds of dances:

Various dances are performed on certain occasions like, for example, birth, funeral, wedding, rituals (ancestral worship, beginning of a hunt, victory over enemies) and the celebration of the seasons (for example, thanksgiving).

| - Apiti was only danced by girls. The men were not admitted. The girls danced in a line and sang. It was a dance which was danced in the middle of the year, when it was raining. |

|

| - Atira was a war dance. Fighting scenes were performed with spears and shields. |

|

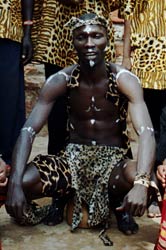

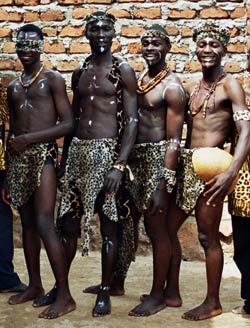

| - Bwola is a court dance (in the king's palace) of the Acholi, who live in the north of Uganda. This is a circular dance that is performed by the older men and women, and the circle represents a fence that surrounds the palace court. Many events and conversations take place during this dance, so it may last for many hours. The main dancer is mostly dressed in a leopardskin and conducts the scenes. The men carry and beat the drum. This dance is a very rhythmic one. |

|

| - Ding-Ding dance is performed by the young girls of the Acholi, and their movements are meant to imitate birds. The girls dance to attract the young boys, so the dance is usually held on bright days, when the sun is out. | |

| - Ladongo was danced after a successful hunting event. Men and women danced in one line facing each other, with clapping of hands and running up and down while jumping. |

|

| - Larakaraka is a ceremonial dance of the Acholi, who have borders with the Sudan. It is primarily a courtship dance that is performed during weddings. When the young people in a particular village are ready for marriage, they organise a big ceremony where all potential partners meet. As a sign of friendship, food and alcoholic drinks are served during this ceremony. Only the best dancers will get partners, so there is a lot of competition during the dancing. In Acholi, if you are a poor dancer, you are likely to die as a bachelor. |

|

| - Lalobaloba is performed without drums. The people dance in a circle, with the men building up the outer circle and putting their hands on the girls' heads. The men held sticks in other hand. |

|

| - Myel Awal is a funeral ceremony, in which the women dance around the burial site and the men make up the outer circle with spear and shield. |

|

| - Myel Wamga: Men set in circles on the floor and played the harp (ennanga), while the women danced the Apiti. This dance was performed on the occasion of weddings or beer festivities. |

|

| - Otiti: Dance in which the men carry spears and shields. The drummers are arranged in the middle, and the people dance more than they sing. |

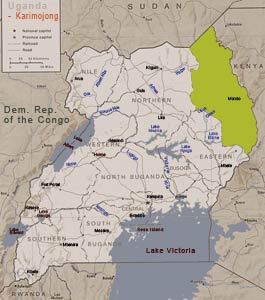

- The Karimojong people

Before a boy could announce his intention to marry, he had to prove to the elders of the village that he was ready to become a man. In early times, the young man had to set out alone only with a spear and to hunt. He had to present the animal‘s tail. Nowadays he has to search for cattle to pay the bridewealth. Upon his initiation of manhood, his father had to present him with a bull which was then slaughtered and the meat shared with his boyfriends. During the ritual the young man would smear himself all over with dung from the entrails of the bull. His hair will be cut by one of his friend. In this moment he had attained the marriageable age, und with the permission granted by the elders he could wear ostrich feathers on his head. His father will instruct him, and he would have to look for a girl to get married. The young man would make his choice and inform the father who would have to pay the bridewealth.

As soon as the bride arrives in the groom’s home, the ceremony would start with a dance and people began to gather in the cattle kraal. The Karimojong were polygamous, with the number of wives only being restricted by the man’s possibility to pay the bridewealth. Marriage between close relatives was prohibited. If there had been agreed on a divorce, the bride could return to her father’s home and the bridewealth would have to be returned, also including the bull. Afterwards she was a free woman again. Sexual intercourse among unmarried men and women was frowned upon, and a pregnancy resulting from such an act was decried. A bridewealth has to be paid to the woman’s father, and the young man has to marry the girl. The issue of adultery was in fact a family affair, not a personal one; and the property which was confiscated from the dulterer would be divided, as a kind of penalty, among the members of the affected family. When a woman was to give birth, her sisters would come to assist. The women acted as midwives, they would wash the baby with cold water. On the day when the woman ended the days of confinement, a ritual ceremony would be performed. Children were given the name of the ancestor, meaning that the first born gets the name of the grandfather, the second one that of the grandmother, the third of a great aunt or uncle and so on. This implied in effect that they did not have particular names for the different sexes (no particular names for girls or boys).

When a village member died, it was allowed to start weeping. The elder of the village was buried in the centre of the calf or sheep kraal, with his head pointing to the north, because they believe that they came from the north. The body was covered with cow dung, followed by soil and then stamped on. A large stone would be placed upright on the grave. Death and burial ceremonies tended to vary from clan to clan but generally all the mourning and weeping would proceed for a couple of days. All the relatives would come, and if the deceased had brothers, they would inherit his wives and part of the wealth. Some clan did not bury the body but rather left it for nature.

They do not worship for the sake of it. In times of troubles, sickness or misfortunes, the clans would gather together at the ancestor‘s grave with all their children and grandchildren. There they would milk the cow, bring up the tobacco and slaughter an ox. The contents of the ox‘s stomach were smeared over the people and over the burial stones.

If rain failed to come, elders would approach the emurron (medicine man) with a present of a calabash of milk and impress upon him the necessity of making rain. Then the akirriket (rainmaking ceremony) started. All the elders would gather at the appointed spot. A man was then to kill the bull by spearing it in the side. The bull was slaughtered, and the meat would be roasted on the fire.

A devastating cattle plague swept the area in the late nineteenth century, a tragedy that showed the young to move to grazing areas in the highlands. Grazing areas are common ground outside the stockade, although milk cows sometimes stay near the homestead. During the driest months, usually February and March, cattle are moved to seasonal camps some distance from the homestead. In these camps, men live almost entirely on milk and blood drawn from live cattle, and, occasionally, meat. In the homestead, women, children and old people forage for food, including wild ducks, if stores of grain are depleted. Milk is reserved for children and calves, only then it would be consumed by adults.

Men living within a homestead are related by descent through male forebears. This group, the patrilineage, is augmented by wives and children, and occasionally by unmarried brothers of the lineage head. A group of brothers usually shares the ownership of a herd of cattle; cattle are usually branded with clan markings, although a man normally knows each animal in his family herd. Only when the last surviving brother dies is the herd divided among the next generation, with each set of full brothers inheriting a small herd.

Two important sources of social solidarity link members of unrelated lineages to each other. Intermarriage forms bonds based on bridewealth, cattle which is given by a man's family to that of his bride, and children, who are important to their own lineage and to that of their mother. Age-sets form bonds among groups of men close in age. (Clan leaders establish a new age-set (consisting of people of similar age) about every twentyfive years.) Members of an age-set are generally obligated to maintain ties of friendship and assist each other when in need.

Most Karimojong resisted government pressures to abandon their herding life-styles, but officials estimated that as many as 20 percent of the population may have died in the drought and famine that swept through much of the African Sahel in the early 1980s. British control of the region was fairly ineffective well into the twentieth century, although successful trading centers had been established as early as 1890. Traders brought ivory and, occasionally, cattle to augment local herds, and received grain, spears, and other metal products in return.

Karimojong, Jie, and Dodoth oral historians have recounted their forebears' arrival in the region from the north. Several small ethnic groups live among the Karimojong peoples in the far northeast:

The Dodoth people were believed to have separated from the Karimojong proper in the mid-eighteenth century. They migrated northward into more mountainous territory. Dodoth homesteads were generally in valleys, with dry season pastures on nearby hillsides. As a result, they did not practice the transhuman migration patterns that required other Karimojong peoples to establish dry-season cattle camps. The homesteads are larger than those of the Karimojong proper and more isolated from one another. Surrounding the homestead, upright poles are thrust into the earth, intertwined with branches and packed with mud and cow dung, forming a sturdy wall with only one or two small openings to the outside. As many as forty people often live in one homestead. Each wife has her own hut and hearth, and often keeps a small garden near her hut, but fields and pastures are outside the homestead. Adolescent girls often build huts of their own next to their mothers' huts. Adolescent boys also build a larger "men's house," where they live before marriage. People keep cattle and other animals inside the fortified wall at night. The Oropom clan, who were forced to move southward, live among tribes like the Karimojong as an apparent remnant of this society.

The Jie people, patrilineages maintaining the belief that they are distantly related, often keep homesteads near one another, but this practice is less common among other Karimojong. The clan comprises related lineages, often numbering over 100 people. Jie clans are exogamous, meaning that two people of the same clan cannot marry one another. In addition, men generally avoid marriage with a woman of their mother's clan or that of her close relatives. Jie clan members share some symbolic recognition of their common identity, such as jewelry, but they do not observe the ritual taboos of animals or foods that are characteristic of many other African clan.

The Labwor people, who live on the border between Acholi and Karamoja land, are historically and linguistically related to the Karimojong but have adopted much of the lifestyle of the Acholi. The Labwor region is also a center of trade between cultivators to the west and pastoralists to the east. The local economy centers on crops – chiefly sorghum, eleusine, maize, gourds, sweet potatoes, beans, and peanuts – but people also raise cattle and goats. A small number of men from Labwor have achieved substantial wealth as itinerant traders in northeastern Uganda. Labwor society is organized into homesteads centered on the core of patrilineally related men and their wives and children. In addition, age-sets are important stabilizing factors, forming crosscutting ties among lineages.

The Teuso people, who relied on hunting and cattle-raiding for much of their subsistence; but some have also gained a reputation as spies and informers in the local system of raiding and warfare. One such group was moved from their homeland in the 1960s to clear land for Kidepo National Park. Most of their Karimojong neighbors despised the Teuso so much so that people were willing to see them starve rather than allow them to join nearby villages. Some Teuso died, and others left the area to become low-wage earners in nearby towns. The social system that developed in response to depopulation and deprivation emphasized individual survival at the expense of other people.

The Tepeth people lived among the Karimojong, although they were usually classified as a separate Eastern Nilotic-speaking group. Oral histories relate that they were forced by government edict to vacate their homes in caves high in the mountains in northeastern Uganda. The move increased their vulnerability to be attacked by people and disease, and an influx of refugees from Sudan further disrupted life. Warfare and conflict increased, and the Tepeth developed a variety of religious cults and rituals to maintain their cultural integrity in the face of Karimojong and Sudanese influence.

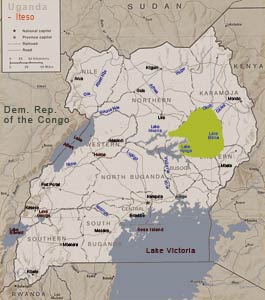

- The Iteso people

The social system was centred around the clan, and they shared similar cultural elements with neighbouring tribes like the Langi and the Karimojong. They were also influenced by their neighbours, the Bantu, particularly the Basoga people.

Previously, parents could arrange marriages for their children even without their knowledge and consent. However, the boy could directly consult the girl. Arrangements for the payment of bridewealth would be made. Then a traditional wedding ceremony would follow. There were three types of birth among the tribe: the single child, twins and the spiritual birth. The spiritual birth was said to be in the form of air or water. It was believed that such a child would often manifest itself in a home in the form of a cat or some other animal. There was no particular formal practice for the naming of children. A child could be named according to the circumstances in which it was born. The newborn baby would be initiated into the clan by conducting a ritual ceremony called etale. Another ceremony acquired a spiritual aspect because it was believed that failure to accomplish it would malign and weaken the child, thereby rendering it vulnerable to the wiles of evil deers. Among the Iteso a child belonged to the whole clan and not to a particular family. The main food consisted of millet, not mixed with cassava, and unsalted peas with groundnut paste and oil. Besides, people would also eat akobokob (cucumber) and simsim paste (sesame oil). The use of pots was prohibited, so also the use of tubes for drinking ajon (millet beer). They have had a variety of other foods such as, for example, pumpkins, wild berries, beans, meat of both domestic and wild animals, milk, butter and fish. The men did not eat together with women.

Married women used to wear barkcloth (bark from the tree – mutuba). They were responsible for the daily objects of utility in the household such as baskets, gourds, calabashes, winnowing trays, grinding stones, pots, brooms, pestles and mortars, ekigo (ladle for stirring millet) and eitereria (the fishing basket). The men were in charge of weapons and tools like spears, shields, arrows, bows, axes for cultivating the fields and the music instruments.

| Dances | |

| - Toto idwe (mother of many). Whenever a mother gave birth to twins, a special type of drum was beaten and the people would gather and dance, accompanied by a lot of eating and drinking. |

|

|

Akembe - Organised by boys who would invite girls to join their future spouses. |

|

| - Special dances to invoke the ancestors. In the process, some people would become possessed and start to communicate in the voice of the ancestors. This dance involved the shaking of rattles. |

|

| - Many other dances were, in general, performed at marriage ceremonies (airukorin), beer parties, meetings and other merry occasions. In this dance more instruments are used, including emudiri, entongoli (endongo - bowl lyre), adigirgi (endingidi - tube fiddle), akogo (thumb piano), amagarit and akaduumi (small drums). |

They did not regard death as a normal consequence. Death was attributed to ancestral spirits and witchcraft. As soon as a person had died, a witch doctor would be consulted to diagnose the cause of the death. The corpse was washed in the courtyard and wrapped in abangut (barkcloth), and then it was buried. It was customary to bury corpses with certain objects such as needles or razor blades to protect them against cannibals who might use their black magic to extract the corpes from the graves. If the corpse had been furnished with a needle, for example, it would reply that it was still busy mending its clothes and thus refuse to come out of the grave when invoked by a cannibal.

They believed in a supreme being called Edeke. They were much more involved with ancestral spirits which were believed to cause illness or bad luck if not well attended to. Every family possessed an ancestral shrine where libations were often poured or placed to placate the ancestors. They were a superstitious society, and they believed in witchcraft and wizardry. It was taboo for women to eat chicken. Some clans had specific taboos. The Iteso were not allowed to eat some animals; for example the bush-buck (ederet) was taboo to a number of clans.

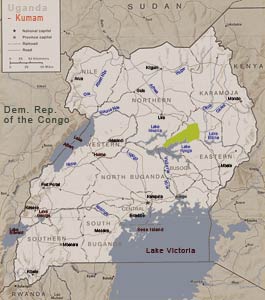

- The Kumam people

Normally the parents would arrange marriages for their children. Girls of minor age were chosen for a marriage to be performed later on. In effect, the young girl would become the wife of the respective boy but she would wait to be officially handed over to him when she had reached the proper age for marriage. In some cases, the young girls, as was made the decision, had to grow up in the home of their future husbands, and hence they were raised by the families of their husbands-to-be. When she reached the proper age for marriage, a ceremony would be organised to formalise the relationship and the bridewealth. Whenever a woman was pregnant, she was not supposed to eat the intestines of any animal. After giving birth, a feast was organised. If the new-born child was a boy, he was given a spear; if the baby was a girl, she was presented with a calabash. This ritual is said to protect the child against bad omens. The name given to the child would reflect the experiences made in the course of the birth. Twins were considered good. Then special rituals were performed, and a lot of eating and dancing was performed. The ritual ceremony was intended to introduce the child into the society.

They do not believe in such a thing as natural death. Every death was attributed to witchcraft. When a person died, there was a lot of weeping and willing. Burial would wait until all the relatives of the deceased had gathered. Mourning could go on for a week. As it seems, they did not believe in eternal life but rather were convinced that the spirits of the dead did not die. They had the power to inflict harm on the living. For this reason, the family had a shrine for the ancestral spirits. Here they were laid and rested during their wanderings and visits to the family. In the event of sickness or before going on a hunt or a long journey, one would pass by his ancestors‘ shrine to ask for health and good fortune.

The Kumam were originally pastoralists, they lived on cattle and sheep breeding, had goats and chickens. Today they also live on agriculture, their staple food being millet, sorghum, potatoes, beans and peas served with sauces. The land was communally owned by the clan. The women made pots, plates made from clay as well as a variety of baskets and mats.

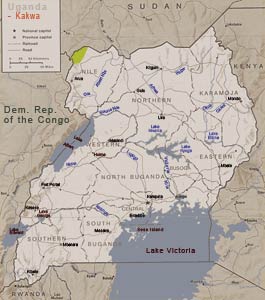

- The Kakwa people

- The other theory states that the Kawka were originally known as Kui, and the Kui were said to have been fierce fighters who inflicted heavy losses on their enemies. For this reason, the Kui are said to have nicknamed themselves Kakwa because their fierce attacks were like the bite of a tooth.

- All the Kakwa clans in the region of Kobuko, a part of Maracha and Aringa, state that their origin is Loloyi, but none of them can tell what exactly Loloyi means or where it io be found.

Through the linguistic connection, the Kakwa can be traced back to the Bari dialect of the southern Sudan. The Kobuko tradition claims that the first Kakwa ancestors came from the direction of Ethiopia. The general conjecture is that they had split before they came into the Bari region, an eastern Nile group; furthermore, that the Ugandan people gave them the name the Plain Nilotes, similar to the groups of the Iteso and the Karimojong. They might have separated from the Bari in Kapoeta.

Kakwa Mythology of Creation

Their great-great-grandfather was Mungura, and his wife was called Muri. Together, they created the first living beings: wild animals and domestic animals, etc. Mungura and Muri became parents of twins: this was, however, considered a bad omen at that time, and hence the children were handed over to a certain Jongbo, who ws tas told to throw the children away into the bush. Jongbo, however, realised that these were the twins who would one day be our fathers. So, he hid the children at his home and nurtured them there until they had grown up.

Their institutions were segmentary, they had no centralised system. The clan was the basic unit of social and political life. Each clan was independent from the others, and it enjoyed sufficient traditional loyalty. The head of each clan was the chief, known as the Matter or Buratyo. The chief was both a political figure and the rainmaker. The society was matrilineal, and the position of the chief was hereditary. The heads of some subclans were brothers or uncles.The Kakwa did not have a real class system, but merely distinguished between upper and lower people. The lower comprised the house servants, cattle herders and young children. The economy was based on the cultivation of corn, millet (sorghum), maize, cassava, beans (burusu), sweet potatoes and potatoes (they called them „pawpaws“, Irish potatoes). Some families also practised mixed farming. They kept cattle, goats and sheep and established agriculture. Livestock was mostly seen as a socio-economic and financial investment. Notably, livestock was exchanged as gifts in marriages and other social functions, or it was sacrificed in celebrations, and at the occasion of funerals; and whenever it was necessary, they sold it for cash. The men work in the field, cattle the herds and repair the houses. Women have to remove the rubbish from the cultivated fields, furthermore they weed, harvest the crops and make salt. Salt was made from plants known as morobu and bukuli. They were more engaged in handicraft like basket weaving and pottery. The Nyangilia clan was specialised in iron smelting, making spears, knives, hoes and a variety of other iron implements.

- The Bari of the Nile are sedentary agro-pastoralists. They exploit the Savannah lands along the river Nile. The economy is based on subsistence mixed farming; their domestic livestock (small and large) is mainly raised for the provision of food.

Traditionally, the Bari believe in one almighty god and the existence of powerful spirits (good and evil). In the past, it was custom among the Bari to undergo initiation ceremonies. Both boys and girls subjected themselves to the removal of their lower front teeth. The girls, in addition, got tattoos: around the belly area, the flank, the back, and the face. On the temple, they have used the form of arrow shapes or simple flowers.

If a member of the upper class assumed chieftainship, he had to perform some form of a traditional ritual. During the installation of the chief, all the clan members would gather at the new chief's house known as Kadina Mata. They would bring food and beer. The elders would sit alone and invoke the ancestral blessings to enable the new chief to lead his people in peace and prosperity. Afterwards followed the party with dancing and rejoicing. The chief had to protect the hunting grounds and to give advice. When he was spiritual, this is in the power of the spirits, he arranged the ceremony for rainmaking and performed fertility rites. Normally he acted as adviser to the council of elders. Disputes were settled by the clan elders. The most serious of the cases would be referred to the chief. Women and children would not participate in passing judgement. They had to sit down and be quiet. There was no time for judging a thief, as they would be killed „in a manner foxes are killed“, something similar to a „mob justice“. Such a case would often bring about warfare between clans. Normally the thief had to pay a cow, a goat, etc. as compensation. A chief had no standing army. Each chieftainship, however, had a military leader known as the Jokwe. Before mobilising for war, the chief and the Jokwe would consult the elders, and a ritual ceremony would be performed in order to seek communication from the clan‘s ancestors about the military strengh of the enemy clan. Among the Leiko, the women would accompany their husbands to war. If a man killed a woman during war, the ancestors would be certain to disapprove, and this man would fall victim much earlier.

War (intertribal or in the case of resisting foreigners) is not alien to Bari history. In general, the Bari have co-existed well with the neighbouring ethnic groups, but they have also had to pick up arms to defend their land against slave traders and plundering warriors. There is documentation of Bari resistance against the invasion by the Dinka* and Azande** (Zande), as well as of numerous encounters with Turkish slave traders.

- *The Dinka are a Black African people in the Sudan settling in the wet savannahs of the federal states of Gharb Bahr al Ghazal in the west and Western Equatoria in the south, parts of southern Kurdufan and the expansive fenlands of the Sudd of the Jonglei province and the province Upper Nile in the east up to the Ethiopian frontier.

- **The Azande (also Zande). They settle mainly in the northern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (province Upper Zaire), in the southwestern area of the Sudan and the southeastern part of the Central African Republic (districts of Rafaï, Zémio und Obo). The Azande, up to the colonial period, had established a compact tribal union, with the individual chieftainships not subjecting themselves to a central leadership according to the example given by the neighbouring tribes of the Dinka or Nuer.

The Bari have been consistently under pressure: nowadays, from modern urbanization annexing their green lands and infusing different cultures into their lifestyles; and historically, the Baris were devastated by slave traders and forced by Belgians (especially from the Lado enclave) into labor camps and used as porters to carry ivory tusks to the Atlantic coast. The two Sudanese Civil Wars also affected the Bari in regard to its social, economic and financial dynamics. The former Ugandan dictator, Idi Amin was born into the Kakwa ethnic group. After Amin was disposed of in 1979, many Kakwa people were killed in revenge killings, causing many to leave the area.

More information about Peoples and Cultures of Uganda you will find in the Book

"Peoples and Cultures of Uganda" from Richard Nzita & Mbaga Niwampa

- published 1998 by Fountain Publishers, Kampala - Uganda

back to the Index – Projects Uganda |

Text by Sarah Ndagire and Albi - Revised by Hermelinde Steiner